Hide and Seek

Looking for Children in the Past

Children outnumbered adults for most of human history, yet they rarely appear in the stories that museums tell. A past without children is incomplete.

This virtual exhibition, based on the physical display at MAA from 30 January 2016 - 29 January 2017, aims to redress the balance.

Some objects will be familiar: a doll, a sledge, a baby's feeding bottle. Other artefacts won't look like children's objects: pots with small fingerprints, a tiny handaxe made 400,000 years ago, goldwork as fine as human hair. By looking carefully at all of this evidence, we will find out about children's lives.

We invite you to look closely to seek glimpses of children's lives in East Anglia and across England from 1 million years ago to the 20th century.

To read more about the process of putting together the exhibition, the first museum exhibition of its kind dedicated to the archaeology of children, visit the Archaeology of Childhood Project blog.

How do we find out about children in the past?

Where we don't have children's footprints, archaeologists look to artefacts to build a picture of children's lives. In the past, some objects were overlooked because they don't obviously relate to children. Others were misidentified. This has resulted in an incomplete story.

To bring out the hidden stories of children, we are piecing together different sources of evidence and drawing comparisons with other cultures.

Hide and Seek: Looking for Children in the Past was a collaborative project between the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology and Cambridgeshire County Council, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Footprints from the Past

We start with the earliest evidence we have of children in the archaeological record - footprints from the distant past.

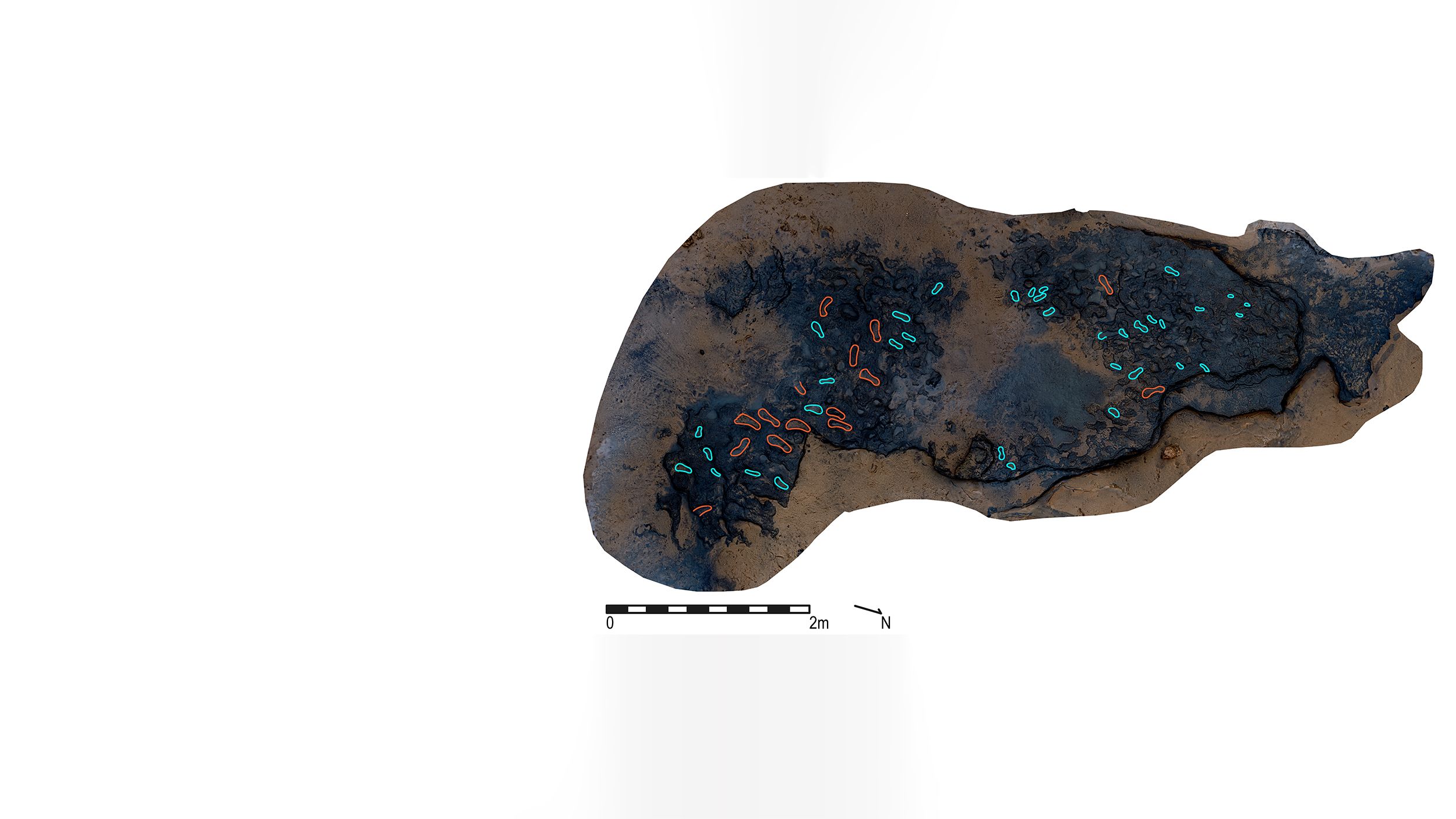

Happisburgh footprints

Happisburgh Footprint Project

Early Pleistocene, 780,000 - 1 million years ago

In May 2013, fierce storms on the Norfolk coast uncovered footprints left by children and adults as they walked along the mudflats of a long-gone river. They were made 780,000 to 1,000,000 years ago by a human-like species (Homo antecessor), and are the oldest of their kind outside of Africa.

Was the group on the lookout for food? What role did the children play in these activities? The footprints, sadly, are silent on these questions.

Roman roof tile

Wendlebury, Oxfordshire. Roman, 1st - 2nd century CE

Kind permission of Wendlebury Gate Stables, Network Rail and Chiltern Railways, OXCMS:2014.90

About 2,000 years ago, a Roman toddler stepped on a still-drying roof tile, leaving behind a chubby footprint. Roof tiles were produced in batches, laid out to dry and then fired.

It is possible to imagine a toddler running along a row of drying tiles quite delighted with the trail of footprints they had left behind. Did children help make the tiles - perhaps to the regret of the adults?

Comparisons and Replicas

These artefacts, usually made of pig bones, are found throughout England. Their function was debated for decades. Drawing on historic evidence in Shetland, where children threaded and spun identical bones to create a buzzing sound, archaeologists were recently able to show that the ancient bones were used for the same purpose.

Play the video below to hear how they would have sounded!

Modern buzz-bone made of a pig's foot bone. 2015. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire. Made by Dr Elizabeth Blake

Modern buzz-bone made of a pig's foot bone. 2015. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire. Made by Dr Elizabeth Blake

Buzz-bone made of a pig's foot bone. Late 11th or early 12th century. St Martin-at-Palace Plain, Norwich. Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NWHCM:1985.444.930

Buzz-bone made of a pig's foot bone. Late 11th or early 12th century. St Martin-at-Palace Plain, Norwich. Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NWHCM:1985.444.930

Buzz-bone made of a pig's foot bone. Early 16th century. Pottergate, Norwich. Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NWHCM:1974.101.2278

Buzz-bone made of a pig's foot bone. Early 16th century. Pottergate, Norwich. Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NWHCM:1974.101.2278

Illuminating Illustrations

This fourteenth century illustration from an illuminated manuscript shows two children enjoying recognisable winter pastimes: skating and sledging. The only significant difference is that the sledge and skates are made from horse bone.

Illuminating Illustrations

Sledge made of a horse’s jaw. The Perspex sheet shows where the seat would have been. 16th - 18th century. Castle Mall, Norwich. Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NWHCM:2011.26.A1

Sledge made of a horse’s jaw. The Perspex sheet shows where the seat would have been. 16th - 18th century. Castle Mall, Norwich. Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NWHCM:2011.26.A1

Sledge

Illustrations like the one above allowed Norfolk archaeologists to identify that this horse’s jaw was used as a child’s sledge. The underside of the bones have been worn smooth from being pulled over rough surfaces. A wooden platform was used for a seat.

Skates made of horse’s leg bone. Medieval or later. Bread Street and Fenchurch Street, London. MAA, 1883.833 and Z 40671

Skates made of horse’s leg bone. Medieval or later. Bread Street and Fenchurch Street, London. MAA, 1883.833 and Z 40671

Skates

Bone ice skates were used in England from the eighth to the early twentieth century. Skaters stood on the bones and propelled themselves forward using an iron-tipped pole.

Miniature handaxe made of flint (front). Lower Palaeolithic, c. 425,000 years ago. Foxhall Road, Ipswich. Ipswich Borough Council (Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service), IPSMG: R.1920-76.182

Miniature handaxe made of flint (front). Lower Palaeolithic, c. 425,000 years ago. Foxhall Road, Ipswich. Ipswich Borough Council (Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service), IPSMG: R.1920-76.182

Miniature handaxe made of flint (back). Lower Palaeolithic, c. 425,000 years ago. Foxhall Road, Ipswich. Ipswich Borough Council (Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service), IPSMG: R.1920-76.182

Miniature handaxe made of flint (back). Lower Palaeolithic, c. 425,000 years ago. Foxhall Road, Ipswich. Ipswich Borough Council (Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service), IPSMG: R.1920-76.182

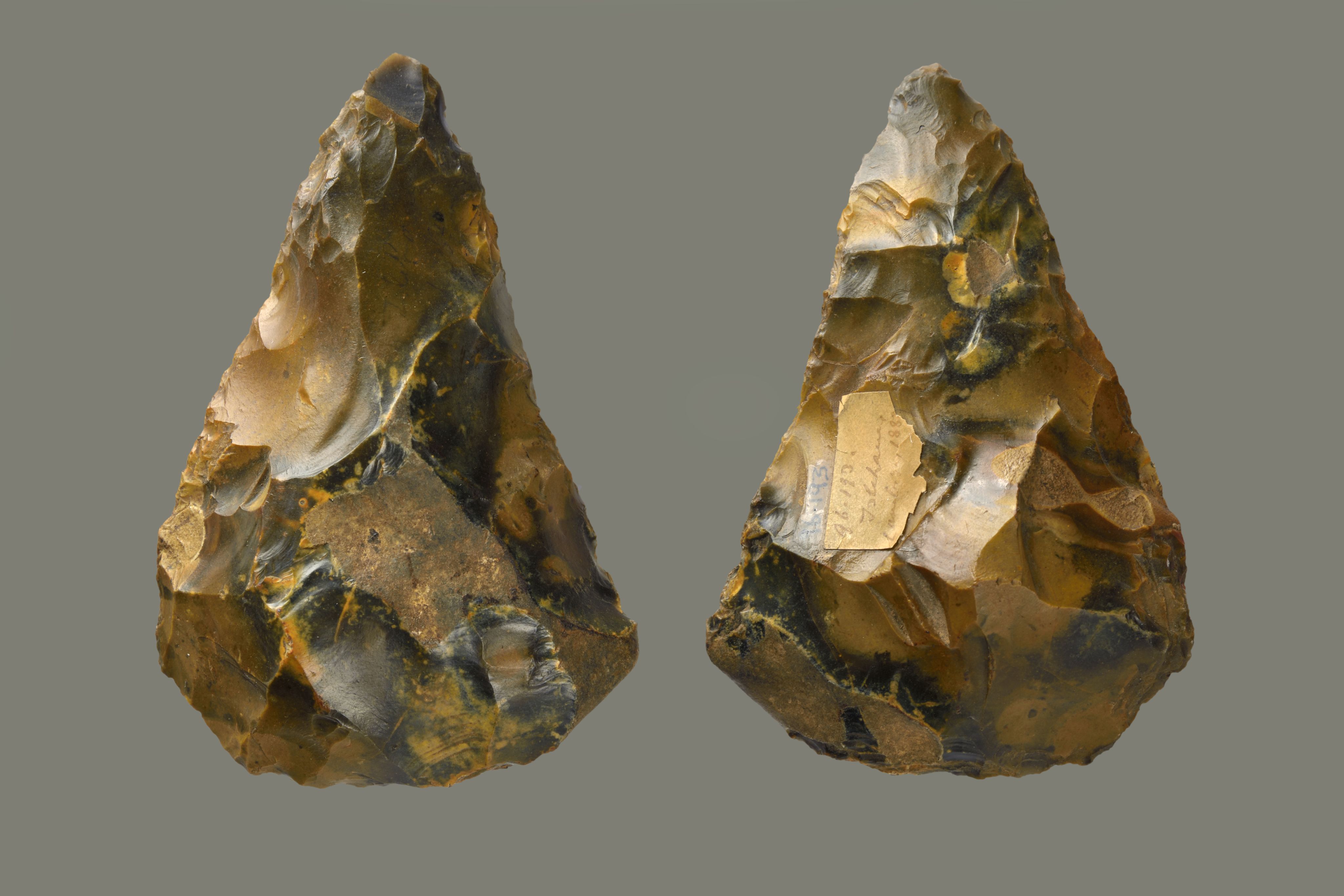

Handaxe made of flint. Lower Palaeolithic (500,000 - 150,000 years ago). Isleham, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1896.193/Record 2

Handaxe made of flint. Lower Palaeolithic (500,000 - 150,000 years ago). Isleham, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1896.193/Record 2

What About Size?

When archaeologists find miniature artefacts, the temptation is to explain away their small size. In the case of a tiny handaxe such as this, the usual interpretation was that it was originally much larger but was worn down by use and re-sharpening. But this would result in an irregularly shaped handaxe, whilst this example is symmetrical.

The explanation could be much simpler. Handaxes were multipurpose tools and learning to use them was a critical skill for children to acquire. This miniature version would have fitted into a child's hand, and allowed them to learn through play.

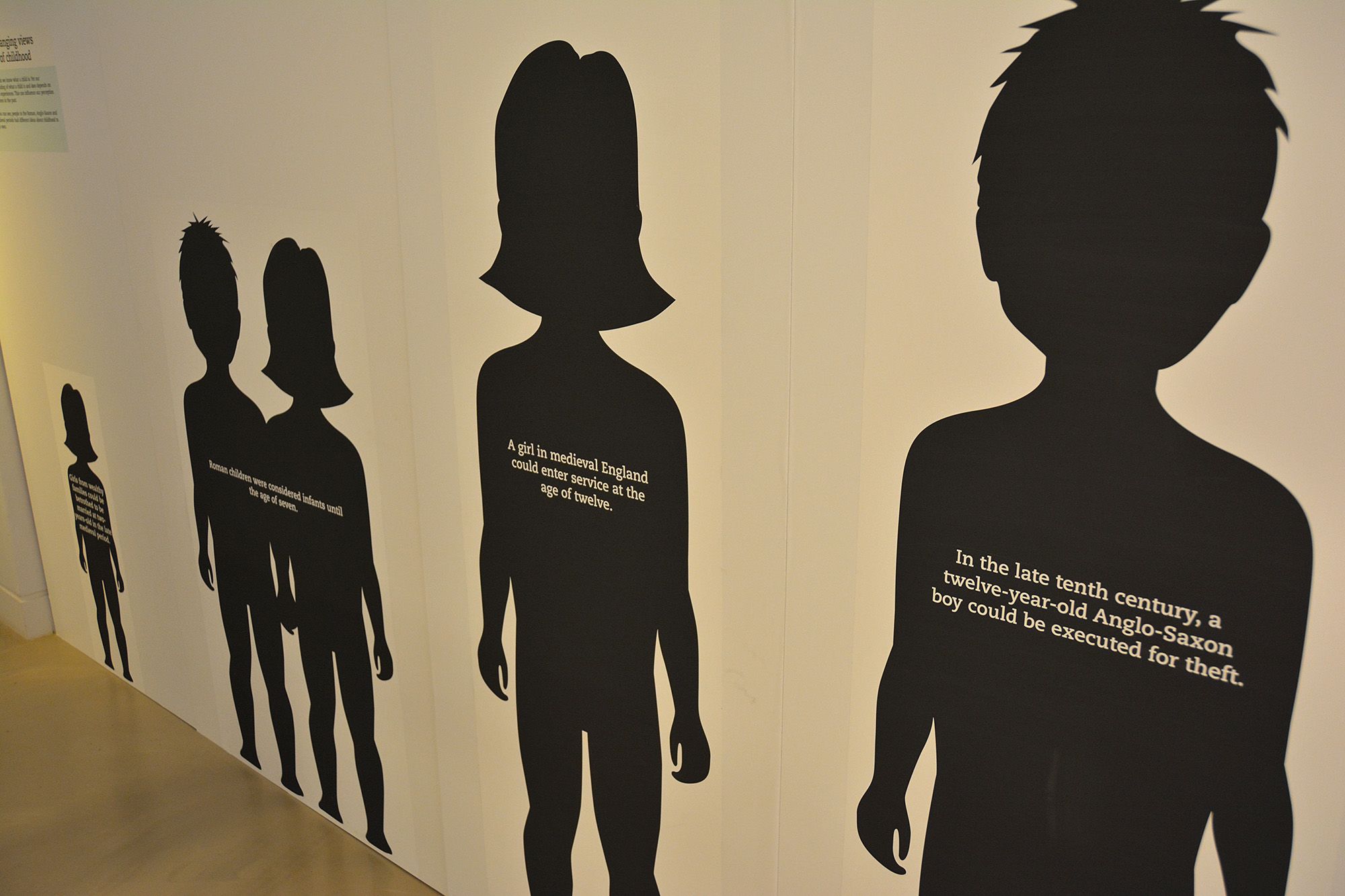

Changing views of childhood

"I know a lot about children - I used to be one."

We all think we know what a child is. Yet our understanding of what a child is and does depends on our own experiences. This can influence our perception of children in the past.

As you can see, people in the Roman, Anglo-Saxon and Medieval periods had different ideas about childhood to our own.

Did you know?

- Girls from wealthy families could be betrothed to be married at two-years-old in the late medieval period.

- Roman children were considered infants until the age of seven.

- A girl in medieval England could enter service at the age of twelve.

- In the late tenth century, a twelve-year-old Anglo-Saxon boy could be executed for theft.

Gallery installation view

Gallery installation view

Dressed to Impress?

Our understanding of what children wore in the past comes from depictions in art, written descriptions and surviving clothing. This can result in a distorted picture, as unusual or special clothing particularly of the rich was more likely to be recorded or preserved.

Whilst some children’s clothes from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries look like those of a miniature adult, these were probably for ‘Sunday best’. Everyday wear, such as the clogs, was plainer and better adapted to the active lifestyles of children.

In this print, the boy and girl have exchanged parts of their outfits. The boy is wearing her collar and cap and holds her fan. She wears his jacket and hat and holds his sword. Boy and Girl, John Faber II, 1744. Lent by the Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, P.83-1953.

In this print, the boy and girl have exchanged parts of their outfits. The boy is wearing her collar and cap and holds her fan. She wears his jacket and hat and holds his sword. Boy and Girl, John Faber II, 1744. Lent by the Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, P.83-1953.

