Woven Histories

This virtual exhibition re-presents objects from the University of Cambridge Museums in works created by artists as part of the Museum Remix: Unheard project.

Here, to introduce it, is your host, guest curator Lucian Stephenson. Lucian is a Cambridge-based illustrator and craftsman, a volunteer tour guide at the Museum of Classical Archaeology, and a friend of the Museum Remix project since 2019.

Definitions of disability

Katy Whitaker's eight-page zine, or mini magazine, is made from a single sheet of A4 paper.

Here is Lucian to introduce it.

Katy's zine was inspired by a pair of 18th-century spectacles at the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, and the questions they raise around definitions of disability, how these change over time, and who gets to make the definition.

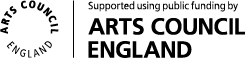

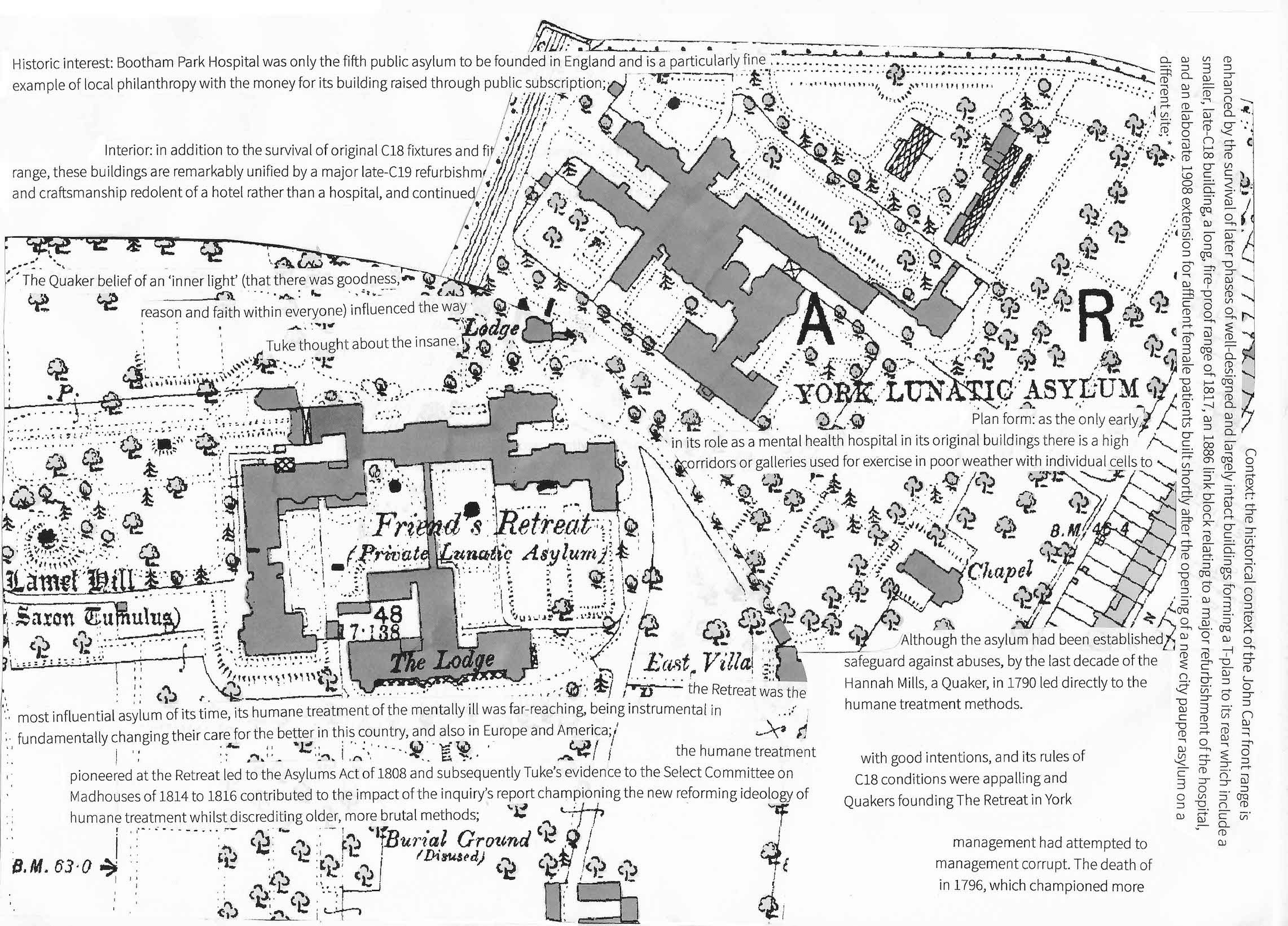

The zine is comprised of layers of a historical Ordnance Survey, text from Historic England's National Heritage List for England (seemingly "objective" and "official" records) and contrasts two institutions for patients with mental ill-health: one, York Asylum, with a terrible reputation, and the second, The Retreat, considered a model for the good treatment of patients.

Katy says,

"I cast my mind to the ways that mental health has been 'seen'. The institutionalisation of people with poor mental health, the institutions into which people were placed; and how that institutionalisation was and is perpetuated in other 'official' arenas. ...

