The Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA) houses outstanding collections from the Cambridgeshire region, but for much of this material little has been documented and photographed. What happens when we delve into this material, sometimes for the first time since it arrived in the museum, and how can we make it better known?

In 1923 Sir Cyril Fox published his PhD research The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region. This major work comprised of illustrations, photographs and detailed study of the collections housed at MAA. This got us thinking, what has happened in local archaeology since this publication? What developments have shaped our understanding? How have technologies changed the way we work? With the centenary anniversary of Cyril Fox’s study only a few years away it is the perfect opportunity to re-examine the archaeology of the Cambridge region. Much has changed in the past 100 years – not just through the increase in discoveries made but the interpretations of finds and our awareness of the historic landscape.

In October 2018 I began a project, Unpacking Cambridgeshire’s Past, to reassess local material in MAA’s archaeology collections. I chose first to focus my attention on our Iron Age metal work, a small discreet subsection of our material, to allow me to test out what kind of obstacles and questions I would face. The objective was to review the information in MAA’s database – to clean up records, photograph the objects and update missing contexts in order to better understand what lies within MAA’s stores.

I first had to think about what ‘the Cambridge region’ meant today. For Cyril Fox working on his thesis in the 1920s, the Cambridge region was anywhere he could cycle to and from in one day! This limited his survey but at the same time served to concentrate his studies to a controlled area. I chose to follow suit by first searching our database for Iron Age metal items from Cambridgeshire only. However I knew there were some key sites on the borders of Norfolk and Bedfordshire that required further study and so included these in my database search. With the kind help of MAA’s workshop manager many large, heavy boxes of objects were brought to the Keyser Workroom for me to work though.

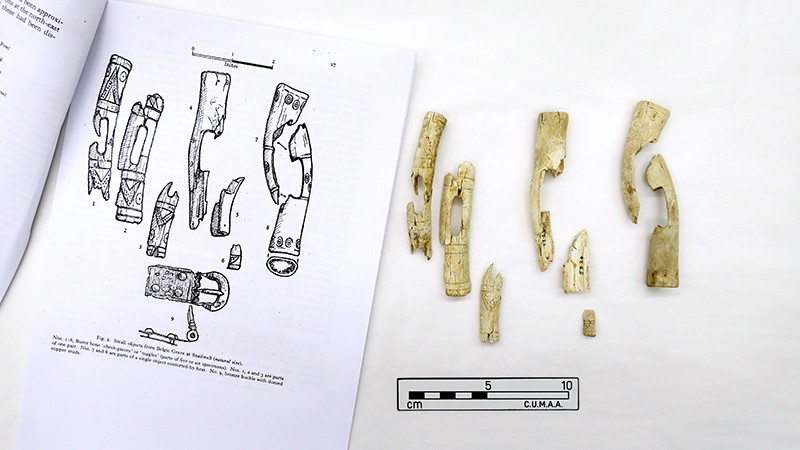

I began examining the objects and MAA’s database and found a great many inaccuracies within the data. Each object has to have its own unique identifying number – its accession number – in order to link any new information to the correct object. What I found was that some objects had been assigned incorrect accession numbers, some items had been boxed with other objects and so were classed as missing as they had not been in the correct place, and some objects were not accessioned at all. Publication references can give objects context whether providing an illustration of how the object was found in excavation or noting its association to other material or remains. Sometimes a database record would only have a plate number with no suggestion of the book or article this plate was in, and often no references were listed at all. And finally, many of our records did not have any photographs and so lacked a visual representation of the object.

To address these issues I first confirmed or reassigned each object with an accession number. Each object now has a unique identifier that allows for it to be searchable on MAA’s database. I found missing items by simply emptying complete boxes and systematically checking each object back in. I scoured a number of publications, such as the Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society (PCAS), and found references, figures and photographs of many of MAA’s objects. These improved object bibliographies provide extra information to their contexts. Last but not least I took a photograph of every object and uploaded these to the database. All this will allow for anyone whether a member of the public, independent researchers, museum and university staff and students better access to MAA’s collections.

Since Unpacking Cambridgeshire’s Past began I have worked through nearly 550 database records, cleaning and improving documentation and photographing these objects – but this is only the start. Over the next few years as we approach the centenary of Archaeology of the Cambridge Region I hope to target other collections from the local area from every time period. This will allow better understanding of our own collections with the aim of a major temporary exhibition to open in 2023 showcasing the past 100 years of archaeology in the region, and at MAA, and what we have learnt since Cyril Fox’s publication.

As a taster of this work, later this year, MAA will display material associated with the theme of feasting in the Iron Age in the Spotlight Gallery. This has been made possible by renewed understanding of our own objects and collections, with some of the material never being displayed before.

Unpacking Cambridgeshire’s Past has been generously supported by the Cambridge Humanities Research Grants scheme.

Feast! will open on 8 October 2019.

View MAA’s online database.