A small linen coat for a child, made from Indian chintz. During the eighteenth century, middle and upper class men wore full-sized versions during mornings spent in their library. 1750 - 1775, England. St Edmunsbury Heritage Service, BSEMS:1976.47

A small linen coat for a child, made from Indian chintz. During the eighteenth century, middle and upper class men wore full-sized versions during mornings spent in their library. 1750 - 1775, England. St Edmunsbury Heritage Service, BSEMS:1976.47

Painted on this Delftware mug is an image of a father holding the hand of his younger daughter. At the top is written: 'Mary Turner Aged 2 years 14 days Sep.2 1752'. Could this be the date of her baptism, or perhaps the day she died? 1752, London or Bristol. Lent by the Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, C.1583-1928

Painted on this Delftware mug is an image of a father holding the hand of his younger daughter. At the top is written: 'Mary Turner Aged 2 years 14 days Sep.2 1752'. Could this be the date of her baptism, or perhaps the day she died? 1752, London or Bristol. Lent by the Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, C.1583-1928

Clogs were common throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly in the north and west of Britain. Children and adults wore them as protective footwear in breweries, laundries, mines, and for farming. Late 19th century, Lancashire or Yorkshire. MAA, 1914.407 A-B

Clogs were common throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly in the north and west of Britain. Children and adults wore them as protective footwear in breweries, laundries, mines, and for farming. Late 19th century, Lancashire or Yorkshire. MAA, 1914.407 A-B

What Would Survive?

Children's toys are often made of materials that do not survive well in the ground. But even with only part of an object we can still learn a great deal.

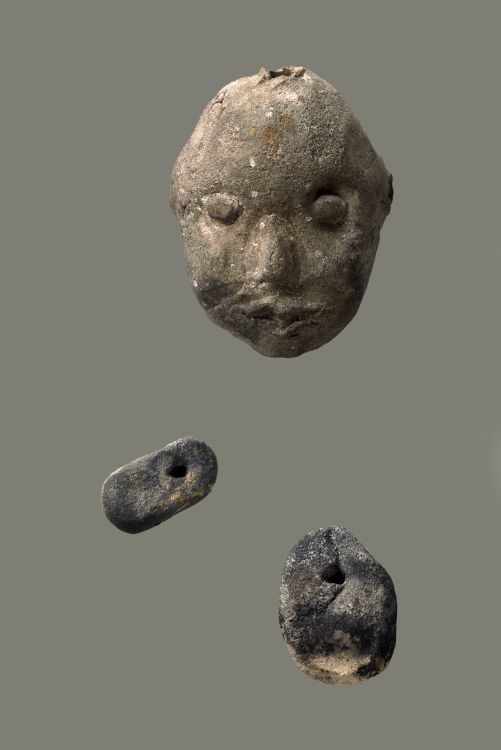

Puppet

Only the head, one foot and one hand remains of this medieval puppet. The body and limbs were probably made of organic material, such as wood, that did not survive. The holes through the head, hand and foot show it was a puppet.

Eventually the body of this modern doll may also decay. What could future archaeologists tell from looking at what remains?

Head, hand and foot of a puppet. Medieval (AD 1066 - 1550). Wimblington, Cambridgeshire. Chatteris Museum, CHSCM:1970.2

Head, hand and foot of a puppet. Medieval (AD 1066 - 1550). Wimblington, Cambridgeshire. Chatteris Museum, CHSCM:1970.2

Modern doll with a ceramic face and a fabric body. 20th century. England. On loan from a private collector

Modern doll with a ceramic face and a fabric body. 20th century. England. On loan from a private collector

Rattle

This rattle was woven from reeds using a technique that is at least several hundred years old. Before the rattle was completed, two small metal loops were inserted inside to act as clappers.

Most people will immediately recognise this object and its connection with children. If the rattle was buried, however, over the years the wicker would decompose and only the metal clappers would survive. Archaeologists often discover unidentified metal fragments - how many of them were once rattle clappers or other types of object associated with children?

Rattle with metal clappers, woven from reeds. 20th century. Chatteris, Cambridgeshire. Chatteris Museum, CHSCM:1992.3301

Rattle with metal clappers, woven from reeds. 20th century. Chatteris, Cambridgeshire. Chatteris Museum, CHSCM:1992.3301

Behold the child, by nature's kindly law,

Pleased with a rattle, tickled with a straw.

A Laughing Child Holding a Wicker Rattle, Jan de Bray, mid-17th century. © Victoria & Albert Museum

A Laughing Child Holding a Wicker Rattle, Jan de Bray, mid-17th century. © Victoria & Albert Museum

Metal clappers, made for display. 2016. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire.

Metal clappers, made for display. 2016. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire.

Funerary monument

Medieval, c.1525

Aldenham, Hertfordshire

MAA Z 22616

Images of children in the past were created by adults. These did not always portray a true picture of children's lives. This memorial from a Hertfordshire church commemorates the death of an important lady. She is shown with her 12 children, four sons and eight daughters.

The children, sometimes called weepers, are in prayer for their mother. If you look carefully, the children are all very similar. An accurate representation of their appearance was less important than their large number, which reflected well on the mother for bringing so many children into the world.

Look. Look Again.

Toys and games can be as fleeting as childhood itself. Chalk lines marking out hopscotch are washed away by the rain, while metal cars rust and conkers rarely survive the autumn. Other toys, such as Lego blocks or a doll passed down through the generations, could survive decades or even centuries.

Which activities from your own childhood could future archaeologists identify?

Preserving Play

"I am called Childhood, in play is all my mind..."

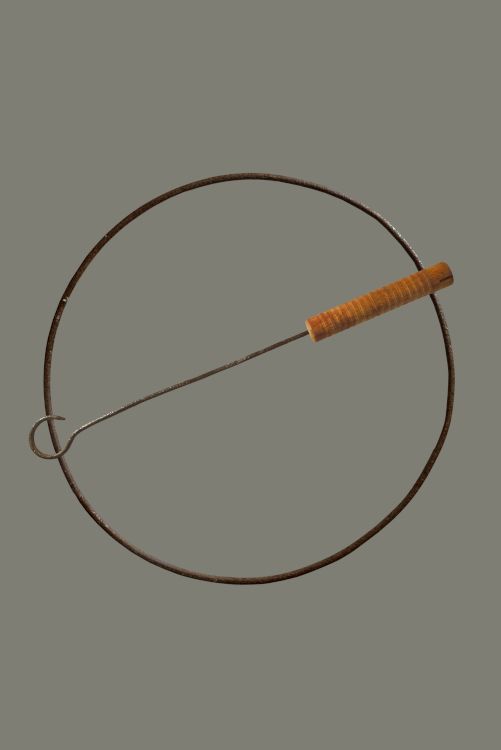

Many of the toys in this section, like the hoop and stick, are also shown in Pieter Bruegel's painting Children's Games (1560) seen below.

Toys can never provide a full picture of children's play. Games such as leapfrog or stick fights leave no trace. The toys in this case were made by adults. They are robust and so more likely to survive. Others were kept and saved by adults for sentimental reasons, sometimes for generations.

Have you saved any toys from your childhood?

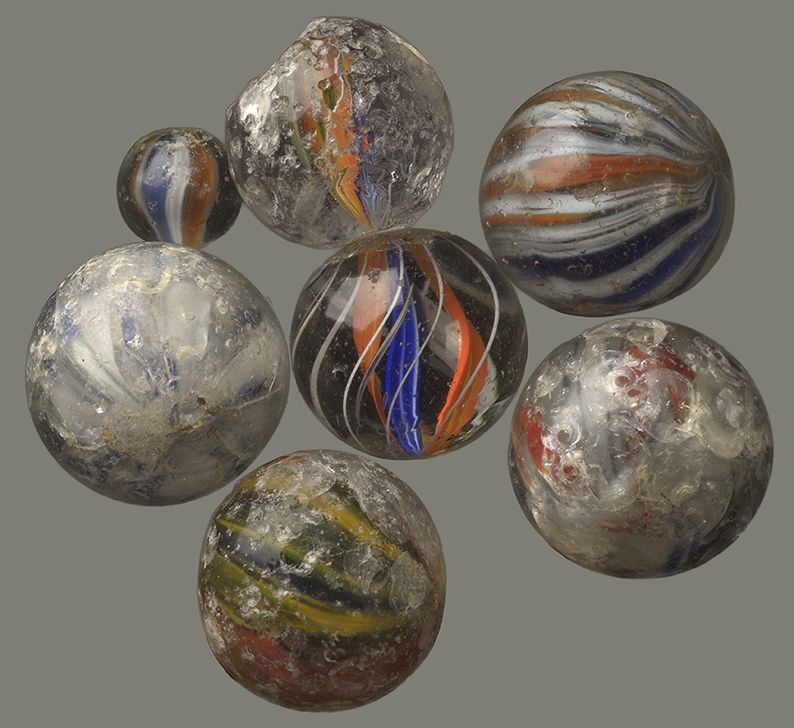

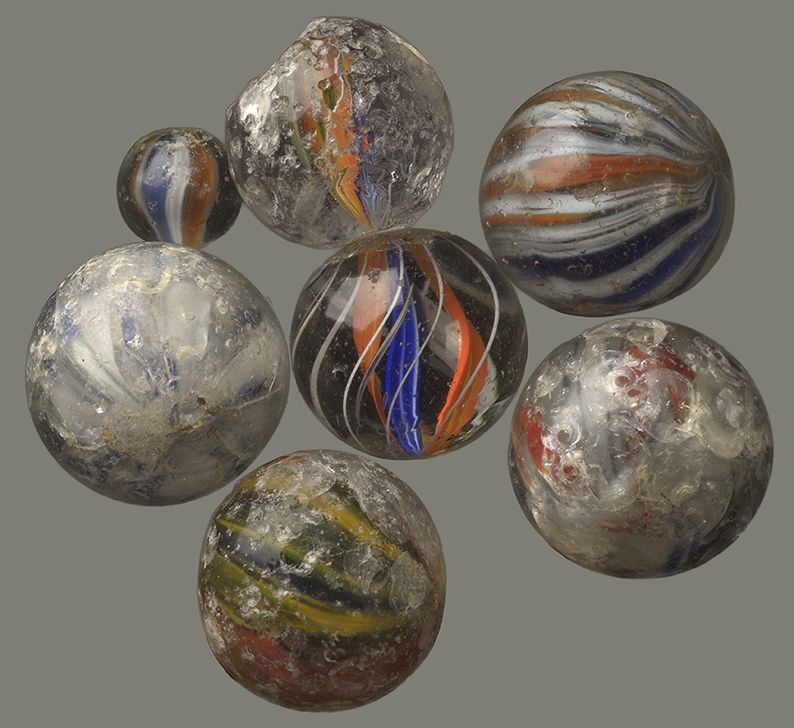

Seven marbles made from coloured glass. Marbles as we know them today came to Britain in the medieval period. Imported from the Low Countries, they have been used by children of all ages ever since. Probably early 20th century. Bridge Street, Peterborough. MAA 1974.291 A

Seven marbles made from coloured glass. Marbles as we know them today came to Britain in the medieval period. Imported from the Low Countries, they have been used by children of all ages ever since. Probably early 20th century. Bridge Street, Peterborough. MAA 1974.291 A

Children (and adults) have played with balls for thousands of years. Made from a variety of materials throughout history from textiles to rubber, these two leather balls were found in a wall cavity. White and brown leather balls. 17th-19th century. Botesdale, Suffolk. St Edmundsbury Heritage Service, BSEMS:1997.64.1-2

Children (and adults) have played with balls for thousands of years. Made from a variety of materials throughout history from textiles to rubber, these two leather balls were found in a wall cavity. White and brown leather balls. 17th-19th century. Botesdale, Suffolk. St Edmundsbury Heritage Service, BSEMS:1997.64.1-2

A clay doll torso and head. Dolls from the Roman period were usually made from clay and had jointed limbs allowing the arms and legs to move. Roman, late 2nd century CE. Petty Cury, Cambridge. MAA 1978.1

A clay doll torso and head. Dolls from the Roman period were usually made from clay and had jointed limbs allowing the arms and legs to move. Roman, late 2nd century CE. Petty Cury, Cambridge. MAA 1978.1

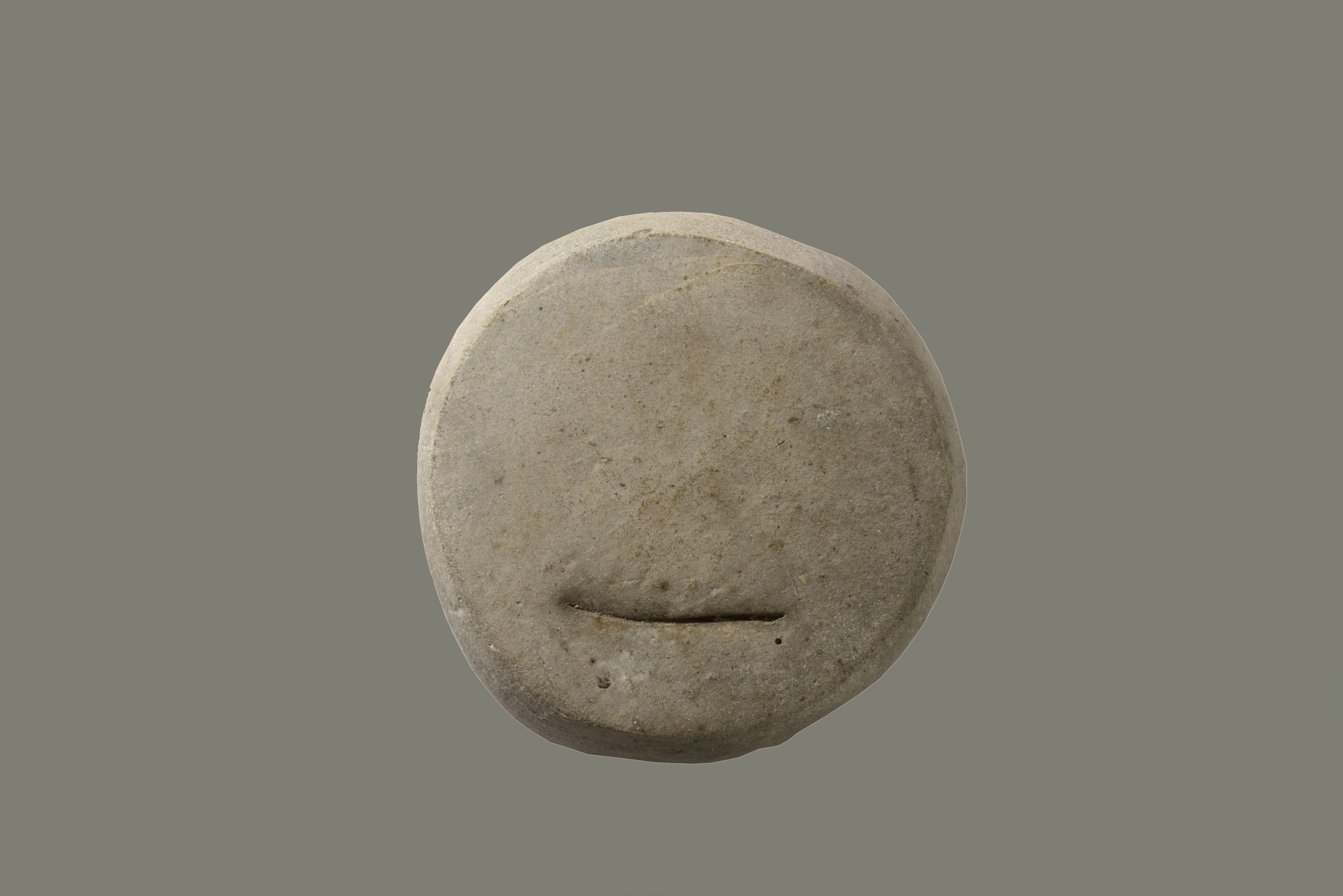

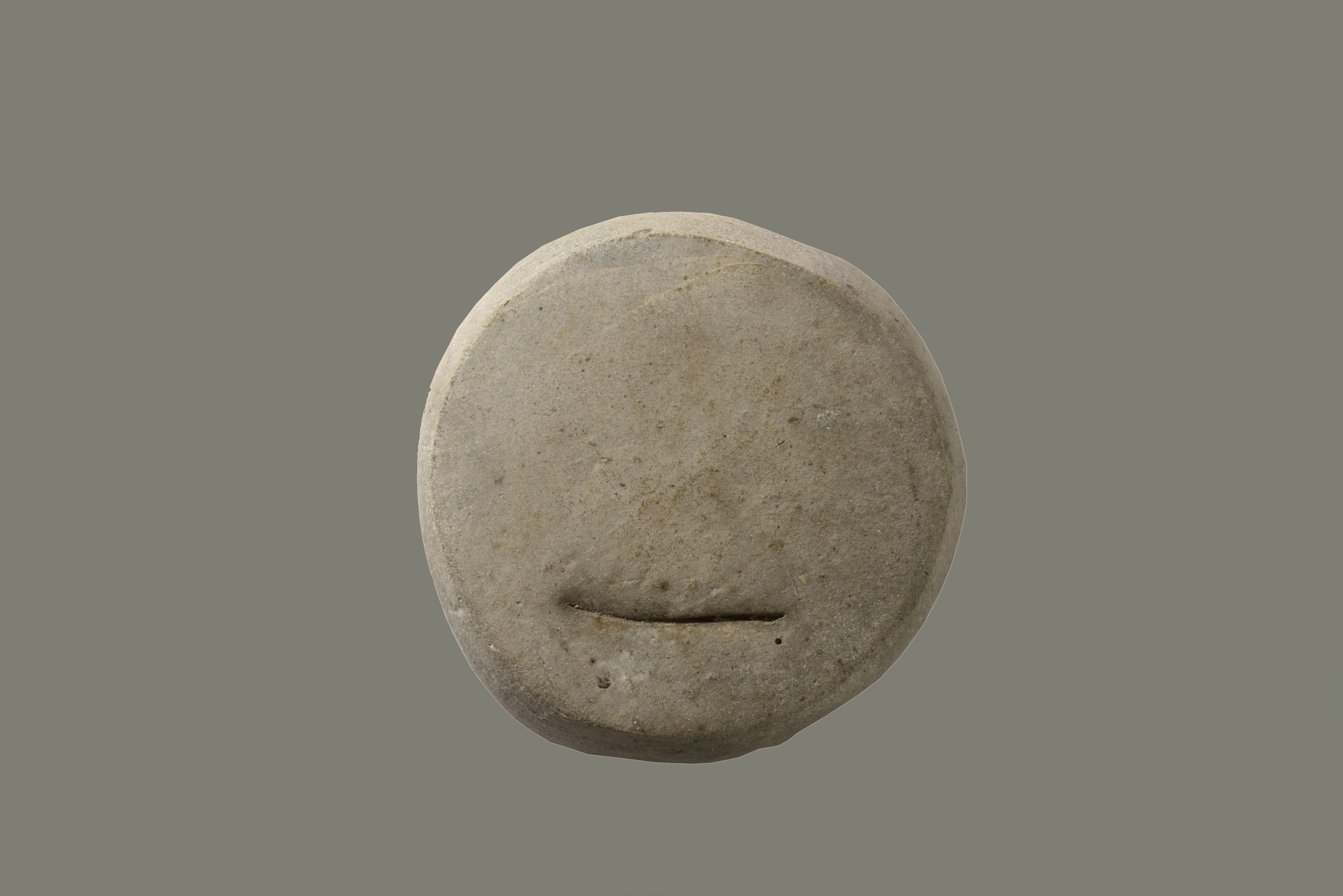

Cement mould. Materials used to make toys were in short supply during the First World War so children and manufacturers had to think more creatively when it came to toys and play. The Cambridge Cement Works gave out reject cement blocks like this one to children in place of toys, although we don't know what the children thought of them. c.1916. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK.TO778.81.2