The visual and textual language used on the old maps and in the more recent NHLE text descriptions of buildings is part of the definition-making around mental health. While apparently simply providing factual information about the institutions, the language used perpetuates stigma about poor mental health, like repeating the word 'insane' and talking about the perceived violence of patients."

Spectacles

Now in the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, these gold-rimmed spectacles are hinged at the bridge so they may be folded neatly away into their fishskin case. They date from around 1750 to 1800, before attitudes towards disability hardened around whether a person was able to work.

Sir John Finch

Sir Thomas Baines

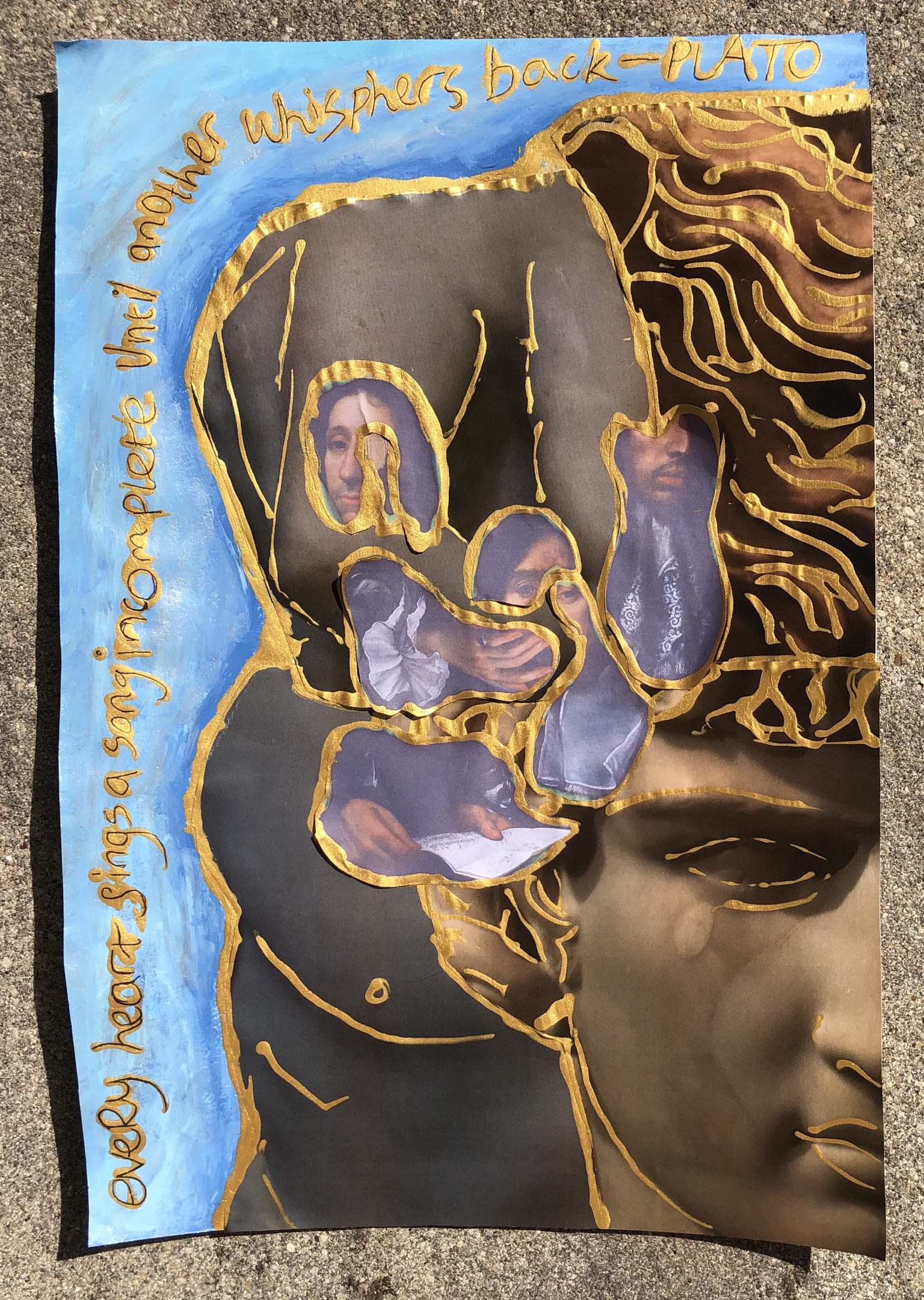

and A Song Incomplete

A Song Incomplete

by Thomas Chandler

Collage with paper and paint

Thomas Chandler's collage A Song Incomplete was inspired by portraits of Sir John Finch and Sir Thomas Baines by Carlo Dolci, in the Fitzwilliam Museum.

The collage overlays extracts from their portraits onto an ancient sculpture of Antinous, the lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian.

Lucian says, "The exploration of the piece is immediately obvious: the gold that edges the collage’s pieces, highlighting the observational beauty of the subjects (and thereby implying the desire of the artist) is staggeringly beautiful."

Finch & Baines

John Finch and Thomas Baines, both trained physicians, met while studying at Cambridge in the 1640s. They were inseparable throughout a relationship that lasted 36 years, and were buried together in a joint monument in Christ's College, Cambridge.

