A new temporary display at the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences showcases the work of scientist Dr Emily Mitchell. Emily, a Henslow Research Fellow based in the Department of Earth Sciences, studies fossils of some of the very oldest and strangest animals found in remote locations in Newfoundland.

Museum Director Liz Hide had a chat with Emily, and with exhibition coordinator Rob Theodore from the Sedgwick Museum.

Emily, can you tell us a bit about where these fossils are found, and how you study them?

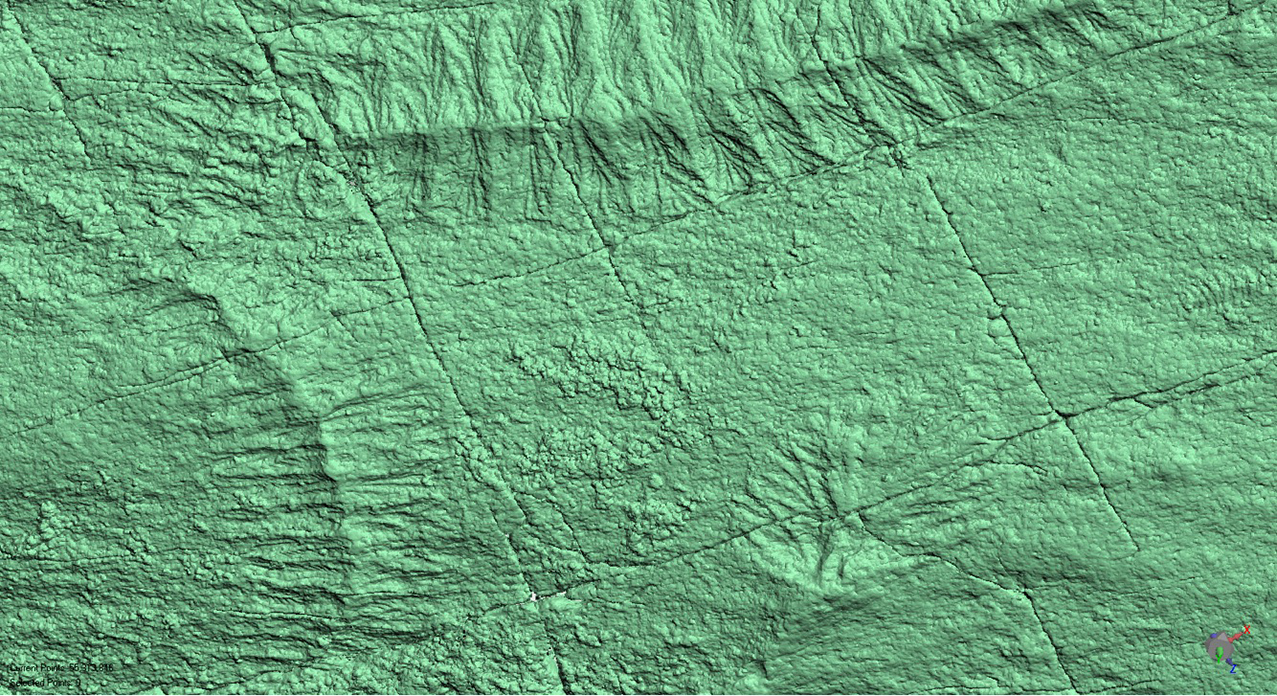

These fossil are found in rocks that are 580 million years old, on the coast in Newfoundland in Canada. Whole communities of these fossils are preserved right in the place that they lived and died – their position on the rock encapsulates their entire life history. They are in a remote location and, because of the weather, there are only 3-4 months in the year that we can get to study them. We can’t bring them back to the lab to study them so I scanned them using a handheld laser scanner – the same technique that is used to identify hairline fractures in Formula 1 cars – and reconstructed them digitally back in Cambridge.