Cement mould. Materials used to make toys were in short supply during the First World War so children and manufacturers had to think more creatively when it came to toys and play. The Cambridge Cement Works gave out reject cement blocks like this one to children in place of toys, although we don't know what the children thought of them. c.1916. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK.TO778.81.2

Brown glazed whistle in the form of an owl. Clay whistles were considered novelties or toys rather than serious musical instruments. Those in the shape of birds could produce a warbling sound when played by pouring a little water into the body. 17th - 19th century. Wilburton, Cambridgeshire. MAA Z 16456

Brown glazed whistle in the form of an owl. Clay whistles were considered novelties or toys rather than serious musical instruments. Those in the shape of birds could produce a warbling sound when played by pouring a little water into the body. 17th - 19th century. Wilburton, Cambridgeshire. MAA Z 16456

Green glazed whistle in the form of a cockerel. 15th - 17th century. Ely, Cambridgeshire. MAA 1910.366

Green glazed whistle in the form of a cockerel. 15th - 17th century. Ely, Cambridgeshire. MAA 1910.366

Green glazed whistle in the form of a ram. Clay whistles were considered novelties or toys rather than series musical instruments. 15th - 17th century. Lincoln, Lincolnshire. MAA 1929.467

Green glazed whistle in the form of a ram. Clay whistles were considered novelties or toys rather than series musical instruments. 15th - 17th century. Lincoln, Lincolnshire. MAA 1929.467

Tin toys. Tin was first used to make toys in the mid-nineteenth century. It was hardwearing and cheap to produce, making it ideal for mass production. 1930s-1950s. Chatteris, Cambridgeshire. Chatteris Museum, from the Neville Angell estate. CHSCM:2015.07

Tin toys. Tin was first used to make toys in the mid-nineteenth century. It was hardwearing and cheap to produce, making it ideal for mass production. 1930s-1950s. Chatteris, Cambridgeshire. Chatteris Museum, from the Neville Angell estate. CHSCM:2015.07

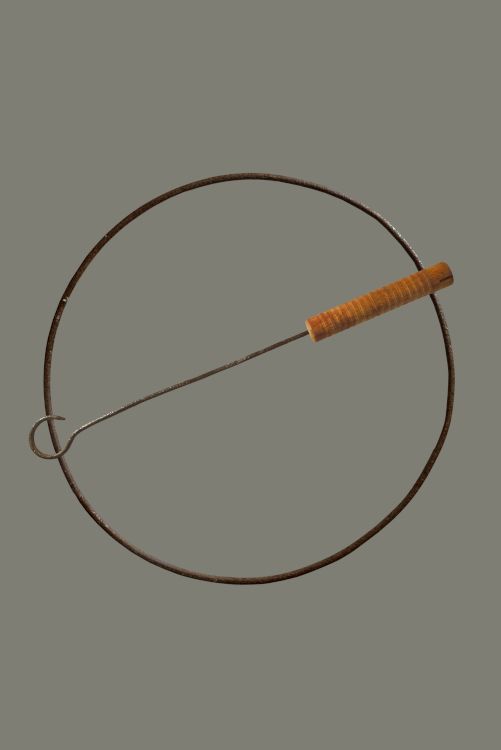

Hoop and stick. As we can see from Bruegel's Children's Games, the hoop and stick was a popular game in the sixteenth century. Its first recorded use was by the Greeks and Romans, remaining a favourite toy in the nineteenth century. 19th century. England. March and District Museum, MRHMM: 3877e

Hoop and stick. As we can see from Bruegel's Children's Games, the hoop and stick was a popular game in the sixteenth century. Its first recorded use was by the Greeks and Romans, remaining a favourite toy in the nineteenth century. 19th century. England. March and District Museum, MRHMM: 3877e

21 lead birds and beasts. Lead toys have been found from as early as the late thirteenth century, and became more widespread by the end of the medieval period. This type of toy is a predecessor to more recent tin toys. Medieval. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire. MAA 1905.3

21 lead birds and beasts. Lead toys have been found from as early as the late thirteenth century, and became more widespread by the end of the medieval period. This type of toy is a predecessor to more recent tin toys. Medieval. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire. MAA 1905.3

Model train and carriage. This wooden train consisting of an engine and one carriage is painted with the initials of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway, one of the largest suburban railway networks, which ran from 1846 to 1922. The production of toy trains began with the introduction of the railways in the 1820s and continues to this day. c.1890. England. Museum of Cambridge CAMFK:418.54

Model train and carriage. This wooden train consisting of an engine and one carriage is painted with the initials of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway, one of the largest suburban railway networks, which ran from 1846 to 1922. The production of toy trains began with the introduction of the railways in the 1820s and continues to this day. c.1890. England. Museum of Cambridge CAMFK:418.54

Children's Games (Kinderspiele)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1560

© KHM-Museumverband

A child today is just as likely to play with a stick they've picked up off the ground as a specially made toy. This painting shows this was also the case in 1560. It is an extraordinary record of the types of games and playthings children used and made, depicting over 250 children taking part in 80 different activities. Many did not use specially made toys, instead the children have made up games using objects they found.

How many of the games do you recognise?

A Child's Place

The link between children and toys is obvious. But children in the past did more than just play. They weren't just a part of society - they contributed to it.

Children helped to make jugs for the family pottery, ten-year-olds left home to work on farms, a child learned how to hunt using a miniature bow. These activities have often been overlooked by archaeologists, but they left traces behind.

At first glance many of the objects in the sections below may not obviously relate to children. Look closely. Beyond the broken piece of pottery and small gold studs you'll find evidence for the place of children in society.

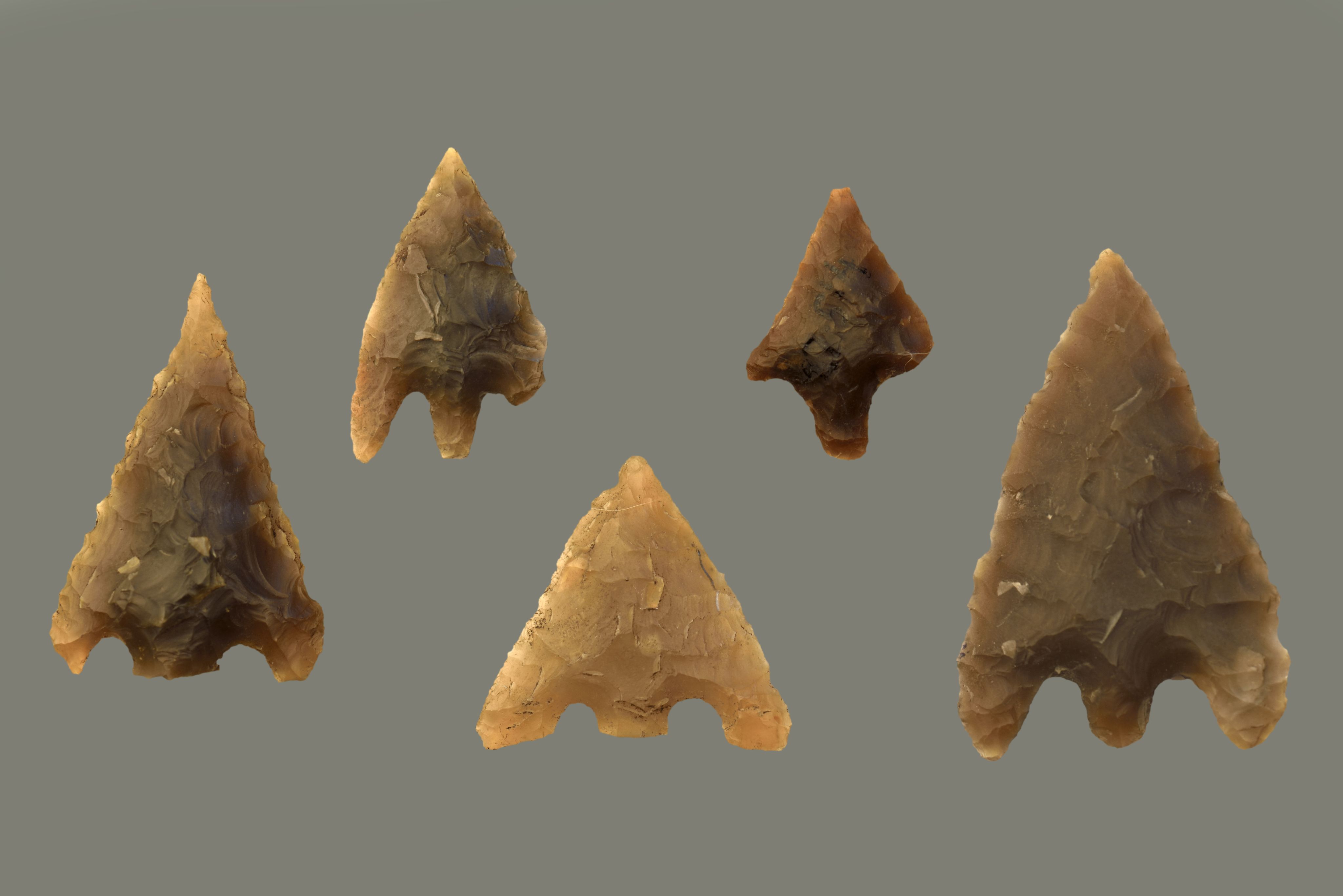

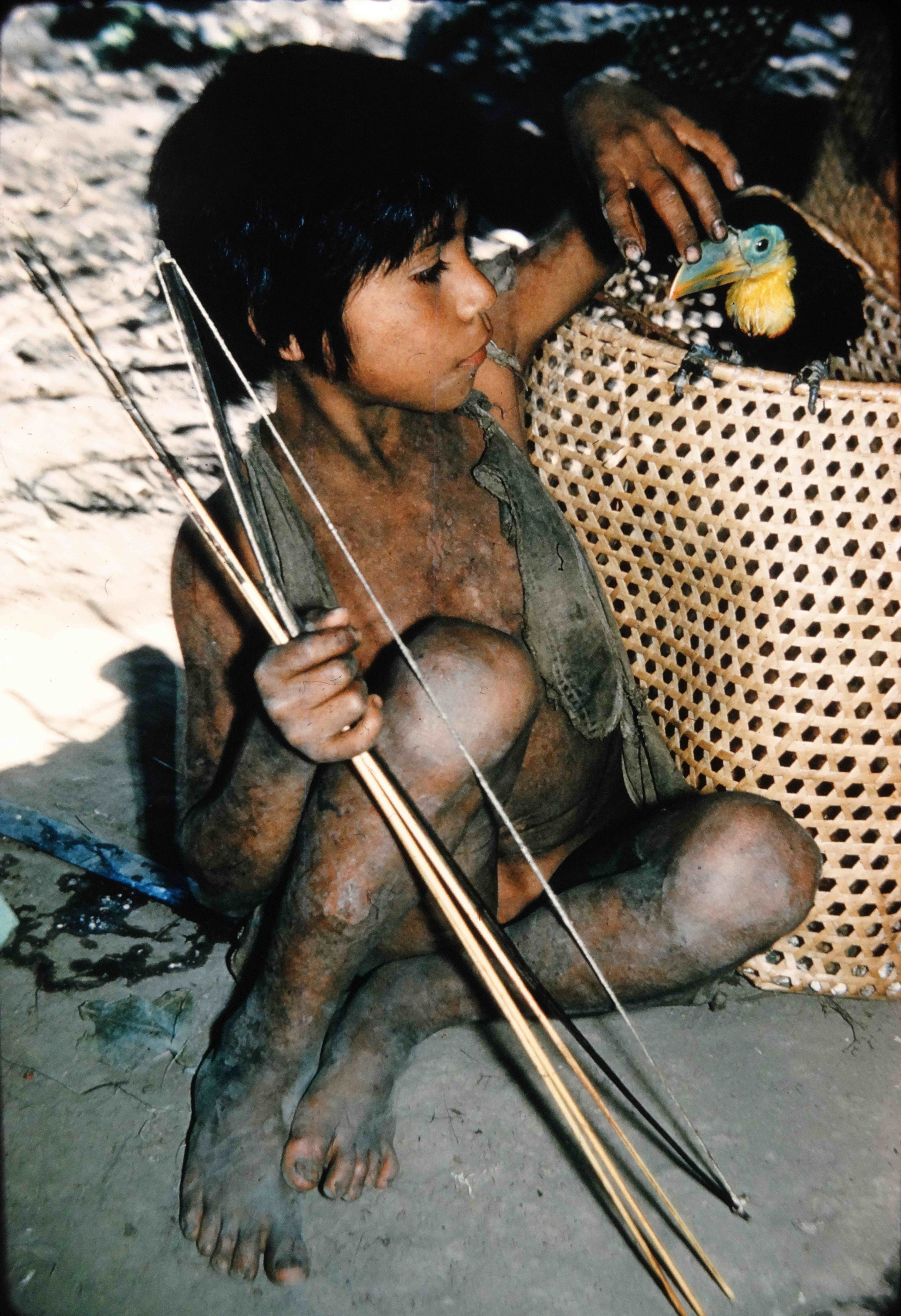

Archery: A Skill for Life

Archery was important in Bronze Age England. We can see this from surviving evidence such as stone arrowheads. Looking to the more recent past, from the Plains of America to the Mongolian Steppes, children were given small bows to master the skills of archery at a very young age. This was probably the case in the Bronze Age.

This bow (below) was originally interpreted by archaeologists as being used by an adult for a votive or religious function. Comparisons with more recent societies provide an alternative: this bow was used by a Bronze Age child.

Scroll down a little to see a painted wooden bow and three arrows collected by Mary Alicia Owen, who noted how Meskwaki children used them: "All the little boys and many of the little girls are skilled archers. They use the sharp arrows to kill rabbits and squirrels, the blunt ones to break the necks of birds and field mice."

Miniature bow shaped from red deer antler. Found in a pit at a Bronze Age settlement, archaeologists don't fully understand why it was deposited there. Bronze Age, 1700 - 1600 BCE. Isleham, Cambridgshire. MAA, 1997.11

Miniature bow shaped from red deer antler. Found in a pit at a Bronze Age settlement, archaeologists don't fully understand why it was deposited there. Bronze Age, 1700 - 1600 BCE. Isleham, Cambridgshire. MAA, 1997.11

Barbed and tanged flint arrowheads are found across western and Central Europe. They demonstrate how important bows and arrows were for hunting and warfare. Archery was a vital skill for children to learn. Early Bronze Age, 2500 - 1500 BCE. Burnt Fen, Littleport, Cambridgeshire. MAA

Barbed and tanged flint arrowheads are found across western and Central Europe. They demonstrate how important bows and arrows were for hunting and warfare. Archery was a vital skill for children to learn. Early Bronze Age, 2500 - 1500 BCE. Burnt Fen, Littleport, Cambridgeshire. MAA

Wooden child's bow. Late 19th century. Collected from the Meskwaki Nation near Tama, Iowa, USA. MAA, D.1976.239 A

Wooden child's bow. Late 19th century. Collected from the Meskwaki Nation near Tama, Iowa, USA. MAA, D.1976.239 A

Arrows with metal arrowheads and feathers. Late 19th century. Collected from the Meskwaki Nation near Tama, Iowa, USA. MAA, D 1976.239 A, D, J, and L

Arrows with metal arrowheads and feathers. Late 19th century. Collected from the Meskwaki Nation near Tama, Iowa, USA. MAA, D 1976.239 A, D, J, and L

Photograph of a young boy with a toucan holding a small bow and arrows used to hunt small birds. Photograph by Brian Moser or Donald Taylor. 1960-1961. Sierra de Perija, Colombia. MAA, T.120394

Photograph of a young boy with a toucan holding a small bow and arrows used to hunt small birds. Photograph by Brian Moser or Donald Taylor. 1960-1961. Sierra de Perija, Colombia. MAA, T.120394

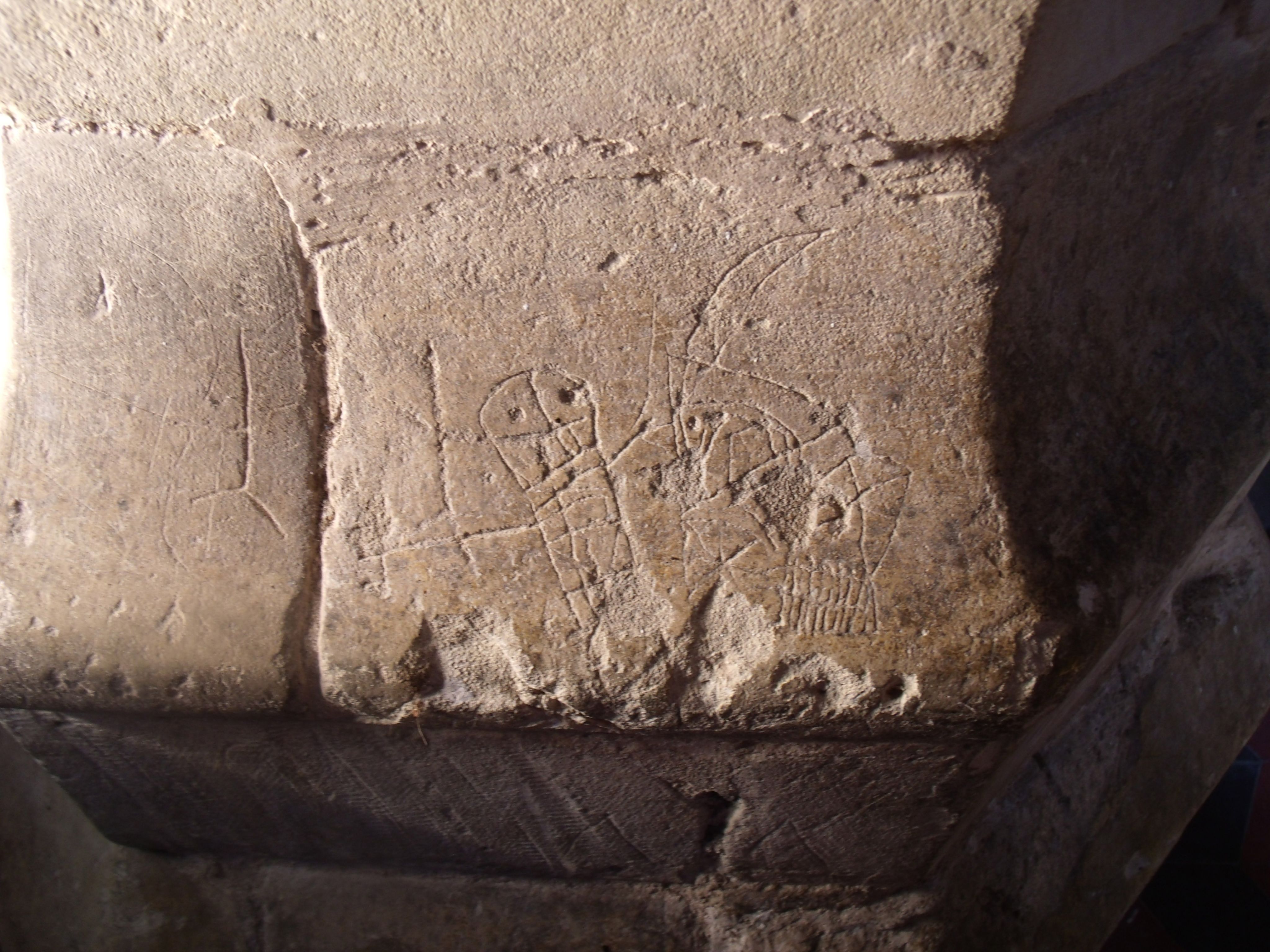

Here be dragons

The image below of a knight and a beast was carved into the base of a column in the village church at Marsham, Norfolk. We think it shows St George fighting the dragon.

