How would you change one of our museums to tell stories about climate change? That was the question we posed to 24 people who participated in our first ever Climate Hack.

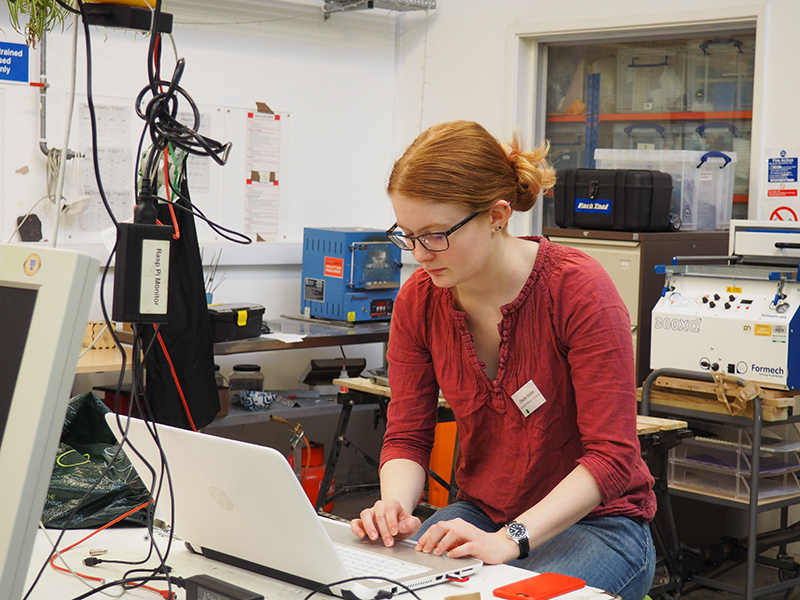

The premise was simple. Over three days we challenged four teams to make a prototype exhibit or display to be installed in one of our museums: the Polar Museum, the Museum of Zoology, the Whipple Museum of the History of Science and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA). Each team had a combination of skilled makers and artists, people who know all about audiences and somebody with a good understanding of environmental science or the impact of climate change on different people. With the fantastic facilities of the Cambridge Makespace as our base, there were lots of possibilities and we had no idea what the teams would come up with. Handing over control of what goes into our museums was both a little frightening and very exciting, especially as we were inviting the public in to the museums to see the teams’ final creations.

Day one was all about getting to know each other, the museums and our visitors. Research with visitors shows that museums are one of the most trusted sources of information about climate change. Nevertheless, the topic remains confusing for many people with dense layers of information to navigate. Each team got to meet experts at their museum and spent some time debating what they might make and install. This was important, because at 10.30 on day two they would be pitching their ideas to everybody else.

Some teams got themselves off to a very early start on day 2, meeting up in the Makespace to discuss their final ideas. All the hard work paid dividends; the groups had come up with some fantastic ideas. Now they just needed to put them into action – it was time to start making!

What did the teams come up with?

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

The MAA team had learnt about Kiribati, a country in the Pacific Ocean which is made up of a series of islands. Sea level rise is already affecting the residents of Kiribati, and models suggest that climate change could make the islands uninhabitable within a century. Some islanders have already moved away from the islands as a result of changing weather patterns and floods. The team focused on the idea of flooding, and decided that their exhibit would share stories of flooding and migration in Kiribati, but also in the fens around Cambridgeshire. Inspired by ‘ghost nets’, they built a ‘ghost boat’ in which stories and links to stories were entangled. Visitors to the exhibit would also be invited to share their own stories, and make a paper boat in which they could write down what they would save in a flood. You can find out more about the project in a blog post written by Bridget McKenzie, one of the team members, including links to some of those fantastic flood stories.

Whipple Museum

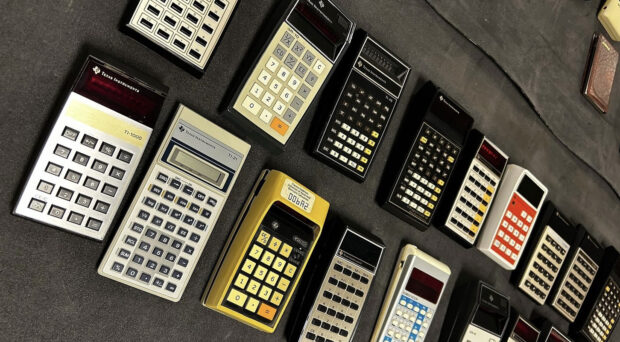

The audience research we’d shared with the teams suggested that many people were interested in the long history of how we understand our climate. The Whipple Museum team decided to use this, and built an interactive exhibit that explored how a Campbell-Stokes sunshine recorder worked. They were able to install their exhibit next to the Museum’s example of the recorder, and give visitors the opportunity get hands on and learn about how recording hours of sunshine over many years is just one way that we have built up an understanding of our environment. The final part of the exhibit was a model of a satellite paired with a short film to explain how scientists today are taking a more direct approach to studying the sun.

Museum of Zoology

While the Museum of Zoology is closed for refurbishment, its Whale Hall is open on Friday and Saturday afternoons. The team based there had a very open space to make use of and installed a couple of experiences. One was a hands-on activity which invited people to physically ‘capture’ some carbon and other greenhouse gases while learning about what that meant. A second installation was inspired by the Holme Post, a cast iron post that shows how much peat has shrunk since the draining of Whittlesea Mere. The team made their own post, which was also a listening post. Visitors could plug in headphones to listen to audio about changing landscapes and environments over time. They were also invited to think about how we use timelines for helping us to understand changing climate, and had the opportunity to draw their own timeline or leave their own stories to add to the post.

Polar Museum

In the Polar Museum, stories about climate change are almost always about changes in ice. The team installed a two-part exhibit. In the entrance hall, visitors were able to see a projection of sea ice on the beautiful painted map of the Arctic that is on the museum’s ceiling. By turning a dial they could change which year they were looking at, or by turning a second dial they could vary the month. With data going back 150 years this helped visitors to see just how much ice has changed over time. Moving into the main museum, visitors could follow a family friendly trail that took them around the Northwest Passage, a shipping route now open to tourism and commercial shipping because there is less ice than there used to be. Along the way they met tourists, scientists and Inuit people and encountered some of the challenges and opportunities brought about by the reduction in ice.

Lots to think about

The prototypes were filled with fantastic ideas, and gave us and our visitors lots to think about. Feedback from visitors showed that exploring climate change in our museums offered a different way to think about its impacts. Several of the comments left by visitors suggested that using narratives and stepping outside of a strictly scientific context for talking about climate change helped and inspired them. For us at the University of Cambridge Museums it was a privilege to be able to hand over the reins to the teams and give somebody else the chance to decide how we tackle difficult and important issues in our museums. We learnt a lot about running this kind of event, and I very much hope that this is something we will do more often – especially after the great success of Climate Hack 2018.