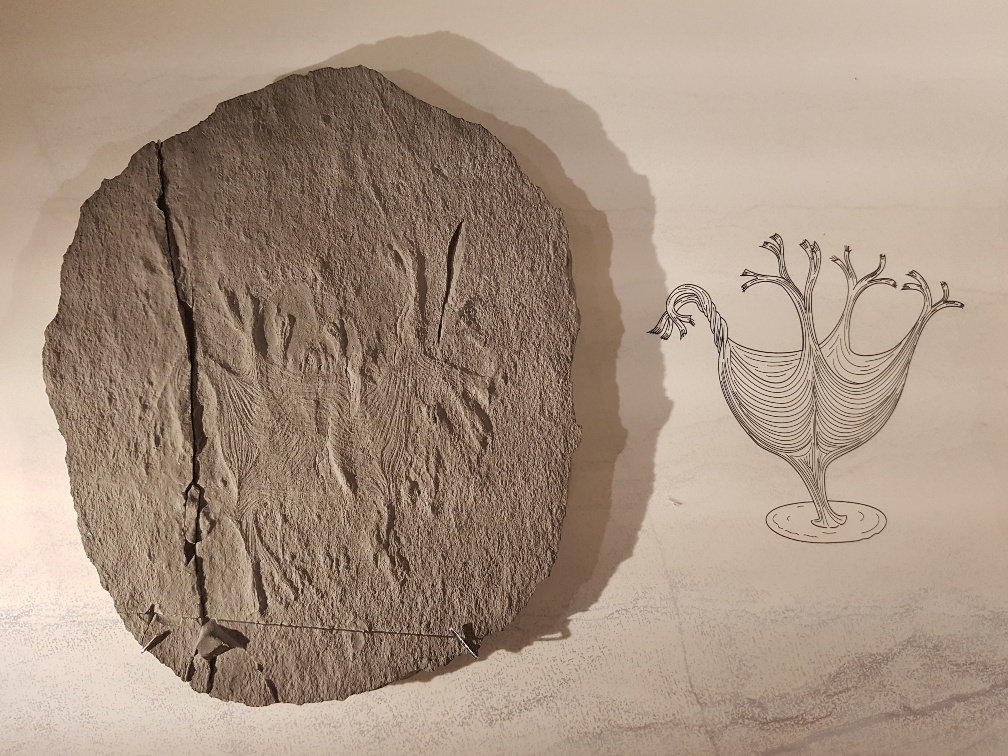

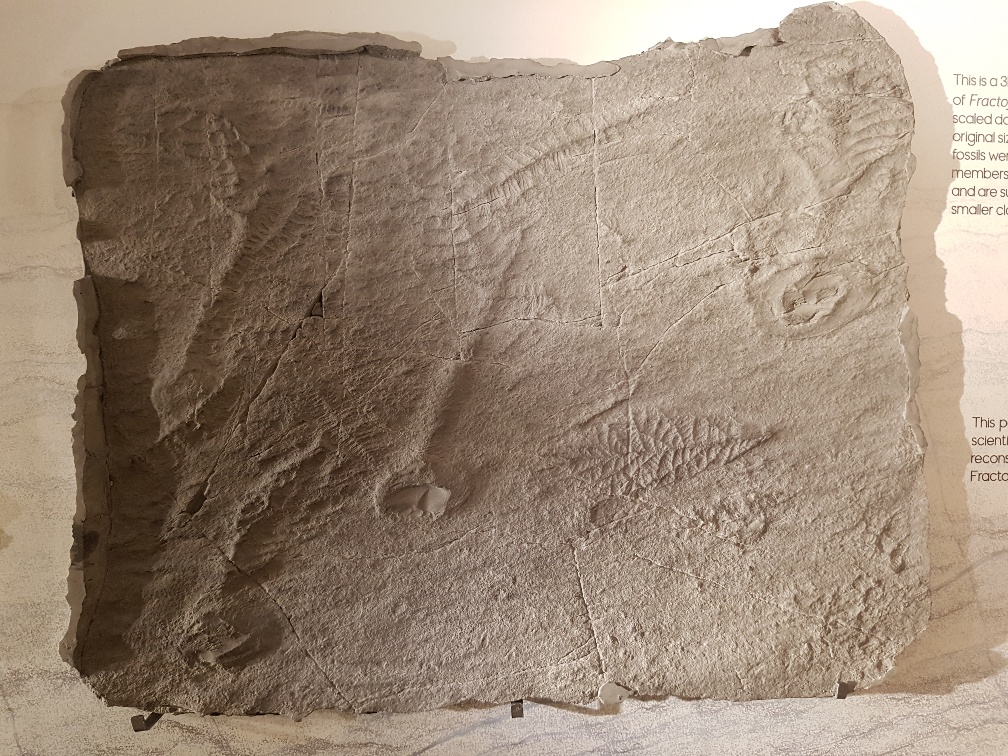

In the exhibition we have 3D prints of these scans and also have casts that we have made using from rubber moulds taken in the field.

Why do you think it’s so important to study these fossils?

These are some of the oldest animals on earth, so if we want to study animal evolution and where we came from, we need to understand these fossils.

Can you tell us about one of your most exciting finds?

My statistical analyses suggested that a species was reproducing asexually using stolons or runner. My colleagues then found actual fossil evidence of these stolon or filaments, providing physical evidence of these statistical analyses.

Any sticky moments doing fieldwork in such a remote location?

Two summers ago we were packing up at the end of the day, after collecting a huge amount of data. I’d just put the laptop away in its case and then it slide down a 30m cliff into in the sea. Fortunately, we managed to fish it out, dry it off and all the data was safe

Rob, tell us a bit about why you are keen to showcase Emily’s research in the Museum?

It is currently an exciting time for the Ediacaran research community. Studies are making their way into top journals and onto the mainstream news. Emily and her colleagues Drs Alex Liu and Charlotte Kenchington in the Ediacaran research group here at Cambridge are making key contributions to this. The museum is lucky to have this wonderful opportunity with scientists like Emily so keen to engage our visitors with their cutting-edge research.

What was it like working with these unusual specimens?

These specimens are beautiful, but also a bit weird! It can also be challenging to pick out and appreciate the fossils due to their low relief. To help our visitors understand what they are looking at, we layered reconstructions of the organisms and diagrams of the casts into our interpretation, alongside the text. We also angled our display boards to bring the casts closer to the front of the cases to improve their visibility to our visitors. This also helped us tackle the challenging low-angle lighting needed to illuminate the specimens.

Illuminating the start of early animal life is on display at the Sedgwick Museum until February 2020. The Museum will also be presenting an evening of talks about the Ediacaran fossils, including a talk by Emily, as part of the Cambridge Science Festival on 13 March, and will also be talking about her work at Super Science Saturday on 16 March in the Museum. Family workshops are planned for the Easter and Summer holidays – watch this space.