The dragon has no feet. Instead the artist has drawn what looks like the fringe or skirt of a medieval costume. Religious plays were popular in the medieval period. Did a play of George and the Dragon excite the imagination of a child, inspiring them to scratch the figures into the base of a column?

Marsham, Norfolk. Medieval (1066 - 1550 CE). © Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey

Marsham, Norfolk. Medieval (1066 - 1550 CE). © Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey

Do you see the children playing on hobby horses in this medieval manuscript (dating to 1490 - 1510)?

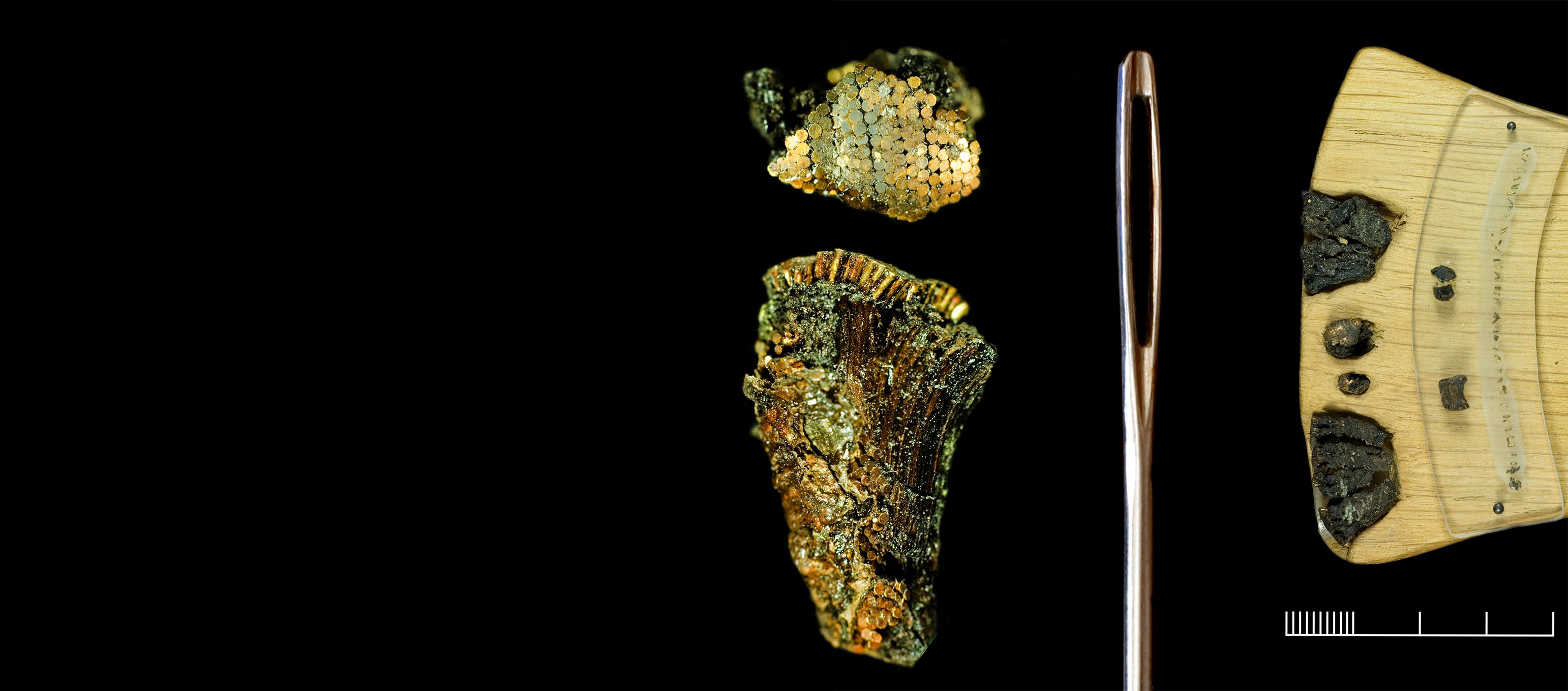

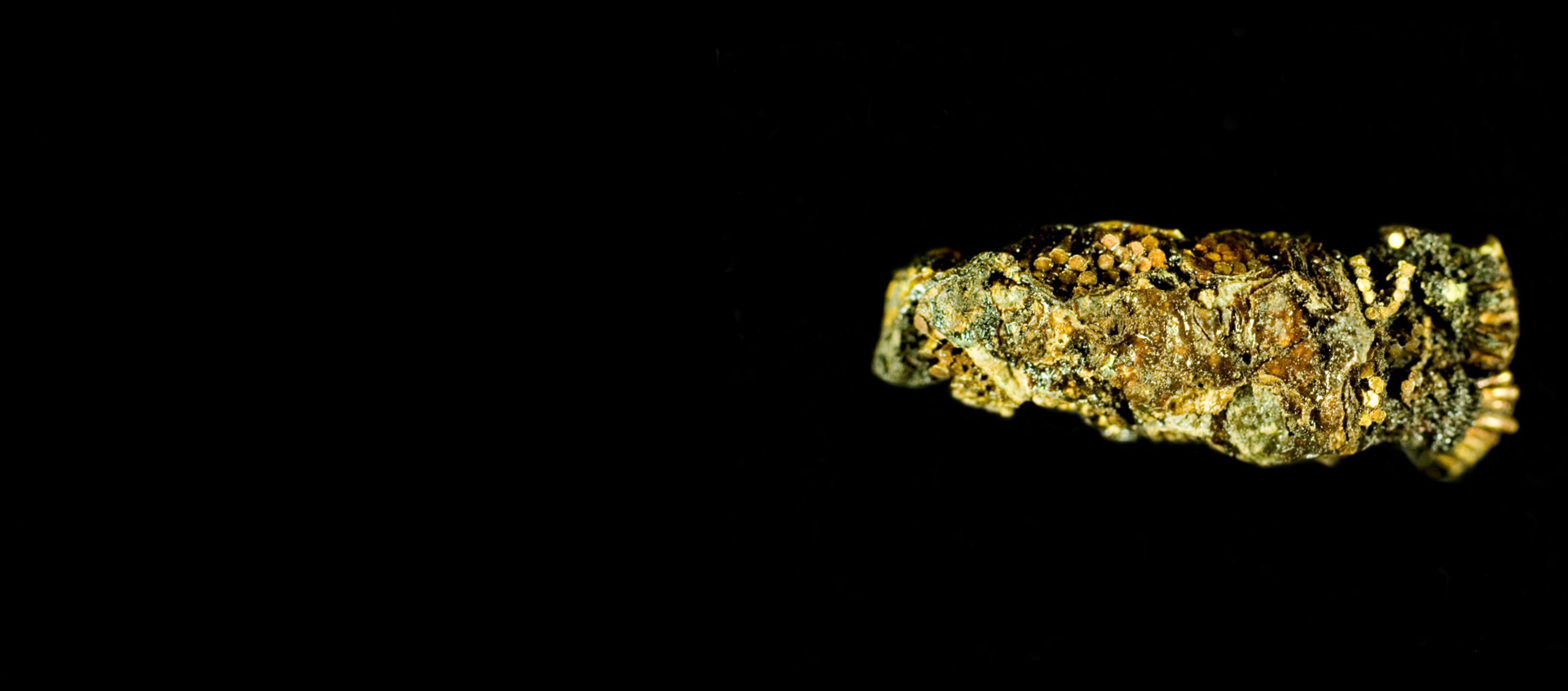

A Child's Eye View

Early Bronze Age, 1900 - 1700 BCE

Bush Barrow, Normanton Down, Wiltshire

Wiltshire Museum, Devizes, DZSWS:STHEAD.157a

At first glance, it is hard to imagine these small gold studs had anything to do with children. They were, after all, found near Stonehenge in the richly furnished grave of a Bronze Age adult.

A dagger handle from the burial was covered with thousands of these gold studs, each as fine as a human hair. In a world without magnifying glasses, excellent eyesight was needed to make and fix them to the handle. Recent research suggests that, because of their superb vision, children as young as 10 may have performed this task. This work came at a price - lasting damage to their sight.

Around 140,000 gold studs were used to decorate the dagger handle. The studs are so small, archaeologists had to use magnifying glasses to locate them in the soil.

Reconstruction of how the base of the dagger handle may have looked. Taken from an original watercolour in The History of Ancient Wiltshire (1812).

Reconstruction of how the base of the dagger handle may have looked. Taken from an original watercolour in The History of Ancient Wiltshire (1812).

Learning From Your Mistakes

Take a close look at this seemingly random assortment of pots from Eastern England. Many were once dismissed as poorly made. This may be true, but not because they were made in a hurry. They were probably made by learners.

Becoming a potter takes many years and in the past children would have started to learn as young as five. They first learned to create small, simple pots and then progressed to larger vessels and more complicated techniques.

To identify pots made by learners, you can look for tell-tale mistakes and compare them to ideal forms made by skilled potters.

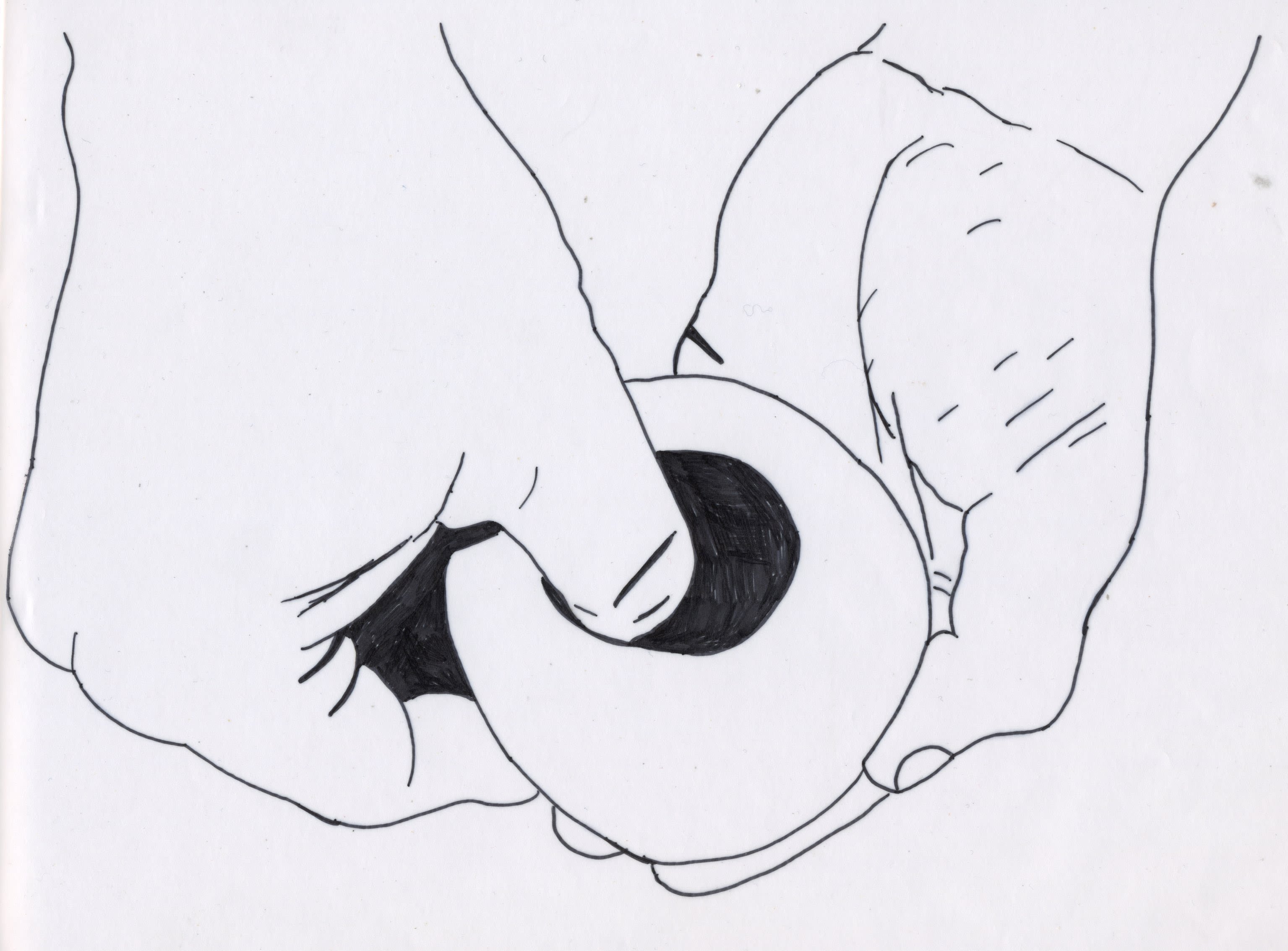

Pinch pot technique

Pinch pot technique

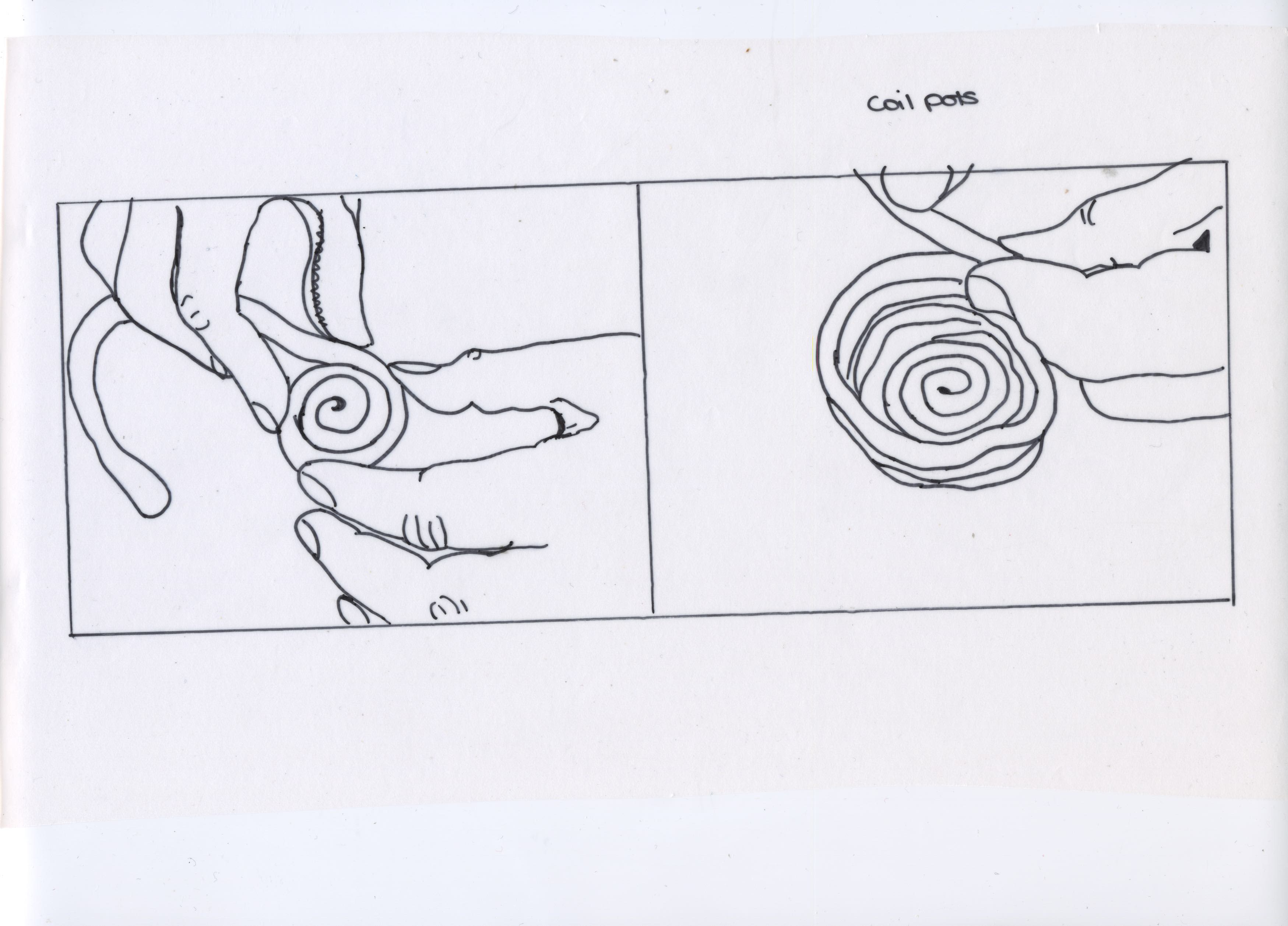

Coiling technique

Coiling technique

Bronze Age Collared Urn: These vessels - named after their heavy 'collar' - are very difficult to make well. Any small error is exaggerated as the vessel grows larger. The potter who made this urn was extremely skilled, expertly balancing the narrow base and wide mouth. Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Chippenham, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1934.1040.

Bronze Age Collared Urn: These vessels - named after their heavy 'collar' - are very difficult to make well. Any small error is exaggerated as the vessel grows larger. The potter who made this urn was extremely skilled, expertly balancing the narrow base and wide mouth. Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Chippenham, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1934.1040.

