Various individuals influenced the Egyptian collections here at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA). There are some very unusual characters – like the banjo playing Lady Meux – and there are some more reserved antiquarians and entrepreneurial collectors. They all, however, contributed to what we now see in the museum in one way or another.

The Chemical Experimenter

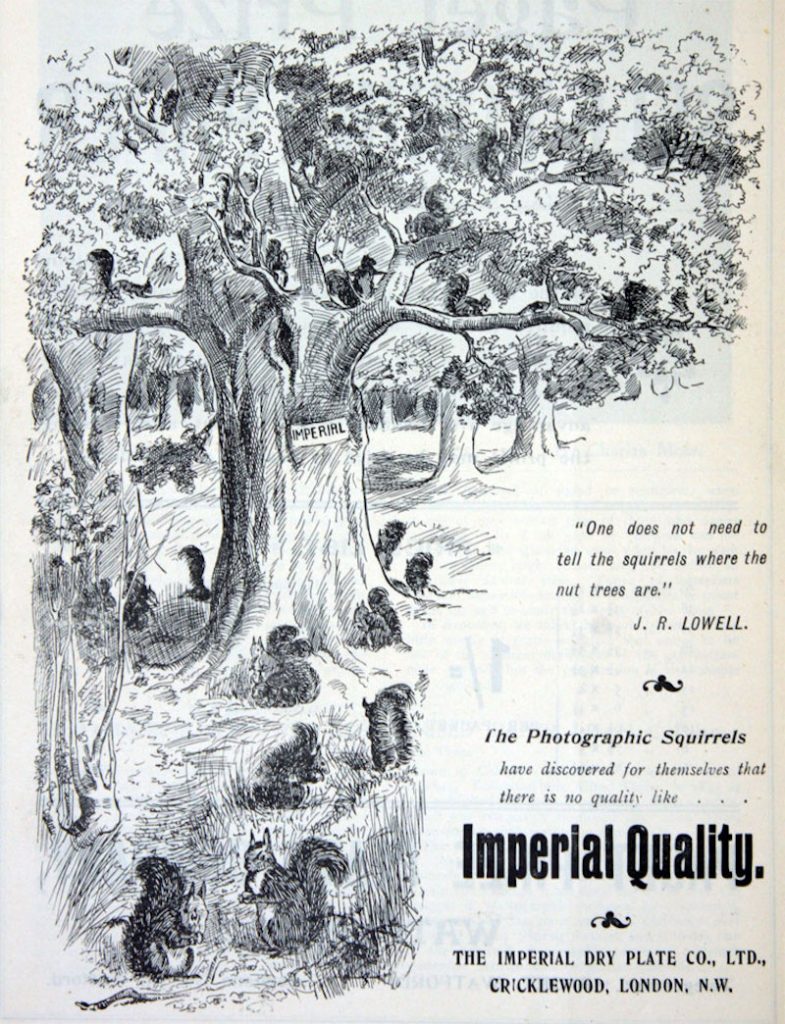

Joseph John Acworth was born in in Kent in 1853 and from childhood he was interested in the sciences. He focused his attentions on the actions of nitric acid on metals, first working in the Chemical Laboratories of the Royal College of Chemistry and going on to the London Institution. He was fascinated with photographic dry plate technology and for a short time worked at the Britannia Dry Plate Company at Ilford before heading to the University of Erlangen, Germany to complete his PhD.

He returned to England in 1890 and identifies himself in the 1891 census as being a Chemical Experimenter! This was evidently an excellent description of himself. Being a man of independent means allowed him to build a laboratory in Cricklewood. His work grew and in 1892 he established the Imperial Dry Plate Company. He was aided in his endeavours by his wife Marion Whiteford Acworth, an accomplished scientist in her own right – the first woman to receive the Associateship diploma from the Royal College of Science in physics in 1893.

