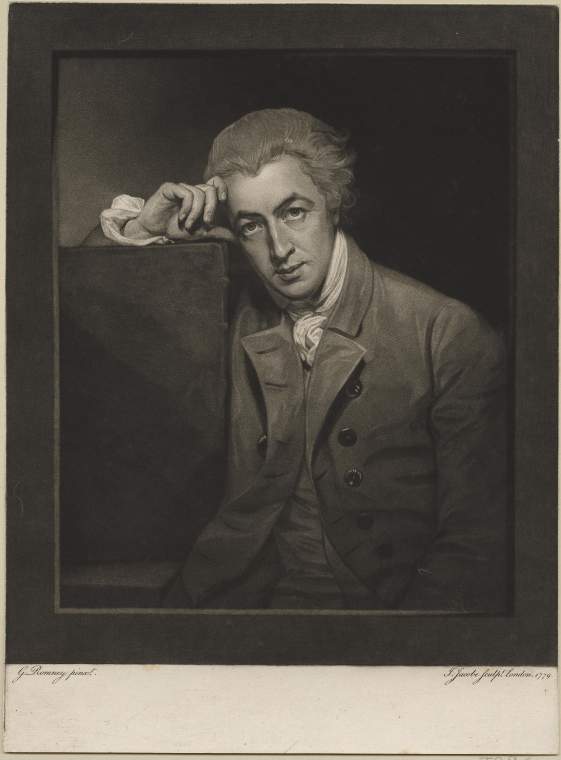

William Hayley (1745-1820) is a neglected figure whose influence on literary and cultural history is now being recognised. But who was he? Dr Lisa Gee has been researching and cataloguing the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Hayley Papers.

The Fitzwilliam Museum holds the world’s largest collection of manuscript material relating to William Hayley (1745-1820). But who was he? A largely unknown figure today, Hayley was an acclaimed poet, a multi-lingual scholar and the author of the bestselling and highly influential The Triumphs of Temper (which advised young women on how to attract and keep a husband and was written in rhyming couplets). He achieved both commercial and critical success before, towards the end of his life, his work fell out of fashion. Posthumously, he became a laughing-stock, remembered only for irritating William Blake and writing bad poetry. But who was he really?

Painting, pensions & the poet laureateship

Hayley was the first person to publish an extensive translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in English, a great friend of the artist George Romney, who for many years spent several weeks each summer with Hayley, relaxing and painting, and successfully lobbied the government to award the poet William Cowper a pension. Hayley also tried – with somewhat less success – to cure Cowper of “his calamitous depression”. And he negotiated book contracts for the poet and novelist Charlotte Smith. In 1790, Hayley was offered the poet laureateship, which he turned down, citing a combination of poor health and political objections to the duties attached to the post.

Saving William Blake

But today, where he’s known at all, it’s as the interfering patron of William Blake. The pair – one a successful author, the other a struggling engraver – met through their mutual friend, the sculptor John Flaxman. Late in the summer of 1800, Blake and his wife Catherine moved down to Felpham in West Sussex to collaborate with Hayley on engravings for his biography of Cowper. At first, Blake was delighted both with Felpham, and with Hayley. But, over time, the relationship deteriorated. Hayley was accustomed to advising his friends – including Cowper, Romney and the sculptor John Flaxman, through whom he met Blake – on subjects for their poetry and art. As this snarky verse in his notebook makes clear, Blake appreciated Hayley’s interventions rather less:

On Hayley’s Friendship

When Hayley finds out what you cannot do,

That is the very thing he’ll set you to;

If you break not your neck, ‘tis not his fault;

But pecks of poison are not pecks of salt.

Their relationship was, however, complex. And although Blake undoubtedly found his employer frustratingly overbearing and earthbound, he also learned a great deal from him. As well as paying Blake for his work, Hayley taught him Greek and expanded his knowledge of Milton. Blake was also hugely grateful for Hayley’s interventions when he was accused of sedition. Hayley helped post bail, organised and funded a lawyer, and spoke for Blake in court. It was, in fact, a large part, down to Hayley’s involvement that Blake was acquitted, escaping prison and a hefty fine.

But it’s not only for his Blake connection that Hayley matters. As the manuscripts in the Fitzwilliam Museum’s collection reveal, he was a significant mover and shaker in late eighteenth-century cultural life, someone whose published writings and correspondence reveal much about literary and artistic production and relationships in the late eighteenth century.

Look out for further posts on the Hayley Papers.