Iron Age Vessels: This vessel was made by an experienced potter. It was smooth, symmetrical walls of even thickness that have been burnished - rubbed with a stone or bone - to create a sheen. Middle Iron Age (400 - 100 BCE). Barley, Hertfordshire. MAA, 1962.109 A

Iron Age Vessels: This vessel was made by an experienced potter. It was smooth, symmetrical walls of even thickness that have been burnished - rubbed with a stone or bone - to create a sheen. Middle Iron Age (400 - 100 BCE). Barley, Hertfordshire. MAA, 1962.109 A

Anglo-Saxon Urns: This beautifully made urn held cremated remains. It is decorated with simple yet elegant incised patterns and stamps, demonstrating the skills of a very accomplished potter. Anglo-Saxon, 5th century. Lackford, Suffolk. MAA, 1950.171 A

Anglo-Saxon Urns: This beautifully made urn held cremated remains. It is decorated with simple yet elegant incised patterns and stamps, demonstrating the skills of a very accomplished potter. Anglo-Saxon, 5th century. Lackford, Suffolk. MAA, 1950.171 A

Pinch Pots: The simplest way to make a vessel is by pinching a ball of clay into a small pot. Uneven walls and rims identify beginner potters who have yet to fully master the technique. Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Great Wilbraham, Cambridgeshire. MAA Z 14995

Pinch Pots: The simplest way to make a vessel is by pinching a ball of clay into a small pot. Uneven walls and rims identify beginner potters who have yet to fully master the technique. Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Great Wilbraham, Cambridgeshire. MAA Z 14995

Pinch Pots: The simplest way to make a vessel is by pinching a ball of clay into a small pot. Uneven walls and rims identify beginner potters who have yet to fully master the technique. Probably Iron Age (800 BCE - 43 CE). Haslingfield, Cambridgeshire. MAA, D 1914.130

Pinch Pots: The simplest way to make a vessel is by pinching a ball of clay into a small pot. Uneven walls and rims identify beginner potters who have yet to fully master the technique. Probably Iron Age (800 BCE - 43 CE). Haslingfield, Cambridgeshire. MAA, D 1914.130

Pinch Pots: The simplest way to make a vessel is by pinching a ball of clay into a small pot. Uneven walls and rims identify beginner potters who have yet to fully master the technique. Anglo-Saxon, c. 500 - 550 CE. Tuddenham, Suffolk. MAA, 1894.12/Record 4

Pinch Pots: The simplest way to make a vessel is by pinching a ball of clay into a small pot. Uneven walls and rims identify beginner potters who have yet to fully master the technique. Anglo-Saxon, c. 500 - 550 CE. Tuddenham, Suffolk. MAA, 1894.12/Record 4

Poor Material Choice: Good quality clay was an important resource, so learners probably practiced with poorer quality clay. This potter attempted a complicated shape that quickly became asymmetrical, although the poor quality clay probably did not help! Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Melbourn, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1948.345

Poor Material Choice: Good quality clay was an important resource, so learners probably practiced with poorer quality clay. This potter attempted a complicated shape that quickly became asymmetrical, although the poor quality clay probably did not help! Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Melbourn, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1948.345

Coiling: Coiled pots are made from ropes of clay, which are smoothed inside and out to join the coils together. Learners’ vessels are often asymmetrical or have ridges in the wall because they didn’t smooth them properly. Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Mildenhall, Suffolk. MAA, 1950.519 A

Coiling: Coiled pots are made from ropes of clay, which are smoothed inside and out to join the coils together. Learners’ vessels are often asymmetrical or have ridges in the wall because they didn’t smooth them properly. Early Bronze Age (2350 - 1600 BCE). Mildenhall, Suffolk. MAA, 1950.519 A

Coiling: Coiled pots are made from ropes of clay, which are smoothed inside and out to join the coils together. Learners’ vessels are often asymmetrical or have ridges in the wall because they didn’t smooth them properly. Probably Bronze Age (2350 - 800 BCE). Snailwell, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1927.1226

Coiling: Coiled pots are made from ropes of clay, which are smoothed inside and out to join the coils together. Learners’ vessels are often asymmetrical or have ridges in the wall because they didn’t smooth them properly. Probably Bronze Age (2350 - 800 BCE). Snailwell, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1927.1226

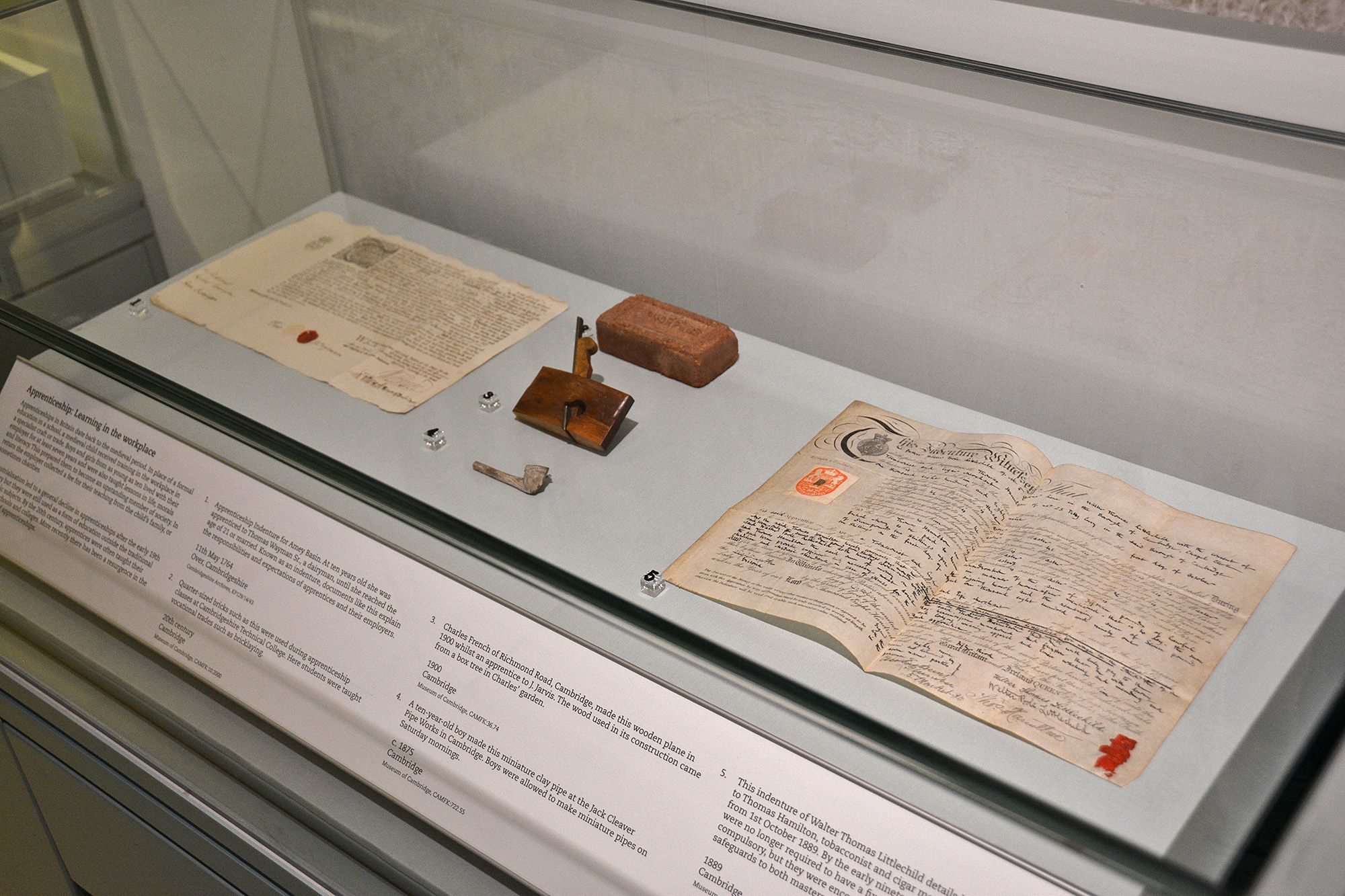

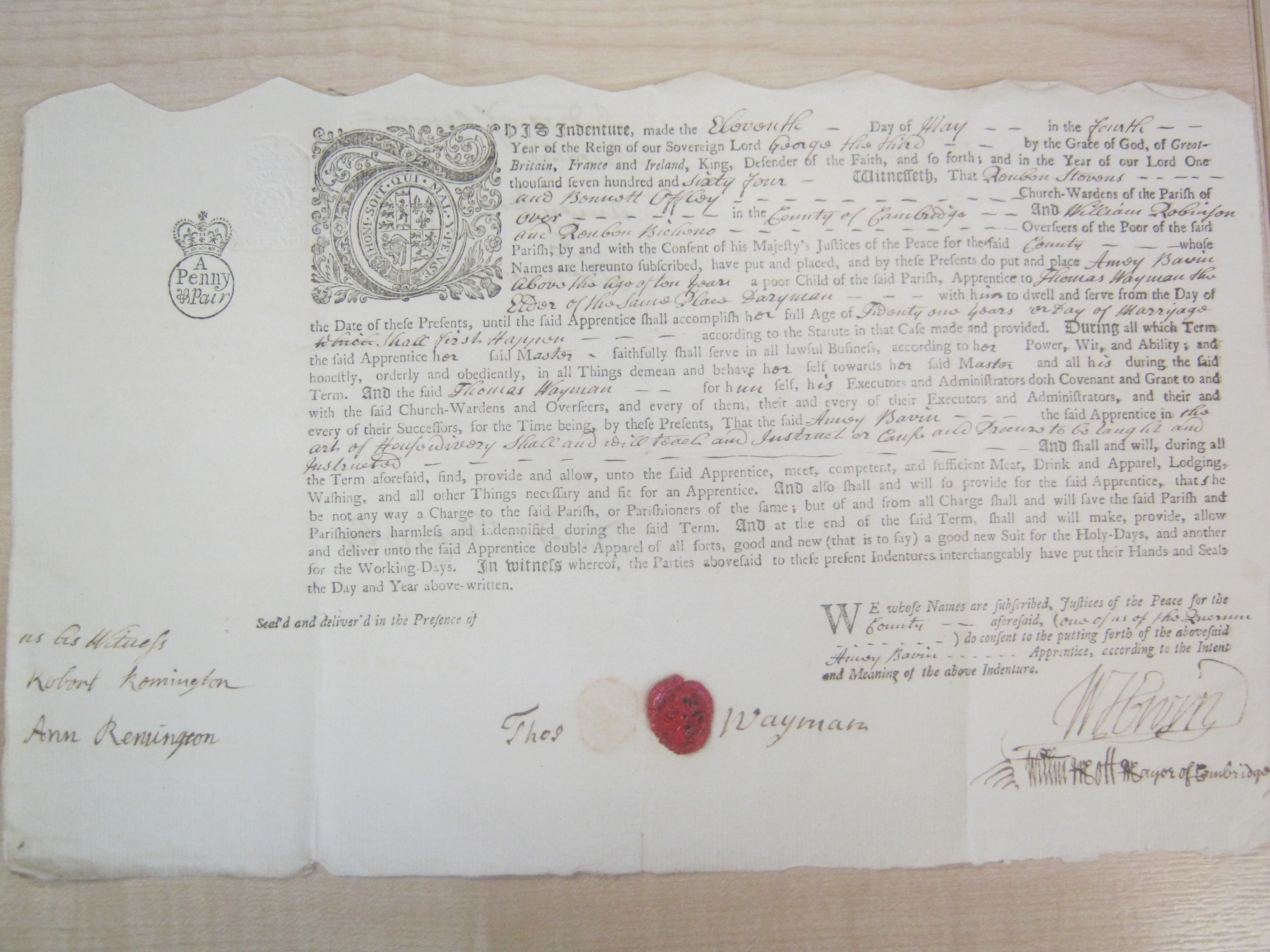

Apprenticeship: Learning in the workplace

Apprenticeships in Britain date back to the medieval period. In place of a formal education in a school, a medieval child received training in the workplace in a specialist craft or trade. Boys and girls from as young as ten lived with their employer for at least seven years and were also taught lessons in life, morals and literacy. This prepared them to become an upstanding member of society. In return the employer collected a fee for their teaching from the child’s family, or sometimes charities.

Industrialisation led to a general decline in apprenticeships after the early 19th century but they were still used as a form of education outside the traditional academic subjects. By the 20th century, apprentices were often taught their trade in schools and colleges. More recently there has been a resurgence in the popularity of apprenticeships.

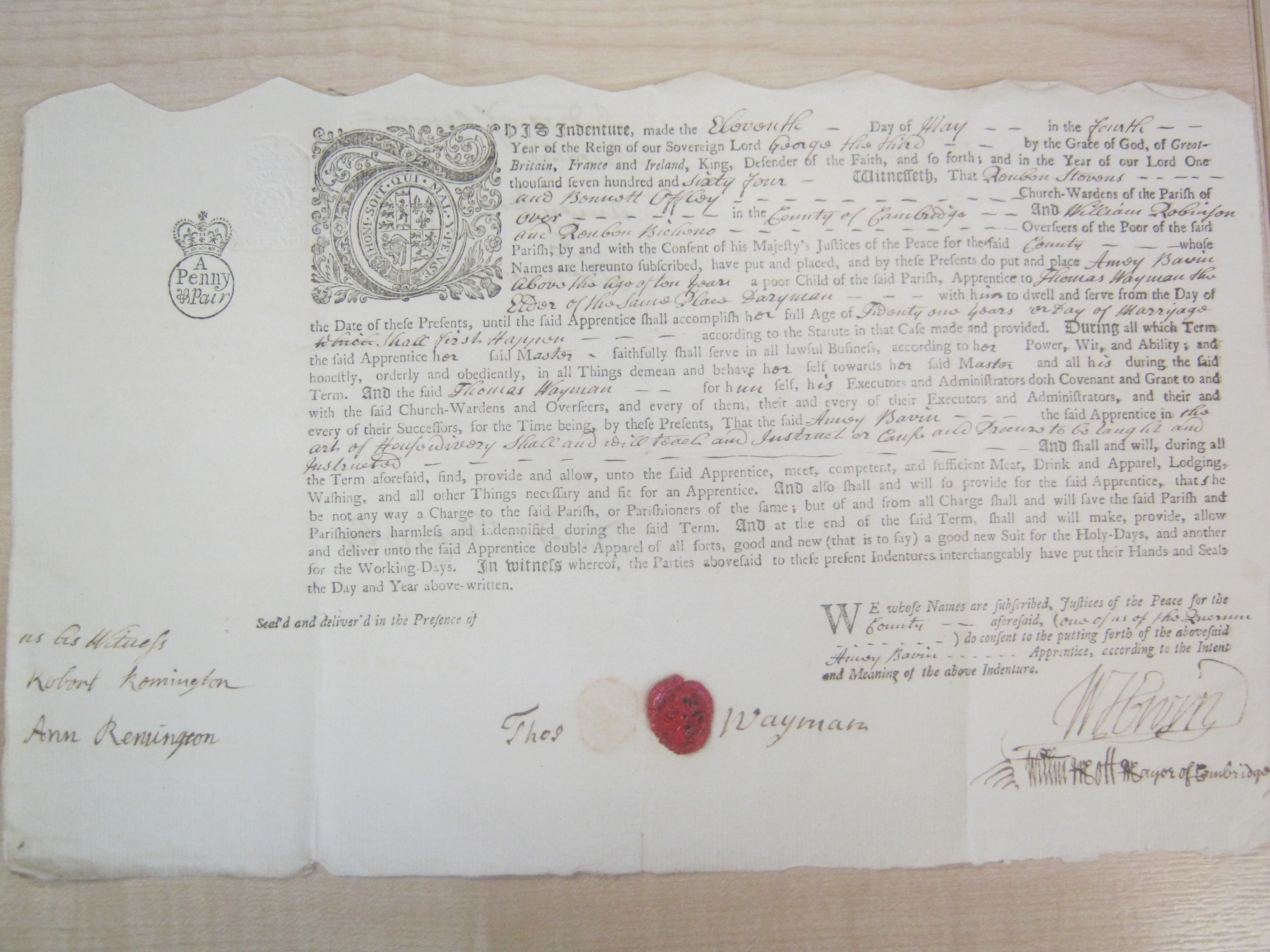

Apprenticeship Indenture for Sarah Crouch. At thirteen years old she was apprenticed to Thomas Crouch, a dairyman, until she reached the age of 21or married. It is not known whether Sarah and Thomas were related. Known as an indenture, documents like this explain the responsibilities and expectations of apprentices and their employers. 11th May 1764. Over, Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire Archives, KP129/14/43

Apprenticeship Indenture for Sarah Crouch. At thirteen years old she was apprenticed to Thomas Crouch, a dairyman, until she reached the age of 21or married. It is not known whether Sarah and Thomas were related. Known as an indenture, documents like this explain the responsibilities and expectations of apprentices and their employers. 11th May 1764. Over, Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire Archives, KP129/14/43

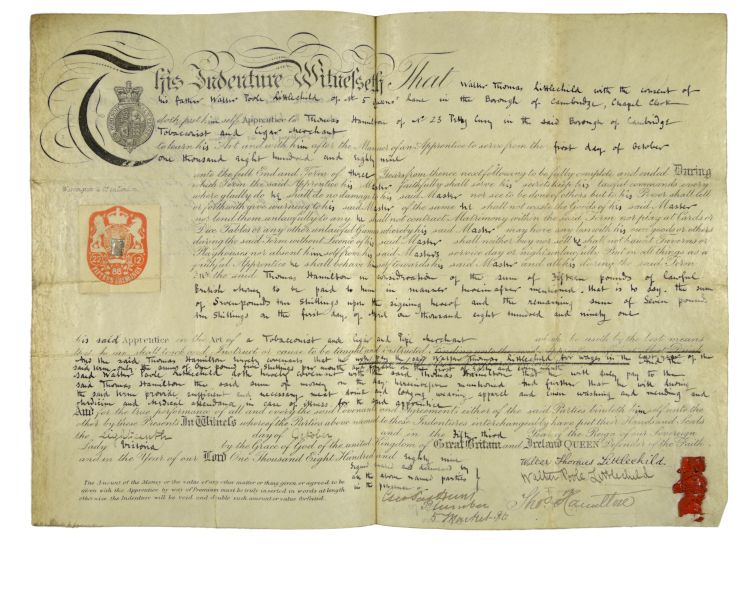

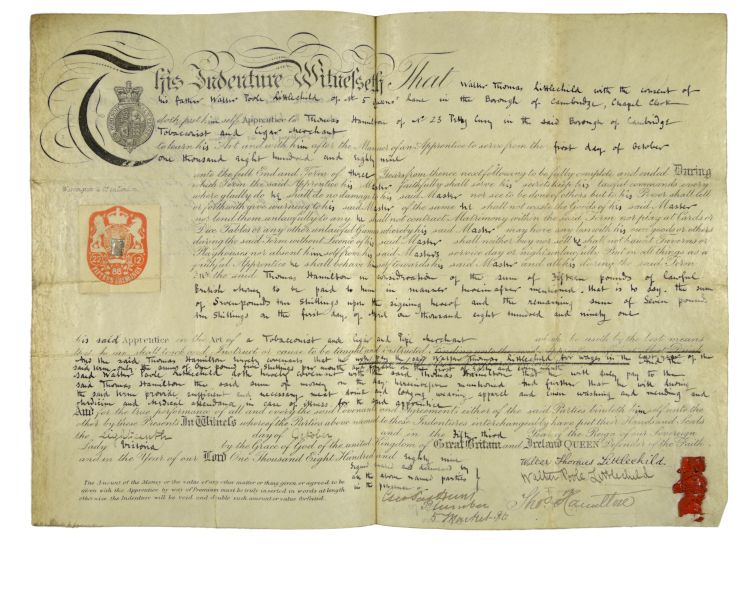

This indenture of Walter Thomas Littlechild details his apprenticeship to Thomas Hamilton, tobacconist and cigar merchant, for three years from 1st October 1889. By the early nineteenth century, apprenticeships were no longer required to have a fixed term. Indentures were not compulsory, but they were encouraged as they provided guarantees and safeguards to both masters and apprentices. 1889. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:3.71

This indenture of Walter Thomas Littlechild details his apprenticeship to Thomas Hamilton, tobacconist and cigar merchant, for three years from 1st October 1889. By the early nineteenth century, apprenticeships were no longer required to have a fixed term. Indentures were not compulsory, but they were encouraged as they provided guarantees and safeguards to both masters and apprentices. 1889. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:3.71

Break from Harvesting c.1900. March, Cambridgeshire. Probably by Henry Amos. March and District Museum, MRHMM:0N638

Break from Harvesting c.1900. March, Cambridgeshire. Probably by Henry Amos. March and District Museum, MRHMM:0N638

Quarter-sized bricks such as this were used during apprenticeship classes at Cambridgeshire Technical College. Here students were taught vocational trades such as bricklaying. 20th century. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:10.2000

Quarter-sized bricks such as this were used during apprenticeship classes at Cambridgeshire Technical College. Here students were taught vocational trades such as bricklaying. 20th century. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:10.2000

Charles French of Richmond Road, Cambridge, made this wooden plane in 1900 whilst an apprentice to J. Jarvis. The wood used in its construction came from a box tree in Charles' garden. 1900. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:36.74

Charles French of Richmond Road, Cambridge, made this wooden plane in 1900 whilst an apprentice to J. Jarvis. The wood used in its construction came from a box tree in Charles' garden. 1900. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:36.74

A ten-year-old boy made this miniature clay pipe at the Jack Cleaver Pipe Works in Cambridge. Boys were allowed to make miniature pipes on Saturday mornings. c.1875. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:722.55

A ten-year-old boy made this miniature clay pipe at the Jack Cleaver Pipe Works in Cambridge. Boys were allowed to make miniature pipes on Saturday mornings. c.1875. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:722.55

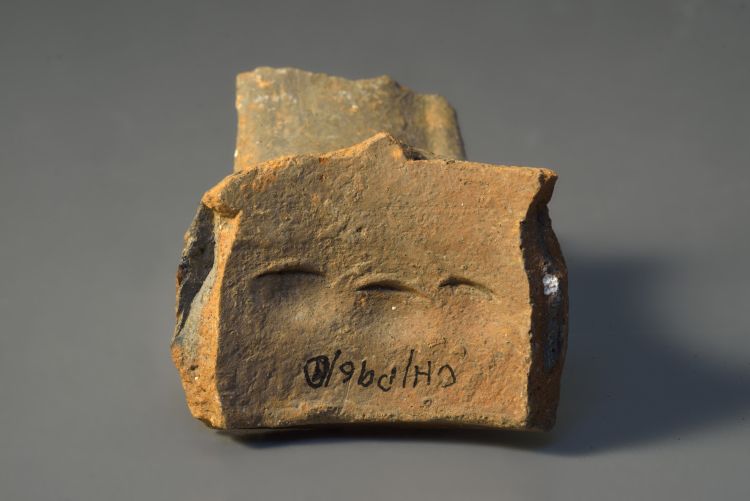

Doing Their Bit

'[What craftsman] is so negligent of his child's profit that he does not instruct him in crafts when he is young...?'

