The Polar Museum tested out co-curation for their recent exhibition – the varied team ensured that a wide cast of characters made an appearance in ‘The Year That Made Antarctica’.

There’s just one month left to run of our current exhibition at the Polar Museum: The Year That Made Antarctica – People, Politics and the International Geophysical Year (IGY). Set against the backdrop of the Cold War, the exhibition explores the diplomatic and logistical challenges of setting up a science programme in one of the World’s most remote places. The year not only produced scientific results that are still important for us today as we study our changing planet, it also broke new ground in establishing the entire Antarctic continent as a place reserved for peaceful and scientific activity.

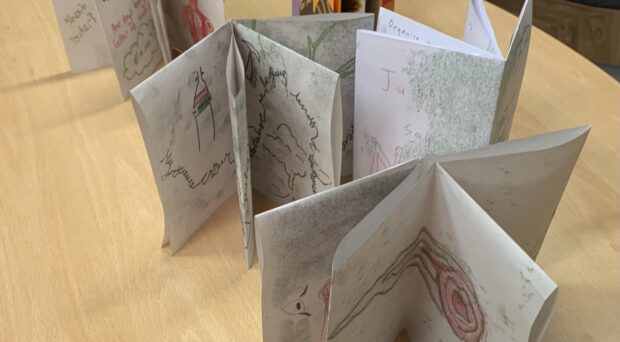

The exhibition also broke new ground for the Polar Museum’s team. We chose to use the exhibition as a pilot for a new way of working in the museum. The exhibition was co-curated with some of our fellow staff in the Scott Polar Research Institute, museum volunteers and students from the Department of History and Philosophy of Science. We split the project into two parts – we met weekly and for the first eight weeks we formed a research group, working through book chapters together, looking at objects in the collections, and listening to guest speakers. Then, with our newly developed expertise, we came back together to produce the exhibition.

I’ve worked on co-curation projects in the past, and have seen first-hand how different groups of curators breathe new life into content, and shift the focus to sometimes surprising places. An exhibition about the IGY was only ever going to be a partial telling of the history. With only around 20 objects, 10 large images and a few hundred words of text we wanted to tell the story of the biggest science Olympics the world has ever seen, where 1000s of professional and amateur scientists from more than 60 countries came together to study 11 different scientific topics. Over those eight weeks we were reminded that often the hardest part of an exhibition curator’s job is not deciding which brilliant facts, objects or artworks to include – but which ones to exclude. There’s rarely space for everything.

We needed a way to help us make our decisions. Our co-curators looked at the audiences we’re working especially hard to reach in the Polar Museum at the moment. After much discussion, they decided that the exhibition should be accessible to women, as our audience research shows that they are underrepresented in our visitors (perhaps because many stories of polar exploration are about heroic men and acts of derring-do, while the women in the stories often take a back seat). To achieve that, where women were part of the story we agreed they should be prominent in our telling of it. They also agreed that, where possible, a local story should be promoted because our audience research shows that we have lower numbers of local visitors than many of the other Cambridge museums.

Having decided on our audience, we decided that the best way to share the story with them was to frame the exhibition around a wide range of people, rather than around chronology, scientific achievements or political moments. Those aspects of the story are still woven in there, but we always started each part of the exhibition with a person. Dr Edna Plumstead helped us to understand the importance of the Commonwealth Transantarctic Expedition in establishing the theory of continental drift. This is in contrast to the more usual story of that expedition, which focuses on the incredible bravery and contrasting personalities of Vivian Fuchs and Edmund Hillary. Local Cambridge residents Bruce Elsmore and Alison Shwabe helped us to explore how people in Cambridge watched and listened to the satellite Sputnik, launched by the Soviet Union during the IGY. Most stories about Sputnik focus on the space race between America and the USSR, and forget that 1000s of amateur radio operators tuned in to hear its chirps as it passed by.

The path taken by our team of co-curators was one that celebrated a diverse cast of characters during the IGY. We didn’t focus on the big names, or the political players – instead we sought out a representative sample of people who experienced the year in a wide range of ways. Had I been left to my own devices, the exhibition would have been more representative of my own interests (I’m a massive science geek, so there would have been more technical diagrams!) The joy of working with a group, as we did, is that many more people are able to add their interests to the mix. The Year That Made Antarctica is a richer and more varied exhibition thanks to the broad range of interests and experiences of our co-curators. Now that we’ve tested the process out, we’ll definitely be co-producing more exhibitions at the Polar Museum.