The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has a collection of around 1,500 Japanese prints. I investigated how we can ‘read’ these pictures to understand more about the cultures that produced them.

Japan had a flourishing print culture in the 18th and 19th century. Japanese prints became objects of fascination for Europeans in the 19th century, but the stories the pictures told were often not well understood by western enthusiasts.

Nevertheless, their remarkable visuality was inspiring to artists like Van Gogh, and charmed collectors like E. Evelyn Barron, who gifted his large collection to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1937.

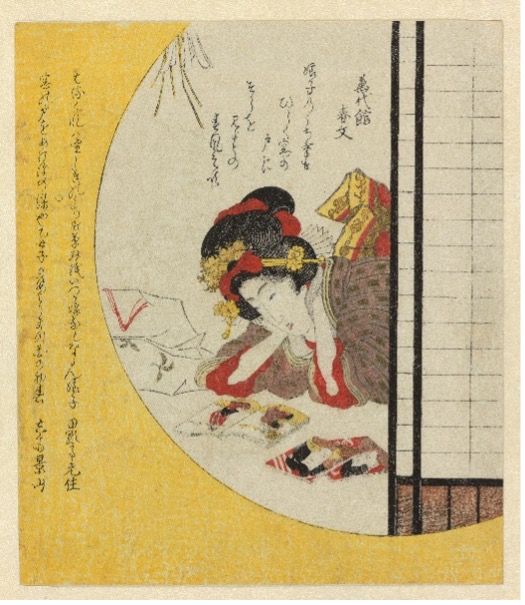

One of these prints shows a young woman framed by a vivid yellow ground: she has thrown off the wrapper from a set of books and is gazing at pictures of actors.

Japanese printed media could be relatively affordable, with a single sheet picture costing about as much as a bowl of noodles. This picture however is more of a luxury object. It’s a surimono, a lavish print using techniques including metallic pigments and blind embossing, showcasing the printmakers’ technical skills.

Reading Japanese Prints

Japanese prints, whether inexpensive or luxurious, often contained writing, whether poetry, titles or speech bubbles. The frequency of written elements reflects the high degree of literacy in Japan in this period.

Surimono like this were commissioned by poetry groups to celebrate the New Year, and carried poems produced by members. Here, one poem is above the girl’s head and two more are in the yellow area on the left.

Here the designer is HARUKAWA Goshichi (the family name is capitalised), and his design has generous negative space for the poetry group’s compositions. Both poems and pictures tend to reference the season for which they were produced. New Year in the old calendar was early spring, and here the poems take as their theme the wind of spring. Reading the poems then might draw our focus to the paper decoration dancing in the breeze above the young woman’s head.

The poems remind us that this is a season of budding growth, and soon trees and plants will start to burst into full flower. Alongside the poetry, the girl’s dreamy gaze on the handsome actors seems to hint at the burgeoning emotions of a girl blossoming into adulthood.

We understand more about the picture when we read both text and image together.

A glimpse into the Floating World

Japanese prints are sometimes called ukiyo-e, ‘pictures of the floating world’, a reference to the demimonde of the red-light districts, where pleasure-seeking provided an escape from real life for those men who could afford it.

For the majority of people, this was an impossibly expensive dream, and they relied on pictures of famed courtesans and celebrated actors to provide a glimpse into the glamorous but unreachable ‘floating world’.

Although we sometimes use ukiyo-e as a general term for Japanese prints of this period, not all prints are of courtesans and actors.

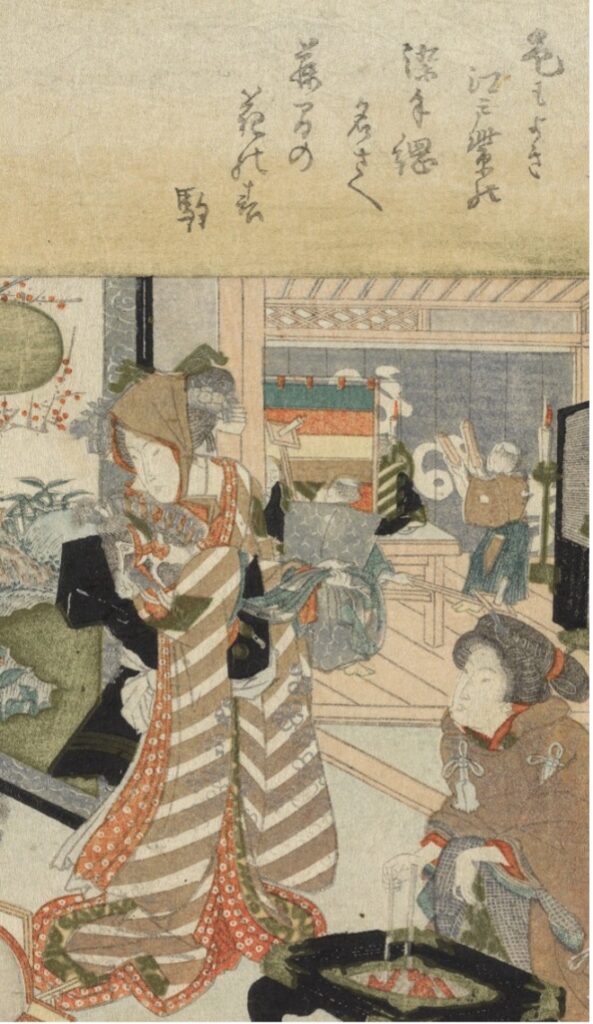

When I saw a surimono luxury New Year print described in the records as ‘fashionable ladies visiting an actor’s dressing room’, I was immediately intrigued. The idea of women visiting an actor in his dressing quarters sounds scandalous. Since actors participated in the sex trade, are the ladies his fans, or something else?