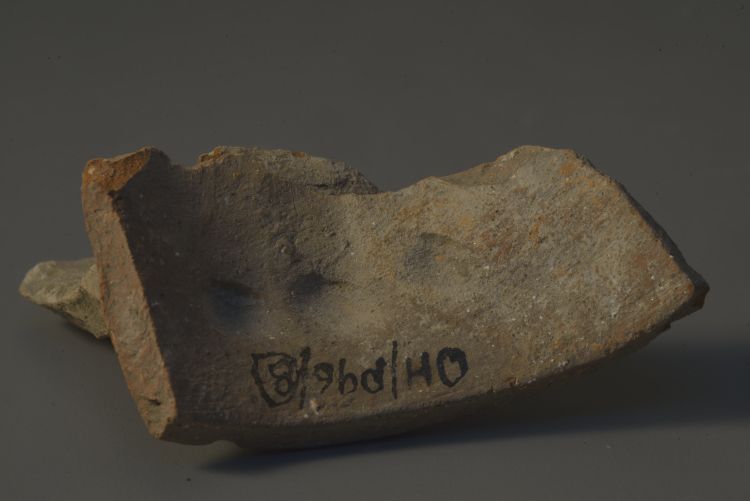

By the age of seven, children in medieval England were expected to contribute to family work, such as minding siblings or feeding chickens. For one household in Buckinghamshire, this meant helping with the family pottery business.

These pottery fragments are from the rims of jugs. Look closely to see small finger-marks where children pinched the clay to fix the handle to the rims. This was an early stage of the learning process, where the adult made the jug and the child attached the handle.

How old do you think the children were who made these finger-marks?

Rim and handle, and five sherds, from pottery jugs. 14th century. Only Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM: 1977.35.9 and 1977.35

Rim and handle, and five sherds, from pottery jugs. 14th century. Only Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM: 1977.35.9 and 1977.35

Close up of finger-marks on rim and handle from a pottery jug. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35.9

Close up of finger-marks on rim and handle from a pottery jug. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35.9

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

Five sherds from the rim of pottery jugs, with finger-marks. 14th century. Olney Hyde, Buckinghamshire. Bucks County Museum Trust, AYBCM:1977.35

16th Century Schooling

'Rule 34: Ink, parchment, knife, pens, notebooks, let all have ready.

Rule 50: Dice, knuckle-bones, quoits, and all games unworthy of a free man are to be avoided.'

For most children in fifteenth and sixteenth century England, an education involved learning through work or an apprenticeship. The growing number of free day schools meant formal schooling was a possibility for some, mainly boys from well-off families who could afford for at least one child not to work. During this period an estimated 5% of boys aged 7-18 were enrolled in schools.

Most evidence for formal education comes from written accounts, but this does not always give the whole story and sometimes archaeology can provide a glimpse into the schoolroom.

Stalls at St John's Hospital

Nathaniel Troughton

mid-19th century

History Centre, Coventry

This drawing looks to be of a church, but is actually the scene of a school. The boys attending Coventry Free Grammar School in the mid-sixteenth century sat in the choir stalls shown here for their lessons. When the school moved site, the choir stalls were moved too. This illustration is of the seats in their new location of St. John’s Hospital, Coventry where several still survive today.

This bronze plate was once set into a hornbook, a wooden paddle that held a sheet with the letters of the alphabet protected by a thin sliver of horn (see next image). The hornbook was used to teach children to read, although some were surely tempted to use it as a bat! c 1500. North Street, Exeter. Royal Albert Memorial Museum, 300/1998/M141

This bronze plate was once set into a hornbook, a wooden paddle that held a sheet with the letters of the alphabet protected by a thin sliver of horn (see next image). The hornbook was used to teach children to read, although some were surely tempted to use it as a bat! c 1500. North Street, Exeter. Royal Albert Memorial Museum, 300/1998/M141

Hornbook. Image: © Trustees of the British Museum

Hornbook. Image: © Trustees of the British Museum

Excavations of the Coventry Free Grammar School (1537-1558) uncovered everyday items that schoolboys used during their classes. Evidence for games, some forbidden, shows the school was also a time for fun and rule breaking. This inkwell is marked with the owner's initials (HW), since students had to provide their own ink. Herbert Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1994.88.2

Excavations of the Coventry Free Grammar School (1537-1558) uncovered everyday items that schoolboys used during their classes. Evidence for games, some forbidden, shows the school was also a time for fun and rule breaking. This inkwell is marked with the owner's initials (HW), since students had to provide their own ink. Herbert Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1994.88.2

Excavations of the Coventry Free Grammar School (1537-1558) uncovered everyday items that schoolboys used during their classes. Evidence for games, some forbidden, shows the school was also a time for fun and rule breaking. Students used the pointed end of the stylus to write on wax tablets and the other end as an eraser. Often the tip is missing, as in one of these examples. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1986.11.189 & .291

Excavations of the Coventry Free Grammar School (1537-1558) uncovered everyday items that schoolboys used during their classes. Evidence for games, some forbidden, shows the school was also a time for fun and rule breaking. Students used the pointed end of the stylus to write on wax tablets and the other end as an eraser. Often the tip is missing, as in one of these examples. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1986.11.189 & .291

Schoolboys used iron knives to make pens from goose quills and to cut their meat at mealtime. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1986.11.1.3

Schoolboys used iron knives to make pens from goose quills and to cut their meat at mealtime. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1986.11.1.3

Book clasps held books shut to protect them from moisture when they were not in use. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR.1986.11.146

Book clasps held books shut to protect them from moisture when they were not in use. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR.1986.11.146

These counters were used in games of draughts or perhaps as chips to tally gaming gains and losses. Games resembling gambling were forbidden, rules some students apparently ignored. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1986.11.113, .208, & .213

These counters were used in games of draughts or perhaps as chips to tally gaming gains and losses. Games resembling gambling were forbidden, rules some students apparently ignored. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR. 1986.11.113, .208, & .213

These marbles are amongst the oldest ever found in England. Up to six boys could compete against each other using the gaming board found carved into one of the school's desktops... if the teacher wasn't looking. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR.1986.11.207

These marbles are amongst the oldest ever found in England. Up to six boys could compete against each other using the gaming board found carved into one of the school's desktops... if the teacher wasn't looking. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, AR.1986.11.207

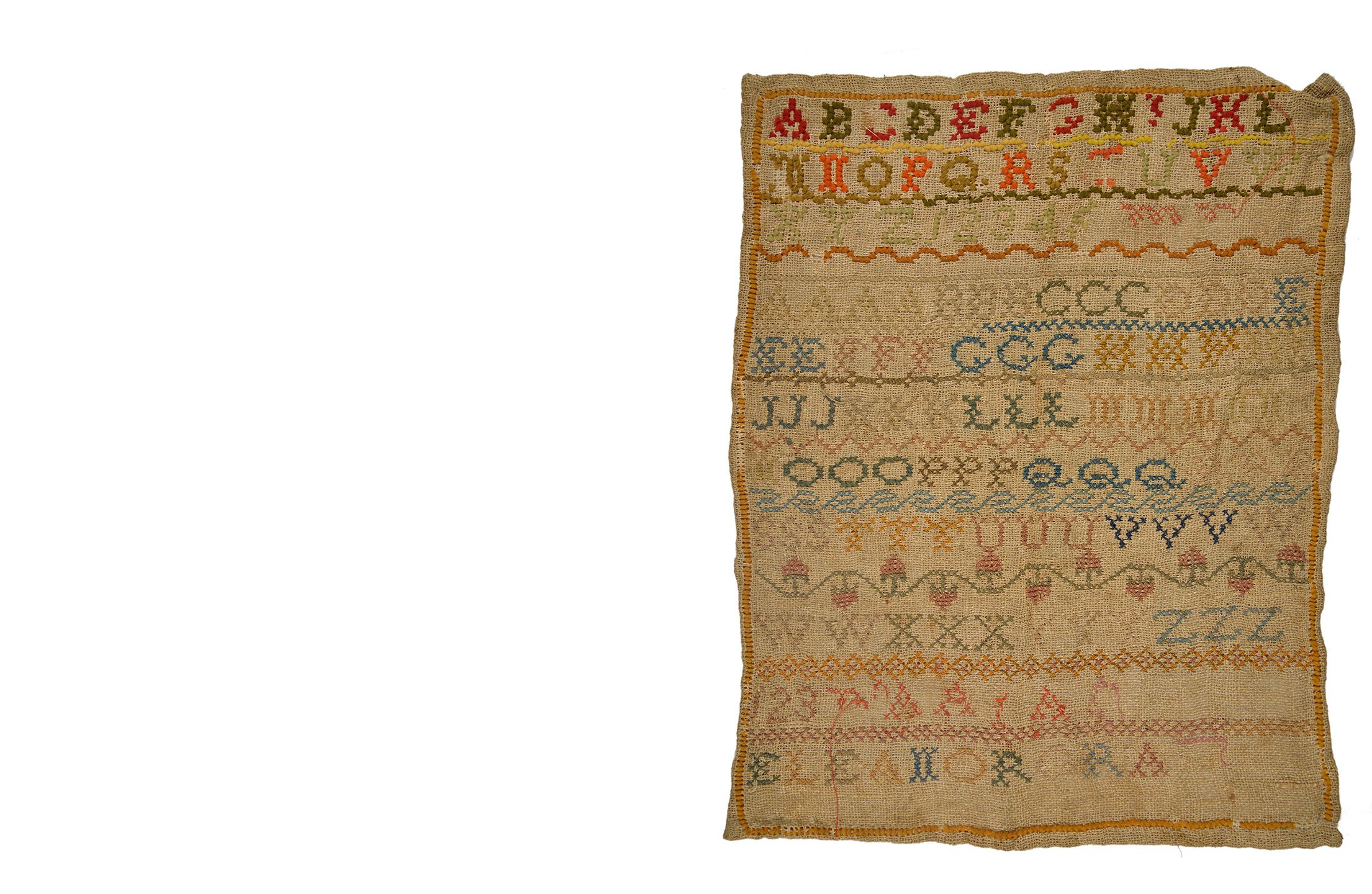

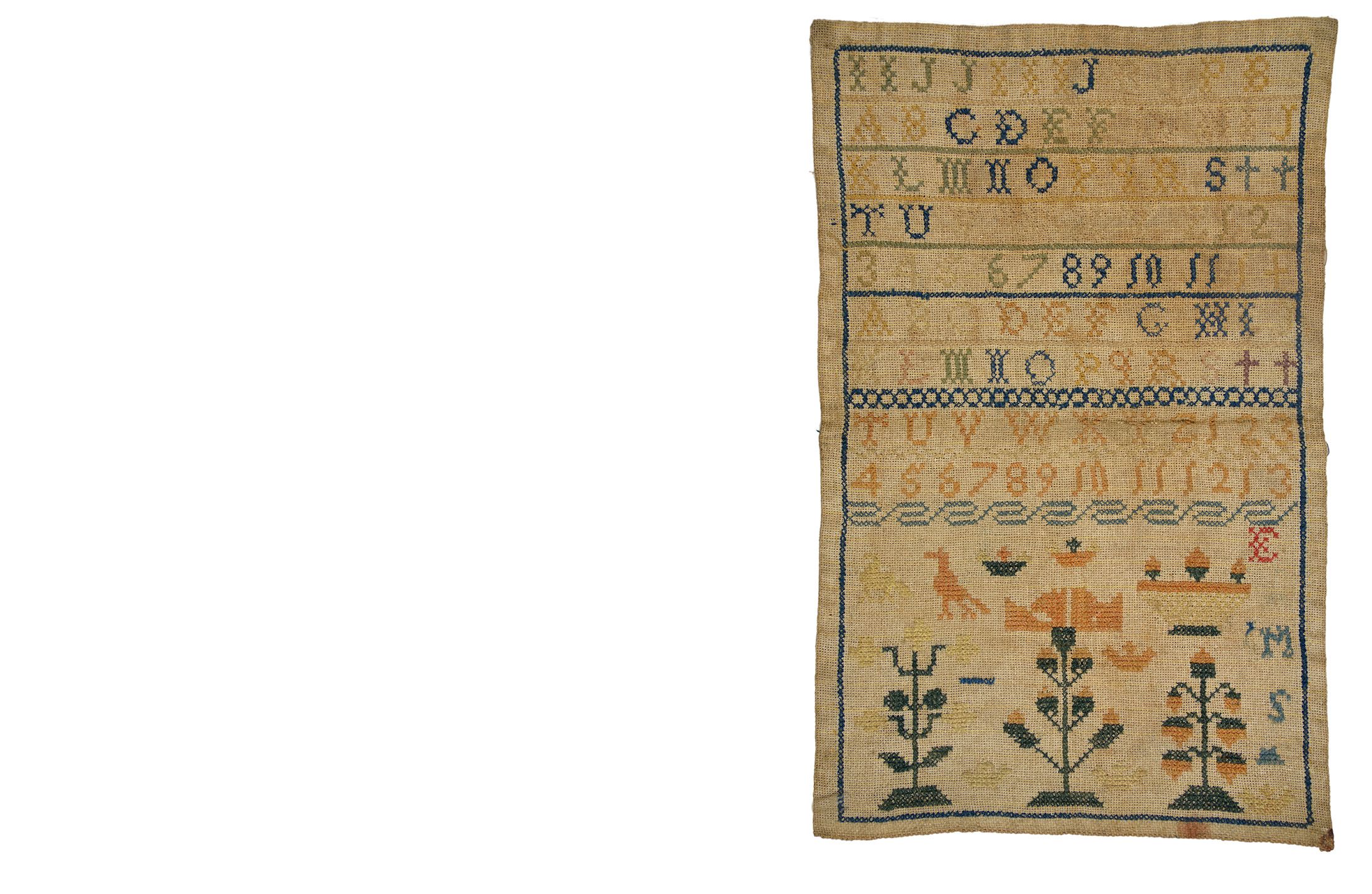

A Stitch in Time

Samplers were first made in the sixteenth century and are still being made today. During their long history their form and function changed. What was once created as a practical tool - a reference for stitches and patterns used by embroiderers - played an integral role in the education of young girls.

Three generations of girls from the same family, all named Eleanor, stitched these samplers during the first half of the nineteenth century. They demonstrate skills important for young girls to master, including literacy, numeracy and needlework.

Eleanor Coulsen made the earliest sampler in this group when she was 13 years old. It includes a biblical scene of Adam and Eve standing either side of the tree of knowledge. To create the design Eleanor used cross-stitch and naturally dyed thread in blue and fawn to spell out her name and age in the centre and the alphabet at the top.

Eleanor Grey used many more colours in this second sampler compared to that of her mother's. Cross-stitch was used to demonstrate her skills in needlework by including the single row of strawberries and her name at the bottom, some of which is now missing.

This third sampler was made by Eleanor M.S. when she was around 10 years old. She used thread coloured with artificial dyes, a new product not available to her mother and grandmother. She used birds and trees to decorate the bottom of her sampler, common motifs used at this time.