Finch commissioned the portraits from Carlo Dolci in 1665, during a diplomatic mission to Florence; he would later serve as British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Baines is shown reading books of philosophy - including Plato - demonstrating his wide-ranging interests.

Artist Thomas Chandler writes,

"I enjoyed the LGBT+ history behind the paintings. I approached it from my interest in classical and Renaissance art and modern re-interpretation of these as they are so often infused with homoerotic tension. I wanted a contrast between the explicit beauty of the sculpture and the implicit love between the portraits and the sitters. I believe the museums should make an effort approach queer objects in the context of other queer objects, rather than, as they often do, stripping objects back to style or period."

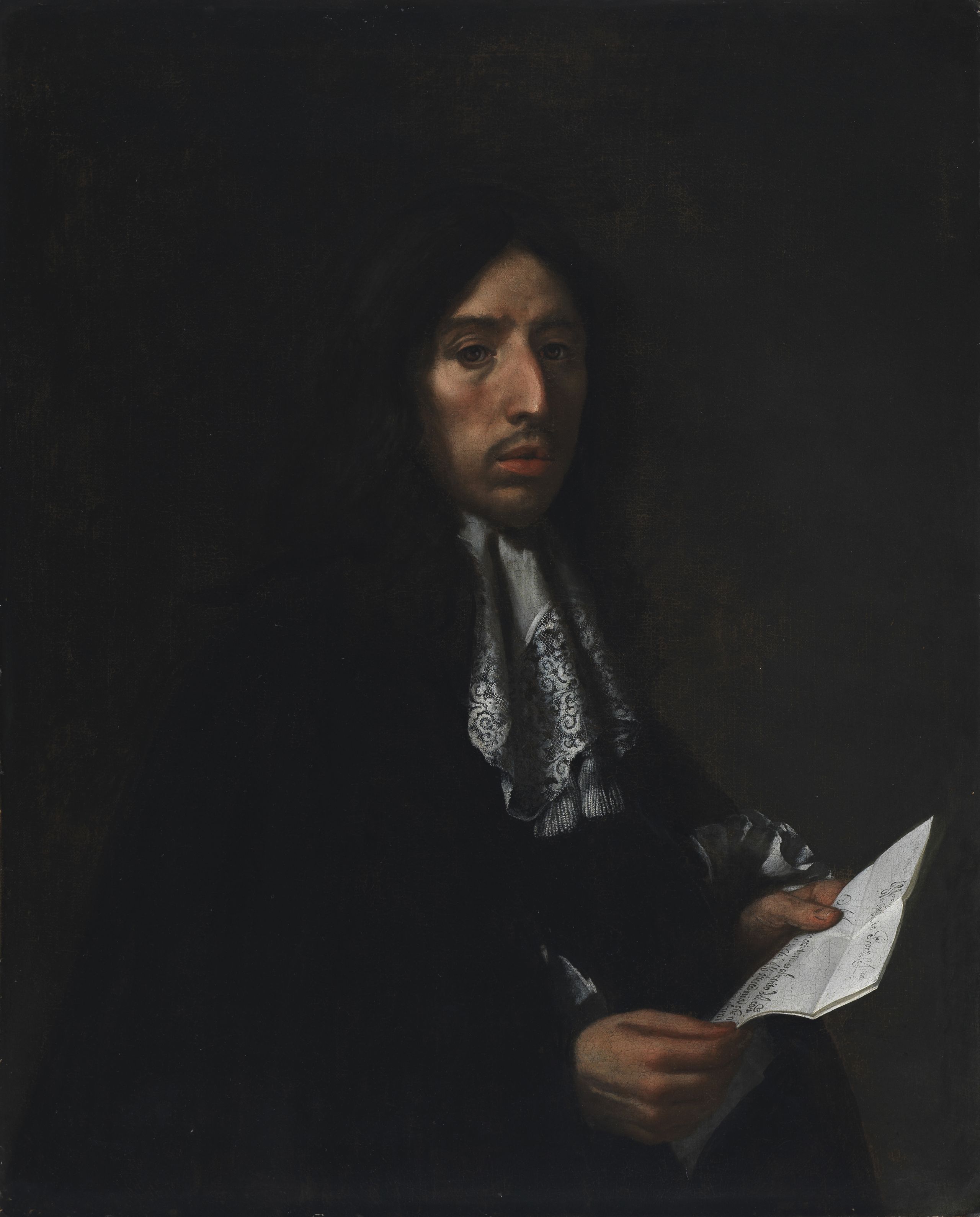

Carlo Dolci (1616-1686) Sir John Finch, c.1665-70 Oil on canvas

Carlo Dolci (1616-1686) Sir John Finch, c.1665-70 Oil on canvas

Carlo Dolci (1616-1686) Sir Thomas Baines c.1665-70 Oil on canvas

Carlo Dolci (1616-1686) Sir Thomas Baines c.1665-70 Oil on canvas

What is disability and why does it matter?