Looking at the print, we can see it depicts a backstage area. Through the doorway in the upper right there are stage curtains and musicians preparing for a performance, and the point-of-view is from within a dressing room furnished with mirrors, makeup, and lamps. There are two demure-looking young women in matching geometric long-sleeved furisode gowns (‘fluttering sleeves’ signifying youth) with two well-dressed older attendants, and seated at the back of the room is an important looking man, presumably the actor.

Why would wealthy young ladies want to be seen in public visiting an actor in his dressing room? Why are they tying their bonnet strings? Why is it they who are using the mirrors, not the ‘actor’? The apparent actor – who doesn’t look like an actor – is at the back, laughing jovially with an almost fatherly, encouraging air.

Interpreting prints

To try and understand what this picture shows, I looked at the three poems arranged across the top of the print. Here’s my translation of the poems, which use the 5-7-5-7-7 syllable count of Japanese waka poetry:

Iro mo yoki

Edo-murasaki no

some-tazuna

na sae Fujima no

haru no harukoma

The blush of Edo violet

Tints the reins,

The spring fillies are even named

After a glimpse of wisteria in spring

By Ryūotei Edo no Hananari

Kotemaki no

itoshi zakari no

harukoma wa

hikitodometaki

tsui no furisode

With their sweet curls

The spring foals are at a darling age

I would catch hold of a pair of sleeves

To stop them going further

By Hakuhatsu Sanzenji

Nobe mireba

mina ominaeshi

mutsuki sae

futatsu tsuretaru

uma no harukusa

I look out on the meadows

And see damsel-flowers everywhere

The first month even brings

A pair of fillies to the sweet grass

By Yomo no Utagaki Magao

This initially only made things more bewildering: all the poems use the word koma, an elegant term for a young horse. In poetry, this is a motif of late spring, whereas New Year was in early spring. Indeed the last poem seems to acknowledge that the season is too early for foals: ‘the first month even brings a pair of fillies to the sweet grass’.

At the same time, the poems drew my attention to the hobby horses in the dressing room – one tucked in the standing girl’s arm, and another on the floor beside the kneeling girl. Hobby horses were part of a New Year folk traditional where dancers with hobby horses went door to door; like the plum blossom on the folding screen at the back of the dressing room, hobby horses point visually to early spring.

The young foals in the poems may reference the hobby horses in the print, for this viewer at least, but the praise for the sweet youth and beauty of the foals is metaphor for the girls in the print.

It is the first poem however which really explains what is going on in the picture. Its mention of a ‘glimpse of wisteria’ (my translation for fuji-ma ‘wisteria’+‘space’) is another unexpected phrase, since wisteria is a late spring flower.

However, Fujima was a school of dance established by FUJIMA Kanbei in the early 1700s (the school still exists today and is currently led by FUJIMA Kanjūrō VIII), and the poem mentions the dance school with a play on words using the choreographer’s name.

The young women in the picture have been learning dance at the prestigious Fujima School, and are preparing for their New Year performance, which has been choreographed to use hobby horses in a nod to the seasonal folk tradition. It thus seems quite possible that the ‘actor’ seated at the back of the dressing room was Fujima himself. (Thank you to my colleague Joseph Bills for pointing me to a database of the surimono commissioned by the first poet, Ryūotei Edo no Hananari, the 11th daimyo of the Chōshu domain and poet.)

Reading the surimono raises all sorts of new questions – what did the other prints in the series depict? Was there a personal connection between Hananari and Fujima? If the man in the print is Fujima, which generation are we looking at? However one thing can be laid to rest. These are not fashionable ladies visiting an actor’s dressing room.

Prints as objects

Clearly, reading the text illuminates Japanese prints in a way that just looking at the pictorial content does not.

However, that is not to downplay the pictures themselves. Now that we have digital technologies, museum objects can be shared widely, including with readers of this blog, but we should not confuse looking at digital images with looking at the thing itself.

Surimono are an excellent case in point: as luxury private commissions, they were an opportunity for printmakers to showcase their mastery of complex (and expensive) techniques. Digitisation allows me to show you an image of a print, such as this beautiful surimono:

Looking at this image, you may not be particularly convinced when I say this is beautiful. In fact this is a quite spectacular object, and this video shows a little more of what we might miss from the still image.

There is gold metallic pigment, and the red and deep black areas are burnished to a glossy finish, while the vertical purplish column on the right has a velvety matte quality. The white shell below centre uses mica to give it a subtle sparkle, and there is three-dimensionality from liberal blind embossing, for example on the gold area and the plum blossom design at the right.

I hope this gives a sense of how extravagantly beautiful the work of Japanese printmakers was. It certainly shows why collectors like E. Evelyn Barron were so enchanted. Japanese prints use highly fugitive pigments and cannot be displayed often or for long periods of time, but visitors to the Fitzwillliam can request to view objects in person in the Graham Robertson study room. I would highly recommend doing so.

See new display, ‘Women in Japanese prints‘, at the Fitzwilliam Museum from 20 August to 17 November 2024, exploring how women were depicted in the late Edo period.