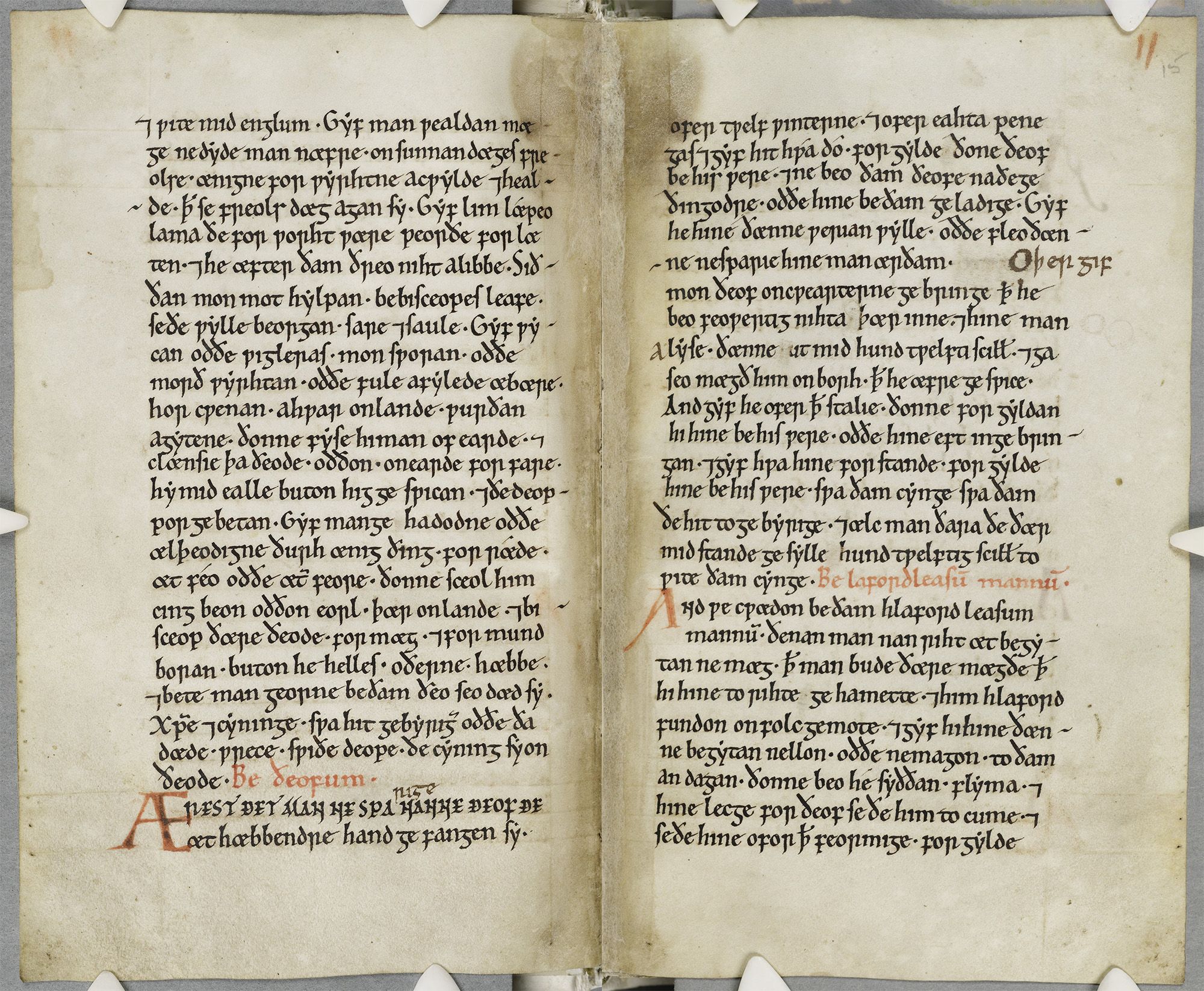

Crime and Punishment

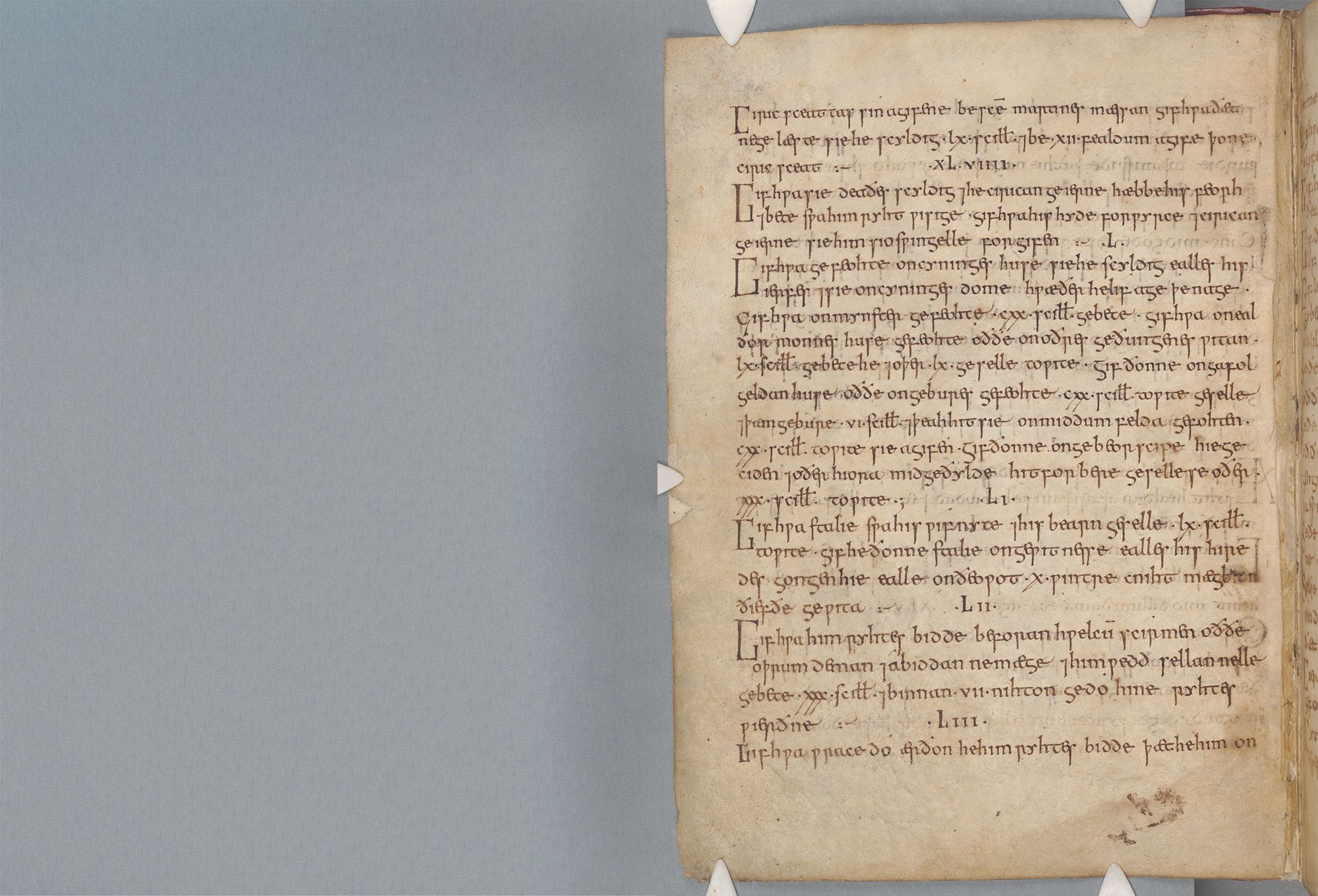

In modern England, the law typically considers anyone aged under 18 a child. In the Anglo-Saxon period, the king of Wessex, Ine (abdicated 726 CE), believed a ten year old should be punished as an adult. Two centuries later, King Aethelstan (died 939 CE) raised the age of criminal responsibility to twelve. At least in the eyes of the law, these two kings saw the transition from childhood to adulthood as somewhere between ten and twelve years old - far younger than today.

'First, no their shall be spared who is caught in the act, if he is over twelve years old and if the value is more than 8 pence.'

Although some crimes committed by children were still punishable by death, by the early nineteenth century courts were increasingly passing alternative sentences. Children as young as nine and ten were sentenced to transportation to work in the British colonies such as Australia. It wasn't until the close of the nineteenth century that children were no longer placed in adult prisons.

A facsimile of the Laws of Aethelstan, the first Anglo-Saxon king of all Britain, in which children are often referred to in relation to property law and theft. Modern copy (Original: Anglo-Saxon, 10th Century). England. Original located at the Parker Library. With thanks to the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

A facsimile of the Laws of Aethelstan, the first Anglo-Saxon king of all Britain, in which children are often referred to in relation to property law and theft. Modern copy (Original: Anglo-Saxon, 10th Century). England. Original located at the Parker Library. With thanks to the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

A pair of child's handcuffs. Late 19th century. Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire Police Museum

A pair of child's handcuffs. Late 19th century. Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire Police Museum

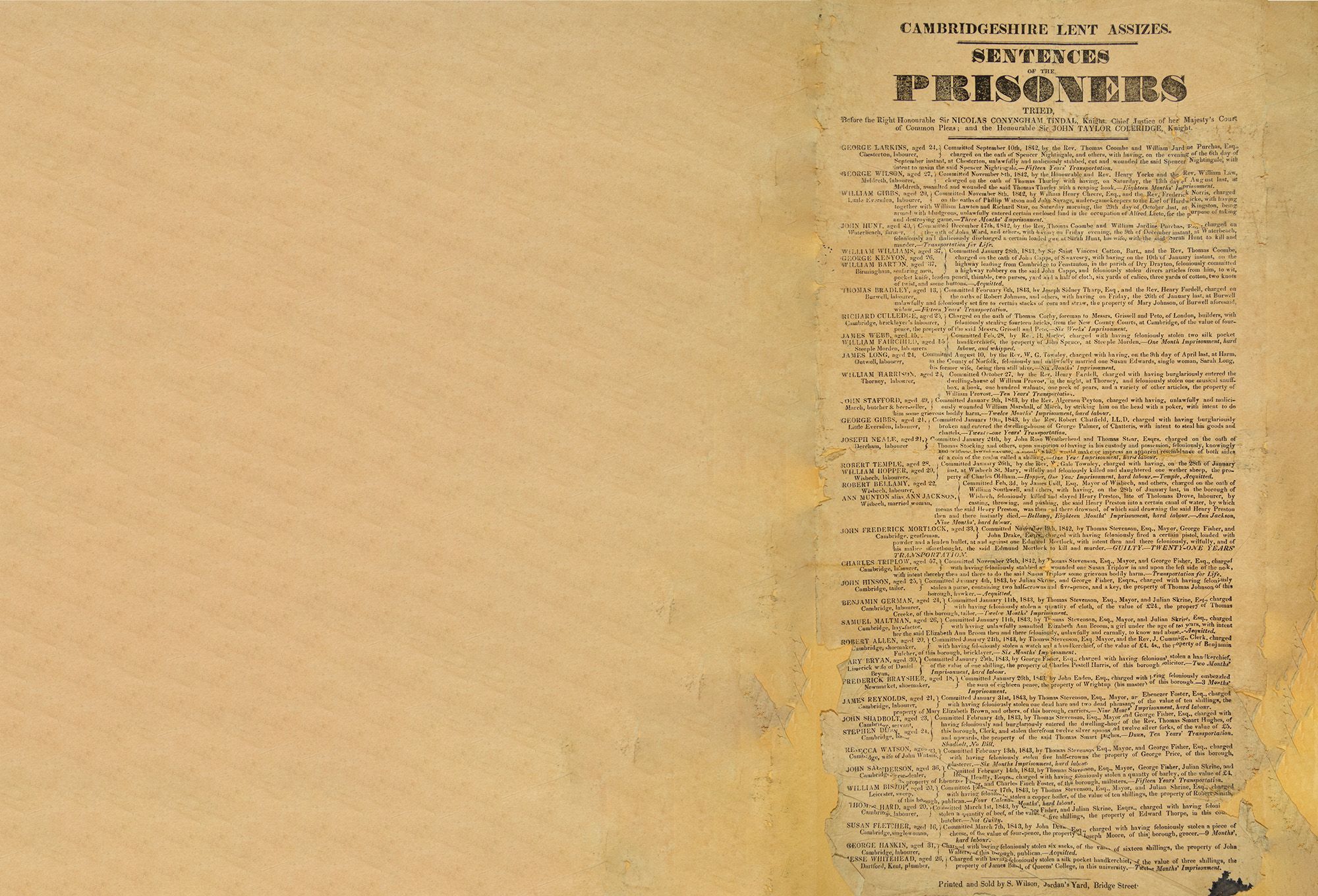

Cambridge Lent Assizes

1843, Cambridge

Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:146.61

Courts known as assizes met every 3 months to preside over the most serious local criminal cases. The Cambridge Lent Assizes of 1843 include the sorry tale of 13-year-old Thomas Bradley from Burwell, Cambridgeshire who was sentenced to 15 years transportation to Port Phillip, Australia for setting fire to stacks of corn and straw.

Laws of Ine

Anglo-Saxon, 8th century, England

Original located at the Parker Library. With thanks to the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

This image is from one of the oldest surviving manuscripts in England. It is called the Laws of Ine, after the king of Wessex who ruled until AD 726. Here Ine states that 'A ten-year-old may be regarded as an accessory to theft', and can therefore be punished as an adult - an action that could result in death.

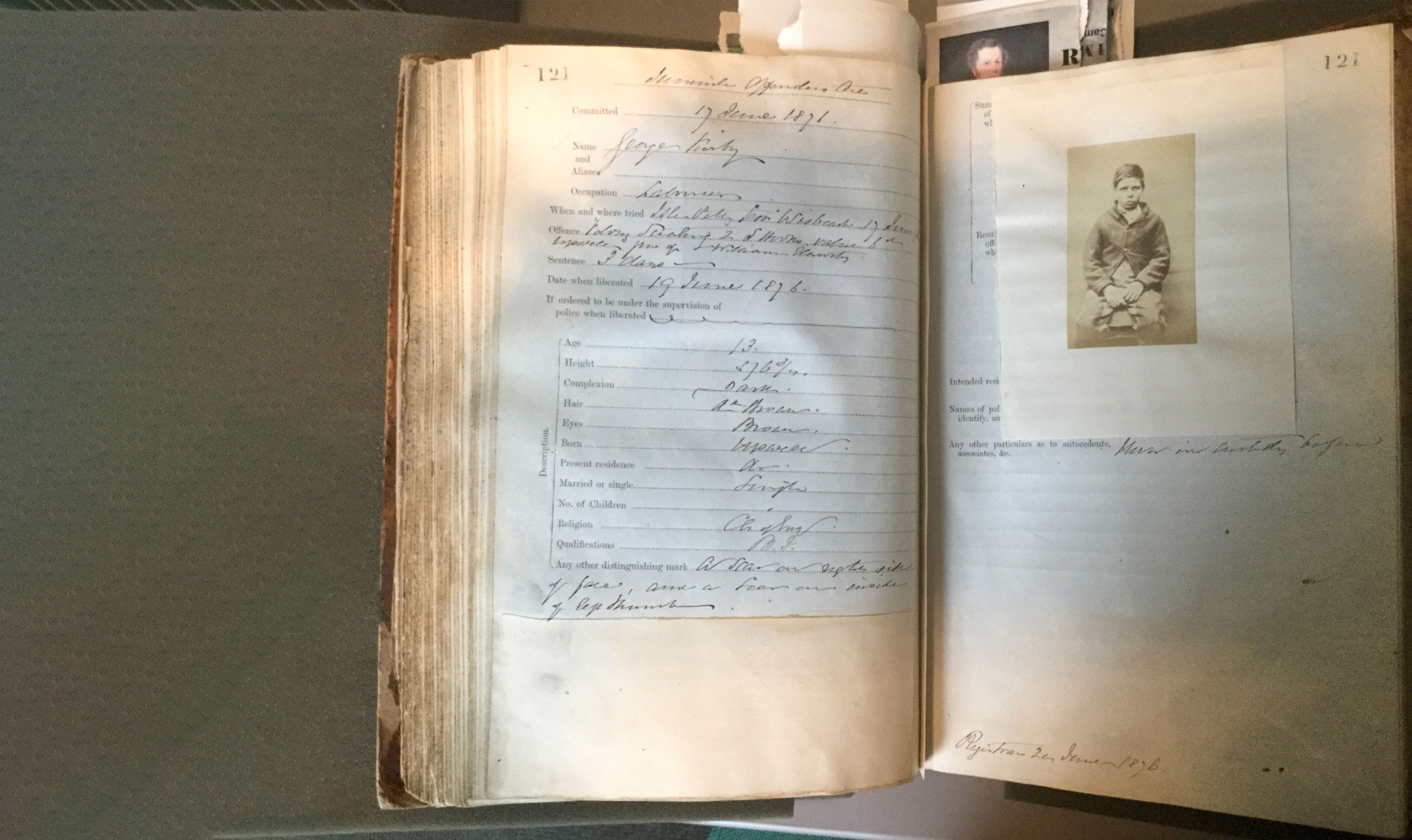

Prison register for George Kirby

17th June 1876, Wisbech, Cambridgeshire

Wisbech and Fenland Museum, WISFM:E 15/52/1-2

George Kirby from Upwell, Cambridgeshire was caught stealing 2 hooks worth 6 pence from Mr William Elansty in June 1876. For his crime he was sentenced to 3 days in prison. We can learn a lot about George from his entry in the Wisbech prisoner's register such as what he looked like and where he was from. At only 13 years old he had an occupation as a labourer, and he had never been in custody before.

Health and Wellbeing

It was dangerous being a child in the past. From prehistory until the Victorian period, 30 - 50% of children did not survive to adulthood. Disease, germs, and household accidents all took their toll. Parents tried to protect their children by following the medical advice and social customs of the time, but sometimes this advice was more dangerous than doing nothing at all.

The story of some families' attempts to prevent accidents and ensure good health for their children is preserved in some of the objects presented here.

Freeborn Roman boys were given a pendant called a bulla soon after birth, which contained an amulet to protect them against evil spirits. They wore the bulla throughout the vulnerable years of childhood until about the age of 17. This statuette is probably of the Emperor Nero as a child, wearing his protective bulla.

Roman, probably 1st century CE

Europe

MAA, 1923.238

In the Roman world, snakes were connected with healing. Perhaps the child who wore this silver snake bracelet was sick, or her parents were trying to ensure her health.

Roman (43 - 410 CE)

Ashton, Northamptonshire

Peterborough Museum and Art Gallery, PETMG:ASH1

c. 1790, Cambridgeshire. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:58b.53

c. 1790, Cambridgeshire. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:58b.53

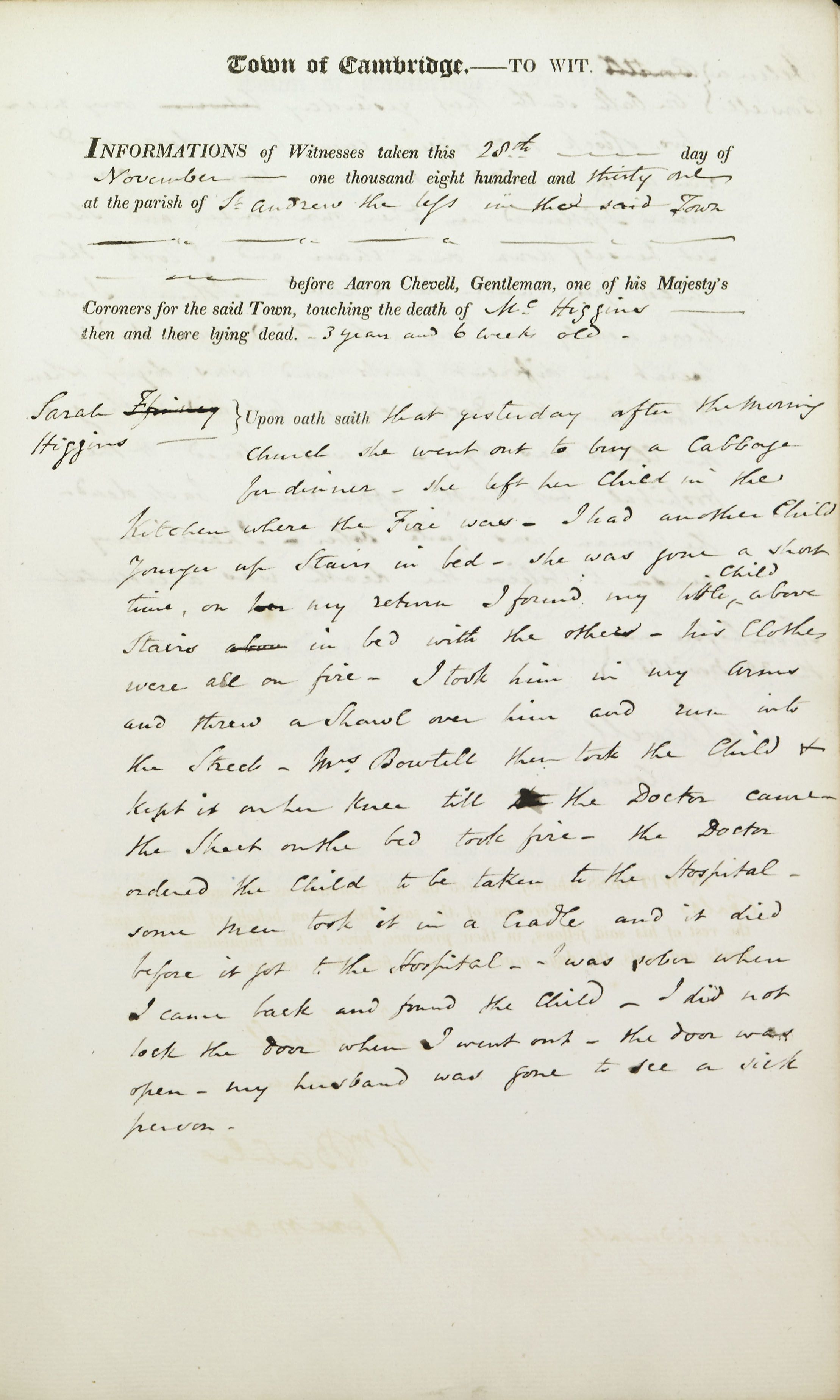

Baby Walkers

Baby walkers like this one were used from as early as the fifteenth century until the nineteenth century. They served a dual purpose: to help a child learn to walk and to protect it from falling into open fires at the home - a real danger, as the coroner's report demonstrates.