![A4 poster with colourful text against a white background, and images inset. The first section of text is in three columns. The writing is a different colour in each column. It reads: "What is disability and why does it matter? There are many different interpretations of disability. Maybe you think of this: [picture of a wheelchair]. But would you consider mild sight loss a disability? Before glasses were invented, it would have been considered so... [photo of gold-rimmed 18th century spectacles, with their small leather case] ... as anyone who has ever lost their glasses may agree with!" The second section of text is in two columns. It says, "However, blindness and severe sight loss cannot be cured with glasses, and can have a huge impact on people’s everyday lives. As do many “invisible” conditions, such as migraines, which often affect people’s sight during a migraine attack. Not to mention, the impact of “invisible disabilities” such as Multiple Sclerosis, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, Ehlers Danlos and many more. “Migraine-relief” glasses exist, which supposedly filter certain wavelengths of light to reduce eye pain– but are these genuine or just a gimmick? It can be hard to tell which products are actually going to help." [Photo of a pair of miraine relief glasses. They are large plastic glasses with dark lenses.] The final section of text runs along the bottom of the page. It says, "Next time you are in a museum, think about what items might have been used for and what type of society would create them. Did they help or hinder the people who needed to use them?"](./assets/HGnxWwT07O/what-is-disability-museum-remix-poster-z-sweetland-1-1-2288x3444.jpeg)

What is disability and why does it matter?

Zowie Sweetland

Poster

Zowie Sweetland's poster What is disability and why does it matter? is inspired by the 18th-century spectacles in the Whipple Museum of the History of Science.

Lucian says, "I loved the illustration of “invisible” disabilities through the “lens” (ho ho) of visual impairment, introducing the reader to disabilities that they might not be familiar with using the model of something that they will already understand. It worked perfectly."

Zowie says, "As someone with various disabilities, thinking about an object in terms of disability sounded appealing to raise awareness of "invisible disabilities."

Queen Victoria

in stolen clothes

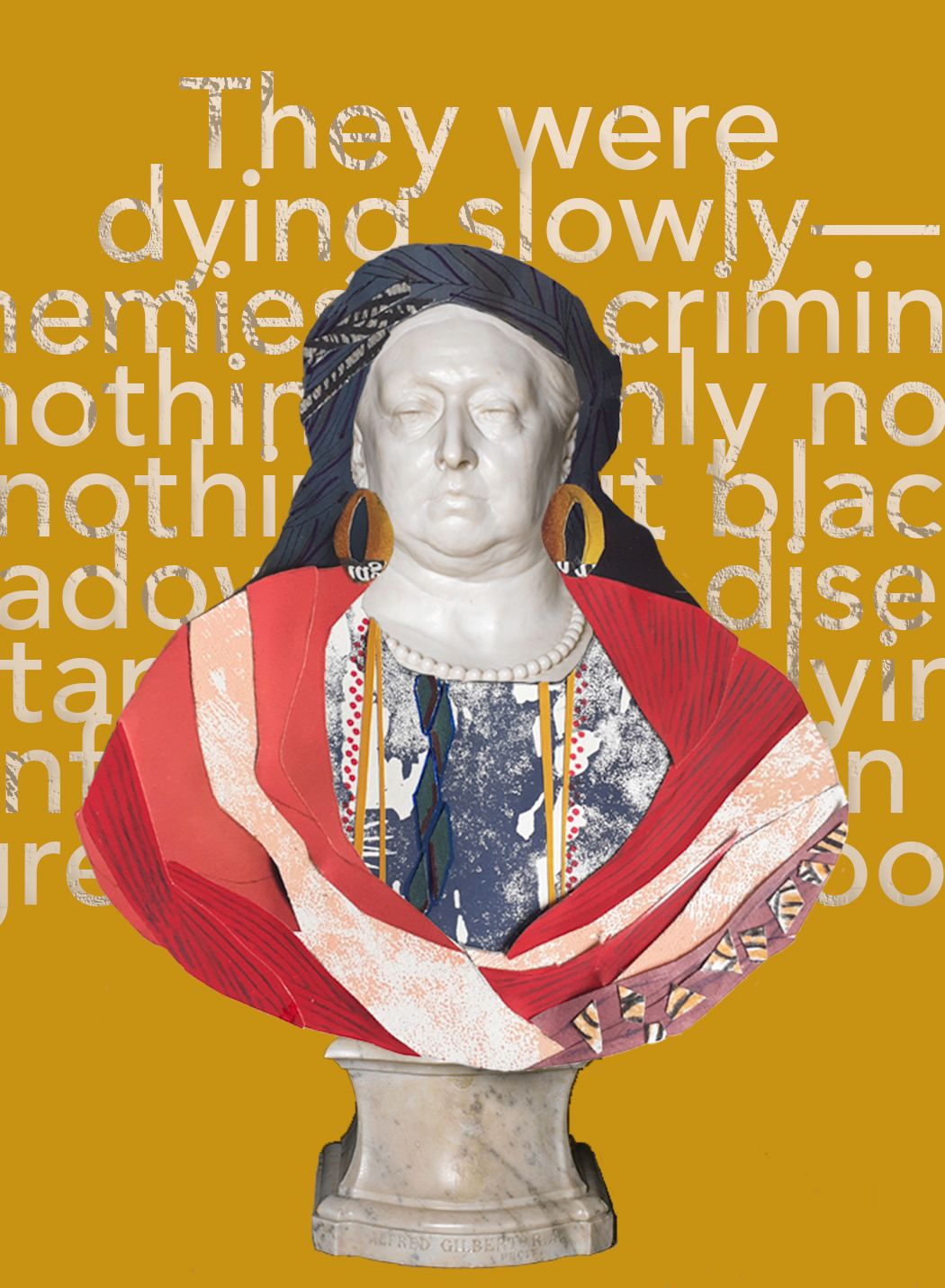

Queen V: the roots of cultural appropriation

Carole Bouvier

Collage with words from Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness

Carole Bouvier's digital collage is inspired by the Fitzwilliam Museum's bust of Queen Victoria. The collage dresses the Queen in patterns inspired by Nigerian fabrics in the collection of the Musee du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, and period photographs.

