How do museums add to their collections? The answer varies, and it depends on the type of museum. Generally it’s through some combination of responding to offers of donations* or through projects to make carefully targeted acquisitions in an area where the collection might be lacking.

*As I type this I can hear the curators and collections teams shouting at their computers: “please tell everybody not to send us their things without speaking to us first!” Space is at a premium, and unfortunately museums can’t accept everything they’re offered.

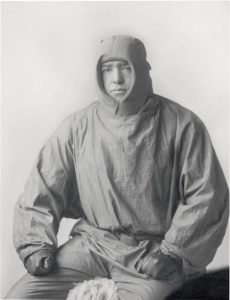

By Endurance We Conquer – The Shackleton Project

Some museums have dedicated budgets to buy objects and artworks, but for many museums donations are the principle means of growing their collections. From 2014-19, the Polar Museum and our colleagues in the Scott Polar Research Institute’s archive, library and picture library were fortunate enough to hold a National Lottery Heritage Fund grant which gave us a substantial budget especially for buying materials related to Sir Ernest Shackleton.

‘By Endurance We Conquer – The Shackleton Project’ presented a rare opportunity to actively look for material over the centenary of Shackleton’s most famous expedition, where he and his crew beat all the odds to survive after their ship, the Endurance, was crushed in the ice in Antarctica.

Over the course of the project, that’s exactly what we did. We approached individuals we knew who held materials related to Shackleton, worked with dealers and bid at auctions, and successfully enhanced our nationally significant collection of material. Our focus was on making acquisitions that would help researchers, rather than necessarily trying to buy the most desirable or collectable materials. That meant, for example, that where we already held a transcript of a diary, we didn’t necessarily seek to buy the original.

What was added to our collection?

One of the objects we acquired was a barometer, believed to have been used by Edgworth David during Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition. David reputedly used this barometer to help determine the altitude at the summit of Antarctica’s most active volcano, Mount Erebus, having led the first ascent.

What challenges did we face?

Despite the luxury of having a large budget available, the project wasn’t all plain sailing. Shackleton is a hero to many, and we weren’t the only ones trying to buy collections related to him. At auction we were frequently out bid. The timing of the project to coincide with the centenary meant that more material came to market, but also that more people were aware of Shackleton and wanted their own piece of history. Although we had a large budget we were, quite rightly, limited by ethical considerations. Before any potential large purchase we sought an external valuation which provided an upper limit. This is essential when spending public funds, but meant we were outpaced by private individuals with deep pockets.

Nevertheless, the project can be considered a success, particularly in collecting material that supports our research aims and enables us to tell stories about the less well-known expedition members.

‘We hold more of the documentary material than anybody else, and our collection is fantastic. I think that where we have been able to open it out a bit, is in terms of the so-called lesser lights of the expedition, of course everybody’s important on these expeditions, and I think that there we’ve actually done quite well.’ – Anonymous quote from an internal stakeholder

Find out more

Click to download the full evaluation report about the project, produced by independent evaluation consultant Catherine Mailhac.

You can learn more about our collections relating to Ernest Shackleton, and access online learning resources, audio descriptions and short films on our Shackleton Online web pages.