Interests in Egypt

It seems that Joseph did not have an archaeological background but his interests in the ancient Egyptian civilisation grew later in life.

Suffering from asthma Joseph decided to sell the Imperial Dry Plate Company in 1917 to Ilford Limited, another large dry plate company. On his retirement he resided abroad for prolonged periods of time so as to improve his health, one country which both he and his wife fell in love with was Egypt.

Whilst he bought some objects during his time living in Egypt, it appears he was already intrigued with this county’s ancient history and its material culture. When in England he would attend auctions – some of which were the largest and most famous of their time such as that of Lady Meux in 1911 and Lord Amherst in 1921. Like many other private collectors of his time Joseph amassed a huge collection of largely small objects – mainly shabtis, scarabs, amulets, jewellery and other easily accessible items that would be suited to the upper middle-class gentleman and his home.

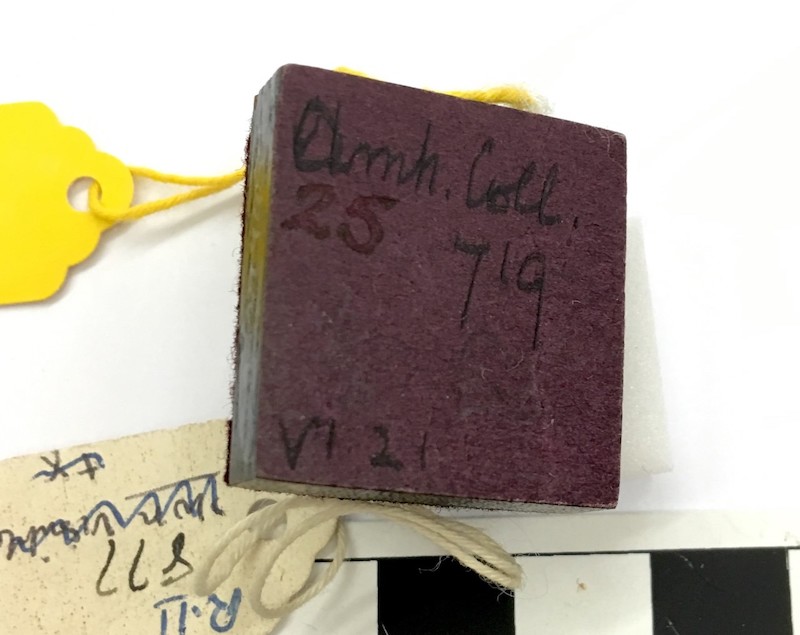

In most cases Joseph noted where he obtained each of his objects on the underside of the object’s mount. This has allowed us to build up a picture of where he was and when, and raises questions on the kind of social networks that arose amongst private collectors of the time. Would he know other buyers at these auction houses, the sellers themselves, would there be a healthy competition or rivalry for the different lots?

Collections on display

We don’t yet know if and how Joseph’s collections were on display at his home or in his offices. Whether they would have been a conversation starter for his visitors or if they were solely for his and his family’s own interest.

We do know that some of his collection was incorporated into the 1921 Summer exhibition Ancient Egyptian Art, curated by the committee of the Burlington Fine Arts Club in Mayfair. He is listed as a contributor amongst some of the most well-known collectors and Egyptologists of the time such as the Reverend William MacGregor and Howard Carter. This exhibition was created in collaboration with the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Society) and sought contributions from other institutions such as the University of Manchester and the British School of Archaeology in Egypt. This clearly indicates the importance assigned to Joseph’s collection and may hint at his social and intellectual position within the subject. In his Obituary, from the Photographic Journal in 1927, ‘W.B.F’ wrote that Joseph had become a well-known authority on Egyptian antiquities after his retirement from the dry plate business.