Lucian observes, "This work drew my attention immediately. ... It had a deep ominousness to it."

Queen Victoria

This larger-than-life portrait of Queen Victoria, ageing, careworn, and sad, was sculpted between 1887-1889 as she celebrated 50 years on the throne.

As a portrait of an obviously older, powerful woman (Victoria was aged 68), it's unusual in a museum gallery, where the walls are covered with young beauties. But she is also a powerful symbol of the British Empire. Portraits in museums allow us to think about who was celebrated in the past, and how our opinions of them may have changed over time. Given what we know about the enormous impact of the British Empire, the millions of deaths it caused and its ongoing impacts around the world, how should we respond to the sculpture? How should it be displayed?

Artist Carole Bouchier says, "What would queens and kings of that time have looked like if they had adopted some of the traditions of the countries they invaded? Would the term cultural appropriation have existed earlier?

One question in particular stayed with me and became the theme of this submission: would cultural appropriation exist without an initial denial of the very same culture?"

Sir Alfred Gilbert RA (1854–1934)

Bust of Queen Victoria (1819–1901)

England, London, 1887-9

White marble

Sir Alfred Gilbert RA (1854–1934)

Bust of Queen Victoria (1819–1901)

England, London, 1887-9

White marble

The Empress's plant

Josephina imperatricis

The next works in Lucian's selection are both inspired by a botanical watercolour in the Fitzwilliam Museum by Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

This plant isn't a humble nettle, but josephina imperatricis, named after Empress Joséphine, the wife of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Joséphine (1763-1843) filled the Malmaison Palace in Paris with exotic plants from the lands her husband Napoleon had conquered.

What can this botanical watercolour by tell us about the relationship between empire and science? Should Joséphine be considered a scientist in her own right?

Josephine Hybrid

by Helen Grundy

Digital collage

Helen Grundy's collage splices Redouté's watercolour of Josephina imperatricis with a portrait of its namesake, the Empress Joséphine.

Lucian says, "A completely beautiful, visually balanced, tightly designed piece, smashing together Empress Josephine and her plant."

Helen says, "I was drawn to the object as it was such a beautiful artwork in its own right, and I loved the accompanying information as I had no idea how much she loved plants. It inspired me to create a new piece of work."