Norwich Castle Museum, MWHCM:1949.138.1

Norwich Castle Museum, MWHCM:1949.138.1

Boy with Coral, unknown artist, c. 1670

Cambridgeshire Archives, KCB/Co/2/1/66

Cambridgeshire Archives, KCB/Co/2/1/66

Coroner's report regarding the death of Michael Higgins, aged three years, who accidentally fell into the kitchen fire in 1837.

'During weaning, give the child 'water or a little watery wine through artificial teats...''

The pottery vessels below have puzzled researchers for decades. For a long time, it was thought that they were used for cooking or to fill oil lamps. The discovery of milk traces inside some bottles means that it is now thought that at least some of them were used during weaning or to replace breast-feeding. An artificial teat was probably added to the spout, which would be difficult to keep germ-free.

Pottery feeding bottle. Roman (43 - 410 CE). Harlton, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1889.13

Pottery feeding bottle. Roman (43 - 410 CE). Harlton, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1889.13

Pottery feeding bottle. Roman (43 - 410 CE). Great Chesterford, Essex. MAA, 1948.693 B

Pottery feeding bottle. Roman (43 - 410 CE). Great Chesterford, Essex. MAA, 1948.693 B

Pottery feeding bottle. Roman (43 - 410 CE). London. MAA, 1923.419 A

Pottery feeding bottle. Roman (43 - 410 CE). London. MAA, 1923.419 A

'The [artificial] nipple need never be removed till replaced with a new one... and will last for several weeks.'

Victorian inventors produced a wide variety of glass and ceramic feeding bottles fitted with rubber teats. Like the Roman versions they were difficult to keep clean and often did more harm than good.

Glass feeding bottle, c. 1870 - 1890. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:934.37

Glass feeding bottle, c. 1870 - 1890. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:934.37

Glass feeding bottle, 19th century. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:TEMP04.15

Glass feeding bottle, 19th century. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:TEMP04.15

Ceramic feeding bottle, c. 1830 - 1860. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:TEMP05.15

Ceramic feeding bottle, c. 1830 - 1860. Cambridge. Museum of Cambridge, CAMFK:TEMP05.15

Roman Tombstone

Roman (43 - 410 CE)

Risingham, Northumberland

MAA, D.1970.11

The figure in the centre of this Roman tombstone is a stylised portrait of young girl holding an apple. It seems obvious that this object should tell us a great deal about the child commemorated. In fact, the inscription only gives us when she died. It is her father's name, not hers, which is recorded.

The most that we can conclude from this tombstone is that this girl was probably a valued member of her family. The evidence that might have provided more information about her life - skeletal material, grave goods, context - is lost. It is a haunting reminder of the children who never reach adulthood.

'Quem di diligunt adolescens moritur...'

(The god's favourites die while still children...)

D M

BLESCIUS

DIOVICUS

FILIAE

SUAE

VIXSIT

AN UM

I ET DIE

XXI

To the spirits of the departed,

Blescius Diovicus

set this up to

his own daughter,

she lived

1 year and

21 days

Translation after Collingwood and Wright, 1965

Burial of a Roman Child

The grave of a one-year-old Roman child was found in Cambridgeshire in 1990. The skeleton had been carefully placed in a lead coffin. A wooden box full of ceramic figurines was placed on top of the coffin before burial.

The skeleton can tell us how old the infant was, but not whether it was a boy or a girl. Specialists can see that the child suffered from either anaemia or a parasite, but don't know if this caused the death. We know that the figurines were imported from Europe, but we are unsure whether they were intended as toys or as religious items.

The evidence raises more questions than answers about the life of this child. Future innovations may one day allow us to understand more.

Roman, 2nd century CE. Arrington, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1992.283

Roman, 2nd century CE. Arrington, Cambridgeshire. MAA, 1992.283

The lead lining seen here would have been placed inside an oak coffin. This coffin is much too large for the 1-year-old infant buried inside, implying it was not made-to-measure.

This object came from the grave of a one-year old Roman child found in Cambridgeshire in 1990. c. 130 - 160 CE

This object came from the grave of a one-year old Roman child found in Cambridgeshire in 1990. c. 130 - 160 CE

Bullock figurine. Bullock or ox figurines like this were made in central France and were considered symbols of strength by the Romans. MAA 1994.14

Bullock figurine. Bullock or ox figurines like this were made in central France and were considered symbols of strength by the Romans. MAA 1994.14

Figure of a man. This man wears a belted tunic and Persian-style cap. MAA 1994.15

Figure of a man. This man wears a belted tunic and Persian-style cap. MAA 1994.15

This female figure, seated in a chair, is known as a mother goddess and is symbolic of death and regeneration. This example was probably made in the Rhineland, Germany. MAA 1994.17

This female figure, seated in a chair, is known as a mother goddess and is symbolic of death and regeneration. This example was probably made in the Rhineland, Germany. MAA 1994.17

Ram figurine. Two almost complete figurines, and one fragment, of standing rams have been beautifully made with fine details. MAA 1994.16 A

Ram figurine. Two almost complete figurines, and one fragment, of standing rams have been beautifully made with fine details. MAA 1994.16 A

Ram figurine. Two almost complete figurines, and one fragment, of standing rams have been beautifully made with fine details. MAA 1994.16 B

Ram figurine. Two almost complete figurines, and one fragment, of standing rams have been beautifully made with fine details. MAA 1994.16 B

Figures of infants such as this are found in graves and shrines, most commonly in France. MAA 1994.11

Figures of infants such as this are found in graves and shrines, most commonly in France. MAA 1994.11

This figure is a bust of a long-hair child. MAA 1994.12

This figure is a bust of a long-hair child. MAA 1994.12

Statuette of a thorn-puller. This statuette, known as a spinario (thorn-puller), depicts a young boy pulling a thorn from his foot.MAA 1994.13

Statuette of a thorn-puller. This statuette, known as a spinario (thorn-puller), depicts a young boy pulling a thorn from his foot.MAA 1994.13

Oakington: An Exceptional Site

It is rare to find child burials from the Anglo-Saxon period. This is strange because children outnumbered adults and there was a high infant mortality rate. Archaeologists think that children may have been buried in a different way to adults, and the fragile bones of infants often do not survive long in the soil.

In 2010, archaeologists began excavating a fifth to sixth century Anglo-Saxon cemetery in Oakington, just north of Cambridge. Excavators were surprised to find that this site contained an exceptionally high proportion of child burials. Nearly half of all the burials discovered belong to individuals under the age of twelve.

Although the excavators were not looking for children, this discovery has provided a remarkable opportunity to use modern research techniques to ask new questions about children's lives in Anglo-Saxon Cambridgeshire.

Archaeologists from the University of Central Lancashire, the Manchester Metropolitan University and Oxford Archaeology East excavate at the site of Oakington. 2013, Oakington, Cambridgeshire. Photographer: Dr Duncan Sayer, University of Central Lancashire

Archaeologists from the University of Central Lancashire, the Manchester Metropolitan University and Oxford Archaeology East excavate at the site of Oakington. 2013, Oakington, Cambridgeshire. Photographer: Dr Duncan Sayer, University of Central Lancashire

Children's Pots

In the Oakington burial ground, 27% of the 128 excavated burials were of children under the age of six. Many of the burials contained small vessels. Researchers are now analysing these in the hope of identifying their contents. This may help us understand more about the young children who were buried with them.

This small vessel was found in a child's grave alongside a single animal bone. Anglo-Saxon, 5th - 6th century. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. University of Central Lancashire, Grave 54, 1346

This small vessel was found in a child's grave alongside a single animal bone. Anglo-Saxon, 5th - 6th century. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. University of Central Lancashire, Grave 54, 1346

This complete pot was the only artefact found in the infant's grave. Anglo-Saxon, 5th - 6th century. Oakington, Cambridegshire. University of Central Lancashire, Grave 65, 1442

This complete pot was the only artefact found in the infant's grave. Anglo-Saxon, 5th - 6th century. Oakington, Cambridegshire. University of Central Lancashire, Grave 65, 1442

This infant's burial contained a single pot but no other grave goods. Anglo-Saxon, 5th - 6th century. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. University of Central Lancashire, Grave 68, 1459

This infant's burial contained a single pot but no other grave goods. Anglo-Saxon, 5th - 6th century. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. University of Central Lancashire, Grave 68, 1459

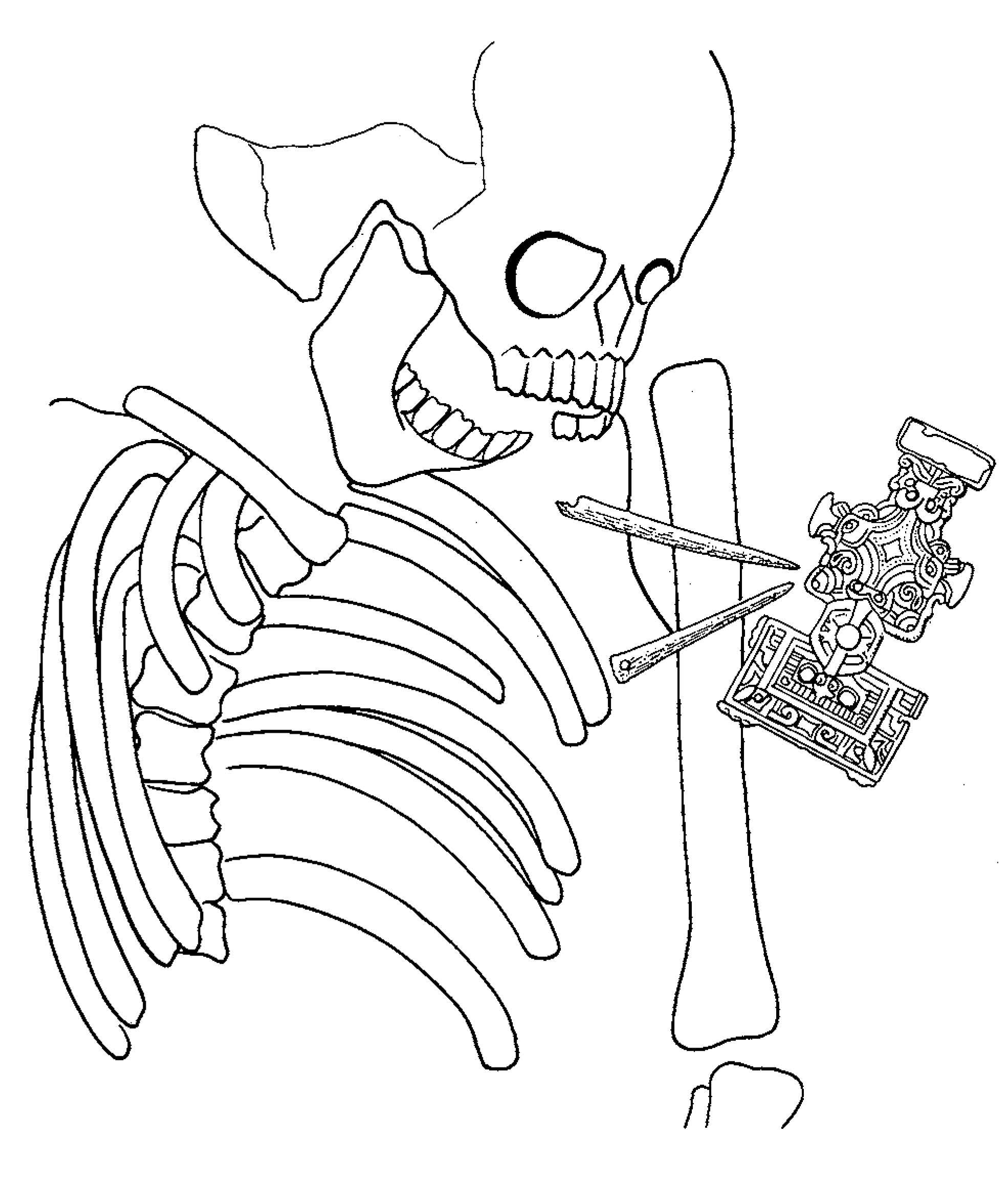

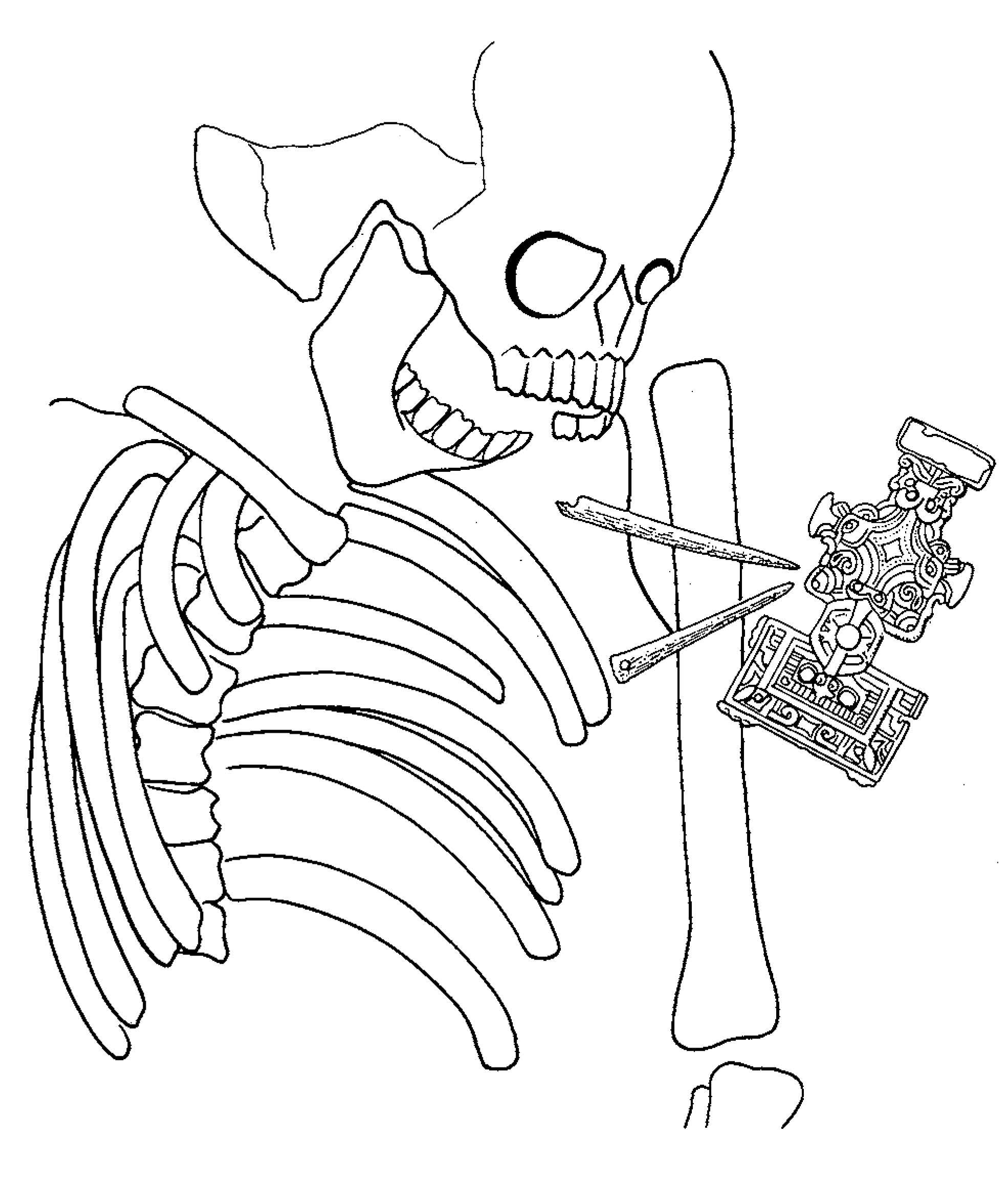

Questioning Adulthood

The remains of a teenage girl, aged between twelve and fifteen years old, were excavated with some of the finest grave goods found at the Oakington cemetery. The brooch and bone pins found in her grave comprise a set of dress accessories commonly associated with adult women.

Today we would not consider her an adult. Evidence suggests that the Anglo-Saxons believed otherwise. Lawcodes and grave goods found with adolescents show the transition to adulthood in this period was between the ages of twelve to fifteen. By setting aside our own preconceptions, we can enrich our understanding of the lives of children - and adults - in the past.

The image further below contains human remains, and is the final object slide in this virtual exhibition. Click on 'Looking to the Future' in the header bar to skip past this section.

Illustration by Linda Meadows, reproduced from the Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society with the kind permission of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society

Illustration by Linda Meadows, reproduced from the Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society with the kind permission of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society

Two perforated bone pins positioned at the neck or shoulders that were used to pin her dress together. Anglo-Saxon, c. AD 500-570 CE. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire County Council, OAKQW94 SK22 SF2-3.

Two perforated bone pins positioned at the neck or shoulders that were used to pin her dress together. Anglo-Saxon, c. AD 500-570 CE. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire County Council, OAKQW94 SK22 SF2-3.

Brooch made from gilded bronze with silver plating. It is beautifully decorated with intricate designs of stylised animals, beasts and human-like faces. Anglo-Saxon, 500 - 570 CE. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire County Council, OAKQW94 SK22 SF1

Brooch made from gilded bronze with silver plating. It is beautifully decorated with intricate designs of stylised animals, beasts and human-like faces. Anglo-Saxon, 500 - 570 CE. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. Cambridgeshire County Council, OAKQW94 SK22 SF1

Skeleton of a girl aged 12-15 years old. The discolouration on her left arm was caused by contact with the bronze brooch. Anglo-Saxon, 500 - 570 CE. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. University of Central Lancashire, OAKQW94 SK22

Skeleton of a girl aged 12-15 years old. The discolouration on her left arm was caused by contact with the bronze brooch. Anglo-Saxon, 500 - 570 CE. Oakington, Cambridgeshire. University of Central Lancashire, OAKQW94 SK22

Looking to the Future

Our understanding of children's lives in the past continues to develop. On-going research, new discoveries, and excavations are uncovering information to challenge previous interpretations.

By asking different questions, and using some imagination, archaeologists are moving away from looking at the ancient world exclusively through adult eyes. They are now actively looking for children and investigating their impact on past stories.

Each new discovery can only enrich our understanding of what life was like for children in the past.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Heritage Lottery Fund for funding this exhibition.

We would also like to thank our lenders and the members of our consultation and advisory panels who gave us invaluable support and encouragement throughout the project.