The Acworth Collection at MAA

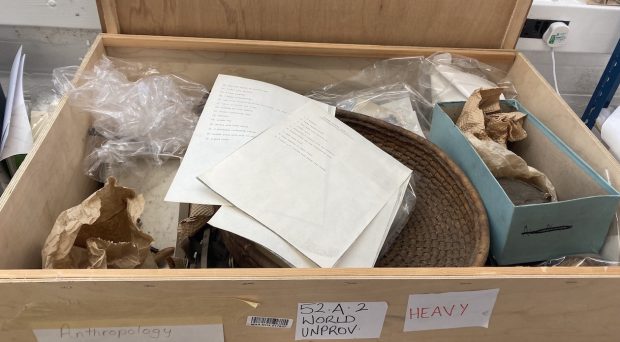

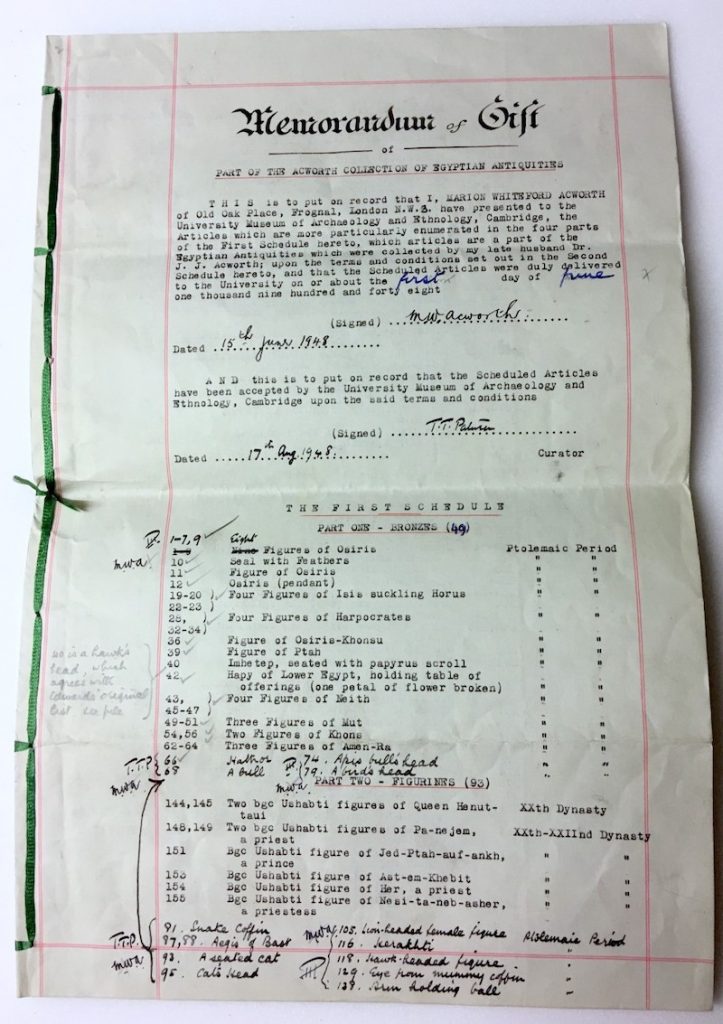

Joseph died in 1927 and left his collection to his wife, Marion. In 1939 Marion approached the British Museum and offered her husband’s extensive collection. The outbreak of war delayed the British Museum’s selection process but in 1946 they selected some 600 pieces that filled gaps in their existing collections. In 1948 the rest of the collection was offered to MAA – we do not yet know what kind of connection the Acworth’s had with Cambridge, or indeed if MAA was suggested to Marion as a repository for her collection after working with the British Museum. Around 1000 objects were given by Marion and contributed to MAA’s extensive collection of Egyptian antiquities. This gift included a huge number of scarabs and amulets, bronze figures, jewellery and the ivory inlay from a box belonging to Rameses IX.

Some of Joseph’s scarabs, amulets and shabtis can be currently seen on display in the intro case on the ground floor of MAA.

You can take a virtual look at MAA’s collections here