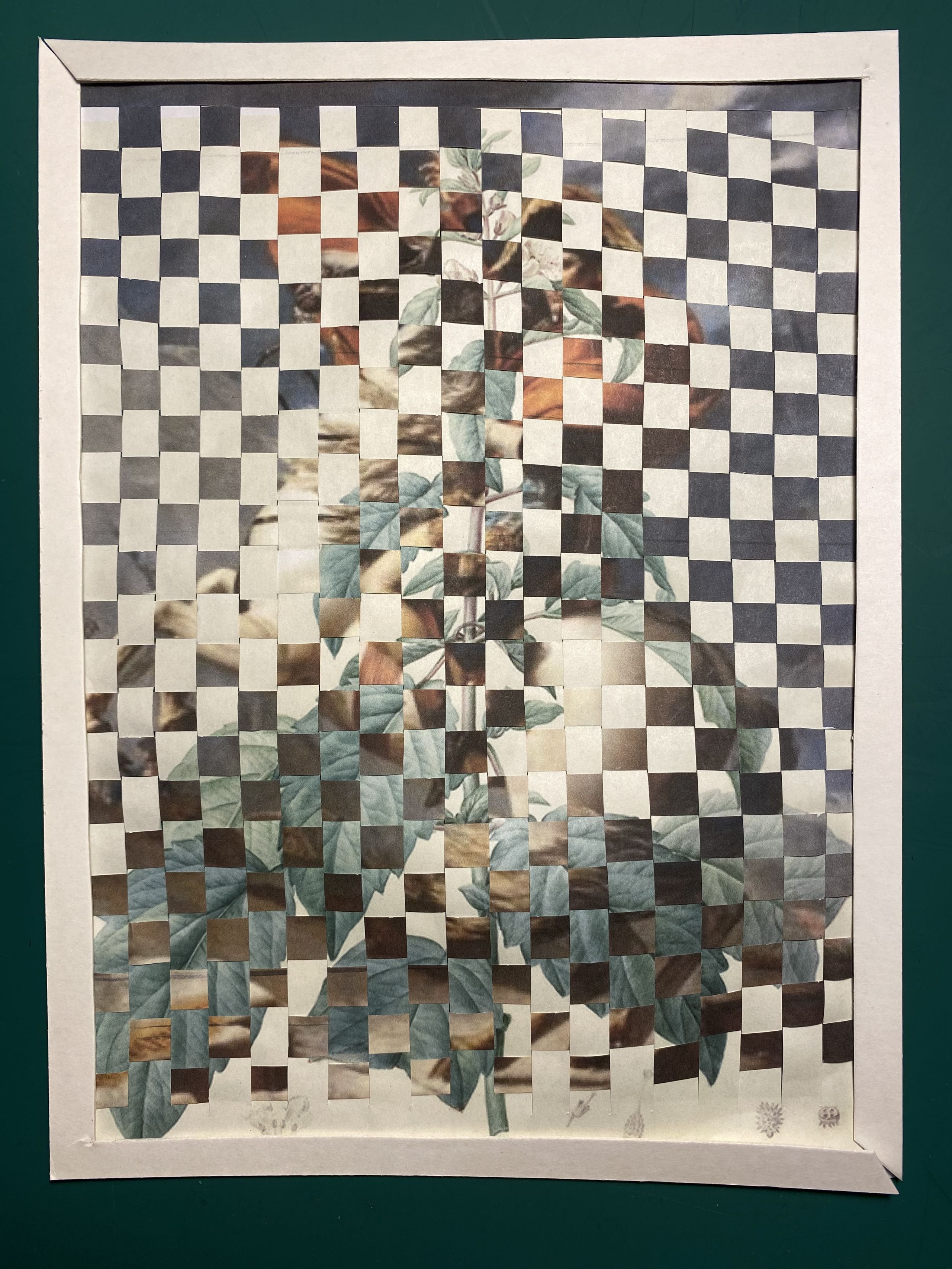

Woven Histories

by Claire O'Brien

Collage

Claire O'Brien has woven together Redouté's watercolour with Jacques-Louis David's portrait of Napoleon Crossing the Alps, now in the Malmaison Palace.

Lucian says, "It illustrates with razor precision the combined histories of botanical science and warfare, the voices that are heard and unheard, the uncomfortable marriage of discovery and bloodshed, and - as the artist says - “probably many more!”.

Claire says, "I liked the pyramidal structure of the plant and knew of the similar composition in the painting. ... Empress Josephine tended the floral specimens such as this, that arrived at Malmaison for her from around the world, and they were recorded by the greatest botanical artists of the day. This version of the painting of Napoleon now hangs at Malmaison. The existence and histories of the two images are woven together.

The more 'back stories' we can learn about objects in museums, the richer the experience and greater understanding we can apply to our lives in the present. This story is about conquest, commodity, cultural exchange, theft, the natural world, science and human ingenuity, and art...and probably more!"

The best of the rest

Female Power by Victoria Chong, inspired by the plaster cast of a woman elbowing a centaur on the pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, in the Museum of Classical Archaeology. Digital painting. Victoria says, "This object appeals to me as I feel that especially in light of the Me Too era it is vital to listen and represent the female perspective which has for too long been disregarded. It is quite rare to see a women defending herself in historical artifacts as well." Lucian says, "It’s very competently executed, gorgeous to look at and very beautifully composed. Good colours, too."

Female Power by Victoria Chong, inspired by the plaster cast of a woman elbowing a centaur on the pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, in the Museum of Classical Archaeology. Digital painting. Victoria says, "This object appeals to me as I feel that especially in light of the Me Too era it is vital to listen and represent the female perspective which has for too long been disregarded. It is quite rare to see a women defending herself in historical artifacts as well." Lucian says, "It’s very competently executed, gorgeous to look at and very beautifully composed. Good colours, too."

