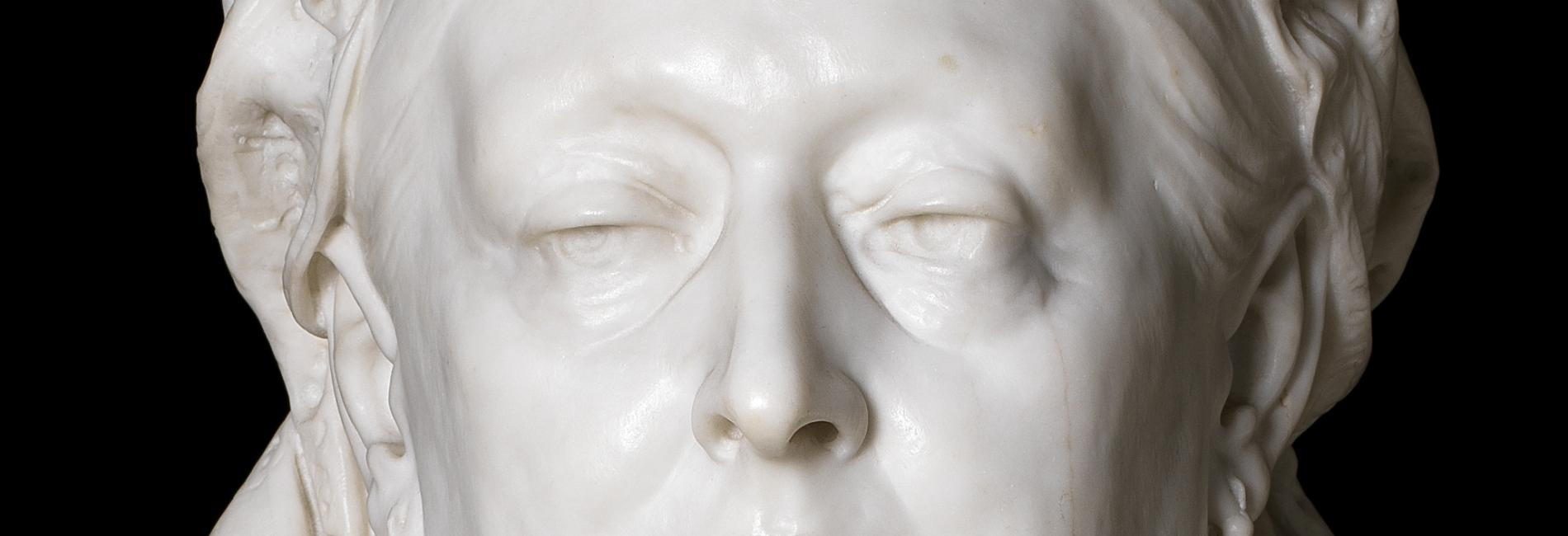

This larger-than-life portrait of Queen Victoria, ageing, careworn, and sad, was sculpted between 1887-1889 as she celebrated 50 years on the throne.

As a portrait of an obviously older, powerful woman (Victoria was aged 68), it's unusual in a museum gallery, where the walls are covered with young beauties. But she is also a powerful symbol of the British Empire. Portraits in museums allow us to think about who was celebrated in the past, and how our opinions of them may have changed over time. Given what we know about the enormous impact of the British Empire, the millions of deaths it caused and its ongoing impacts around the world, how should we respond to the sculpture? How should it be displayed?

Helen Ritchie, curator at the Fitzwilliam Museum, tells us more.

More information

The sculpture

Close up view of Queen Victoria's face

The sculpture's label

The sculpture is accompanied in the gallery by this label text, written in June 2018:

Sir Alfred Gilbert RA (1854–1934)

Bust of Queen Victoria (1819–1901)

England, London, 1887-9

White marble

Signed: ALFRED GILBERT RA / FECIT (Alfred Gilbert, Royal Academician made this)

Purchased with funds from the Hartley-Johnson Bequest, the National Heritage Memorial Fund and private donations

M.1-2018

This monumental and majestic bust was commissioned by The Army and Navy Club in 1887 to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee and the club’s own fiftieth anniversary. It was carved single-handedly by Alfred Gilbert, whose most famous work is ‘Eros' in Piccadilly Circus (1886–93).

The virtuoso rendering of the different textures of skin, hair, drapery and jewellery is unparalleled in nineteenth-century British sculpture, as is the empathetic carving of the sad, careworn and introverted expression of the ageing monarch, whose Jubilee also marked her return to public life after a period of prolonged mourning for Prince Albert, who had died 1861.

Although the bust appears highly naturalistic, Gilbert did not work from the life but entirely from photographs, using his own mother as a model for the drapery, saying at the time: “One was Queen of my country – the other Queen of my heart.”

Gilbert originally made a metal crown for the bust, but then decided against using it. Although he promised to make a replacement in marble, he never did, and this explains why the Queen is shown, most unusually, without a crown, and why there are three small holes drilled into the top of her head.

Acquisition

The sculpture became part of the Fitzwilliam Museum's collection in June 2018. You can download the original press release here.

Photographs of Queen Victoria

These photographs of Queen Victoria were used by the sculptor Alfred Gilbert as the basis for the work. They were taken to commemorate the Queen's Golden Jubilee.