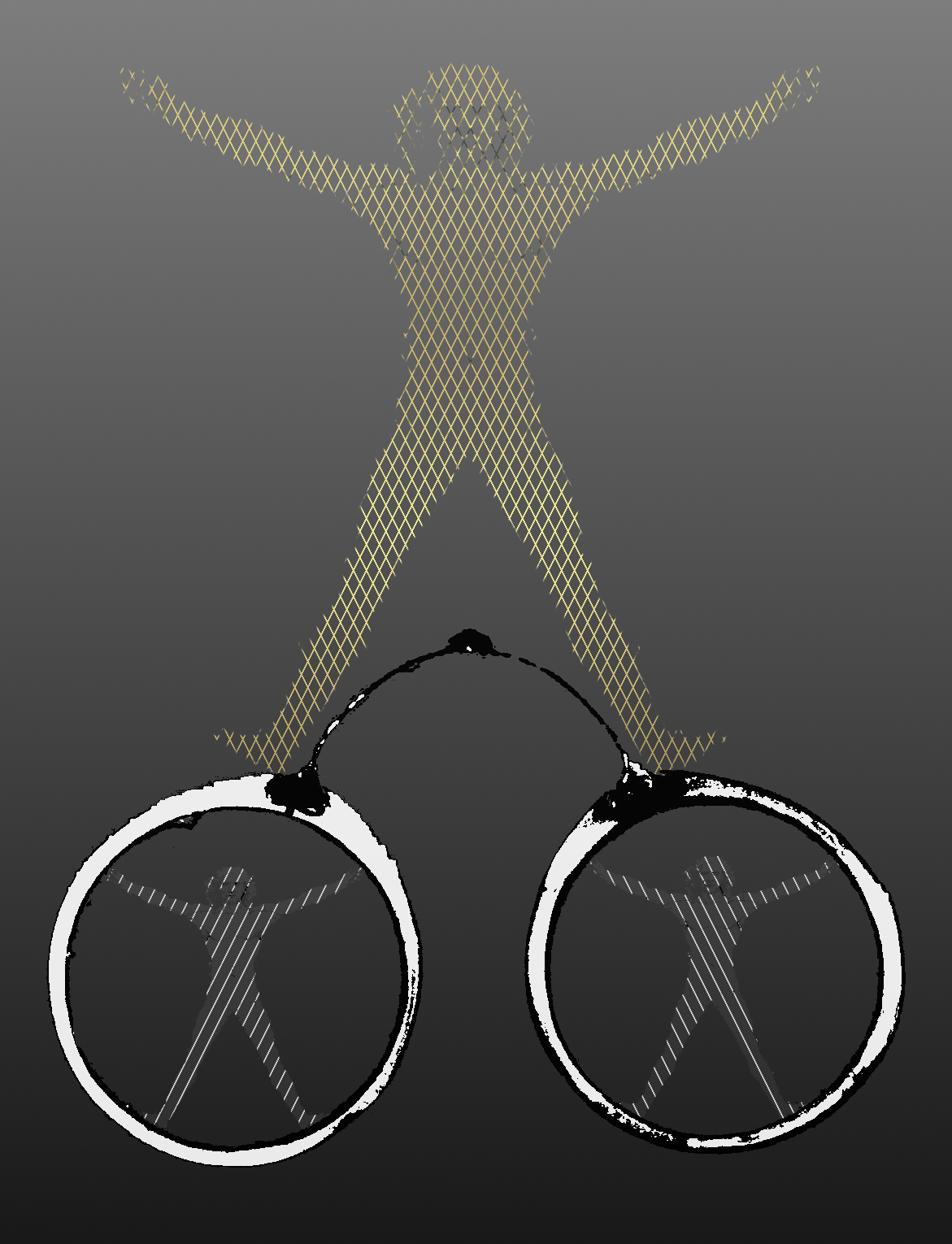

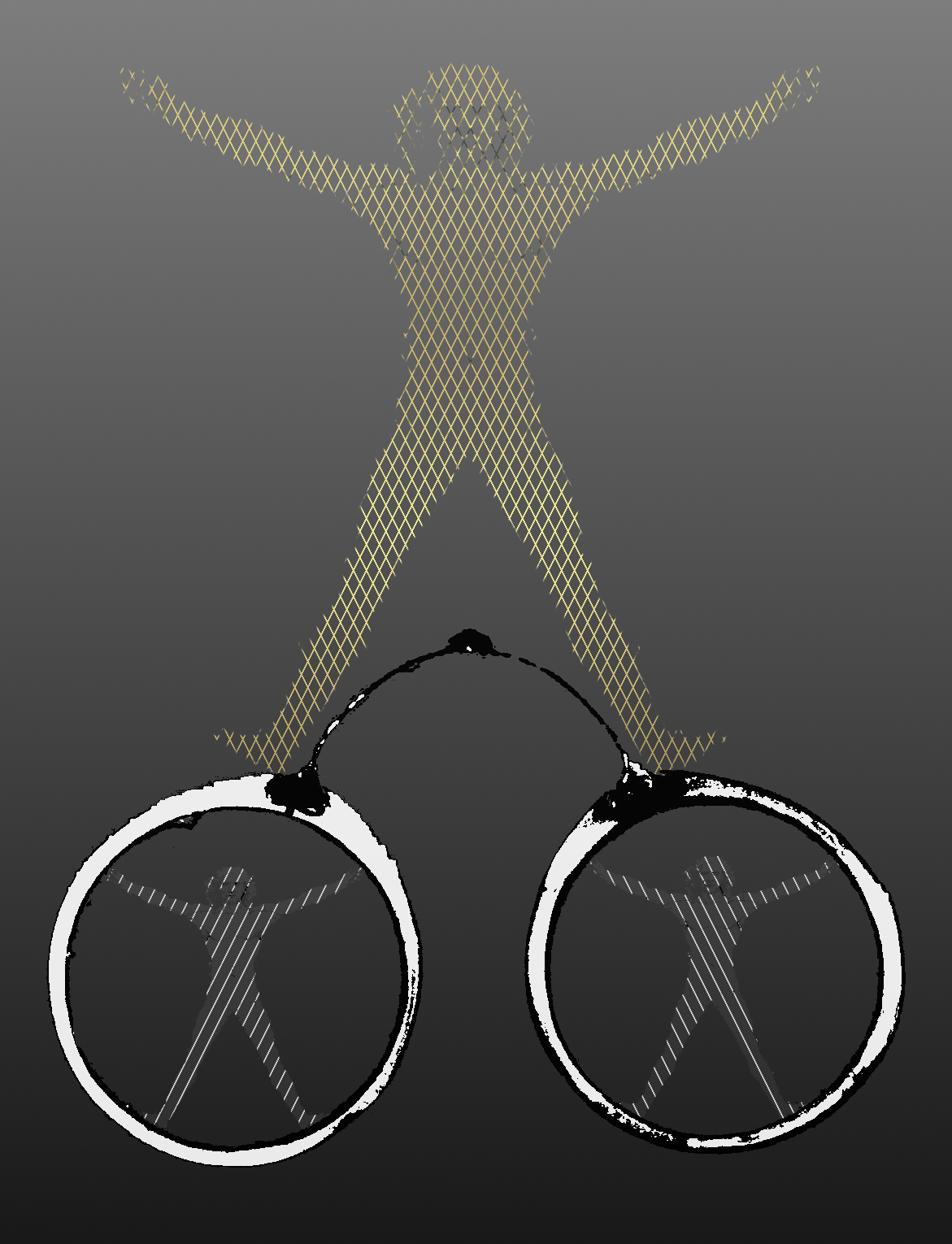

Vitruvius 2.0 by Steven Goodwin: composite digital image using a stylised version of Leonardo Da Vinci's Vitruvian Man. Steven says, "Through one lens you see the shape of a human composed only of rising diagonal lines, depicting the increasing reliance on implants used to overcome our disabilities. Through the other we see falling lines, showing that our temporarily able body disappears over time. Only when we accept that we are all natural cyborgs, part human, part technology, can both sides be combined into the whole, as shown at the top. Glasses are the first piece of wearable technology I needed to overcome a disability, so were a natural fit to being able to present the core idea: that is, each person is a cyborg and neither the person (nor the tech) should be considered a disability." Lucian says, "The image would look fantastic blown up to huge, with accompanying text, but I can’t help but feel that it would benefit more from an interactive presentation - perhaps where the viewer dons spectacles themselves to see the new Vitruvian Man, a natural cyborg, neither disabled by the natural decay of their body nor by society’s marginalisation of their access needs, and therein see themselves reflected."

Vitruvius 2.0 by Steven Goodwin: composite digital image using a stylised version of Leonardo Da Vinci's Vitruvian Man. Steven says, "Through one lens you see the shape of a human composed only of rising diagonal lines, depicting the increasing reliance on implants used to overcome our disabilities. Through the other we see falling lines, showing that our temporarily able body disappears over time. Only when we accept that we are all natural cyborgs, part human, part technology, can both sides be combined into the whole, as shown at the top. Glasses are the first piece of wearable technology I needed to overcome a disability, so were a natural fit to being able to present the core idea: that is, each person is a cyborg and neither the person (nor the tech) should be considered a disability." Lucian says, "The image would look fantastic blown up to huge, with accompanying text, but I can’t help but feel that it would benefit more from an interactive presentation - perhaps where the viewer dons spectacles themselves to see the new Vitruvian Man, a natural cyborg, neither disabled by the natural decay of their body nor by society’s marginalisation of their access needs, and therein see themselves reflected."

The Queen of Sheba by Julien Masson, inspired by all the Museum Remix objects. Julien says, "I am trying to represent the multicultural aspects of contemporary culture and how individuals define and shape their own personal identities. I believe, it is a process that has been very much accelerated by the prevalent use of digital technology." Lucian says, "A very competently rendered, beautifully balanced digital collage, compositing various objects from the Remix into a figure that evokes the “stereotypical” white alabaster bust of a classical history museum, while reflecting a variety of different viewers, topics and perspectives ."

The Queen of Sheba by Julien Masson, inspired by all the Museum Remix objects. Julien says, "I am trying to represent the multicultural aspects of contemporary culture and how individuals define and shape their own personal identities. I believe, it is a process that has been very much accelerated by the prevalent use of digital technology." Lucian says, "A very competently rendered, beautifully balanced digital collage, compositing various objects from the Remix into a figure that evokes the “stereotypical” white alabaster bust of a classical history museum, while reflecting a variety of different viewers, topics and perspectives ."

Frozen Footsteps by Rosie Wright, inspired by Phyllis Wager's Typewriter in the Polar Museum. Rosie says, "The collage aims to explore the physical and written traces of Arctic exploration, challenge the way we choose to frame this unique environment and ask how we can reuse words, art and stories to make different choices visible. " Lucian says, " I do see and understand the “masculine” assertion of architectural remnants as a narrative of dominance and conquest on the fragile Arctic landscape without care or heed of the flora, fauna and Indigenous people who live there, and think this is a vital thing to explore."

Frozen Footsteps by Rosie Wright, inspired by Phyllis Wager's Typewriter in the Polar Museum. Rosie says, "The collage aims to explore the physical and written traces of Arctic exploration, challenge the way we choose to frame this unique environment and ask how we can reuse words, art and stories to make different choices visible. " Lucian says, " I do see and understand the “masculine” assertion of architectural remnants as a narrative of dominance and conquest on the fragile Arctic landscape without care or heed of the flora, fauna and Indigenous people who live there, and think this is a vital thing to explore."

This exhibition was produced as part of the University of Cambridge Museums' Museum Remix: Unheard project in August 2020.

With grateful thanks to:

Lucian Stephenson

Katy Whitaker

Thomas Chandler

Zowie Sweetland

Carole Bouvier

Helen Grundy

Claire O'Brien

Victoria Chong

Steven Goodwin

Julien Masson

Rosie Wright

and staff from across the University of Cambridge Museums.