Ruth Clark reflects on a new partnership between the University of Cambridge Museums and the Addenbrooke’s Hospital Dialysis Unit.

Starting in May 2017, two days a month the University of Cambridge Museums (UCM) have been going to the Addenbrooke’s Hospital Dialysis Unit with curious, historic, fascinating and sometimes just beautiful things from their collections. Moving around the wards, from bedside to bedside, museum staff have been having conversations with people, inviting them to look, hold, discuss and explore the collection objects and the stories they contain.

Attending the Unit is to be part of a community, one that is rich in relationships, shared experience and mutual support. Being a valued, enriching part of local community life is pivotal for the UCM and as such – being a part of the life of the Dialysis Unit makes real sense! The Unit is undoubtedly greatly valued by those who use the service and the staff held in high regard, yet people receiving dialysis can also share common frustrations with the experience: going to a Unit for treatment is very tiring and dominates their lives (with three, four-hour sessions needed per week, plus travel time), and their time there can pass very slowly.

“Being listened to is the most important thing & the museum teams have been brilliant at that. It really doesn’t happen often in medical settings as there isn’t time.” – Unit Team Member

Claire Joyce, Renal Social Care Practitioner, on the Dialysis Unit:

When a person has been diagnosed with chronic kidney disease and reaches a stage when their kidneys can no longer function well enough to keep them healthy and alive, this is when treatment will be considered.

Dialysis is an artificial way of removing waste products and unwanted water from the blood. Dialysis can be carried out in a number of ways, therefore Haemodialysis, is one of the treatments that can be chosen. This is where blood is washed through a machine. Most people who choose this treatment will either come to a dialysis unit to have their treatment or after assessment be set up at home.

Cambridge Dialysis Centre is a new unit that was opened in December 2015. Prior to the new unit we were based at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in an old ward that had been set up “temporarily “as a dialysis unit. We were there for over 20 years.

Cambridge Dialysis Centre has thirty-six dialysis beds which treats over 150 patients, Monday to Saturday. Patients come to the centre for their treatment three times a week and up to four hours per session. We have three shifts per day am, pm and twilight. Patients also attend the unit for training so that they can carry out their dialysis at home as well as attending clinics.

The unit not only provides support to patients with their dialysis treatment but offers an individual and holistic approach of support, through the various members of staff working at the unit, such as nurse specialists, consultants, counsellors and social care practitioner, dieticians, as well as health care assistants, administration and volunteers.

What does the Curiosities programme aim to achieve?

- To contribute to people’s wellbeing, enhancing time in the Unit and fostering people’s curiosity and interest, enjoyment and happiness, and sense of interconnection.

- To extend the relevance of the UCM consortium’s collections through extending access; taking collections out of buildings and into people’s lives.

- Progression of the Unit’s role as community hub, supporting people’s health and wider wellbeing.

How does it work?

- Visits to the Unit are twice monthly (1.5 hours) on different days and at different times with the ambition of being available for all.

- Participants are people receiving dialysis, those accompanying them and unit staff.

- It is a UCM-wide initiative providing a rich diversity of collection items and areas of potential interest for participants.

- Engagement is at the bedside and the approach is informal and conversational; objects are placed on a trolley.

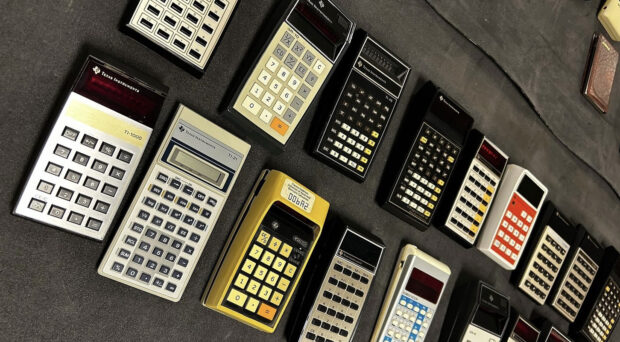

- Collection items are a mixture of ‘the real thing’ (where possible) & replicas (where not); predominantly they are from the learning teams’ resources.

- On average two museums visit the Unit to facilitate a session.

- Participants choose whether they would like to ‘have a conversation’ and select from the objects on ‘the trolley’ – or not!

- Conversations last an average of ten minutes with approximately twenty people taking part during each visit.

- Engagement is extended beyond the visit through museum programme literature, postcards / information materials & a regularly updated ‘object of the month’ display at the Unit.

“You could really look at stuff and find out about it. There was no rush and it gave us something new to do while we were here.” – Participant

Being a part of life at Addenbrooke’s isn’t new for the museums, with previous activity having taken place on the oncology ward. Beyond clinical settings, the museums have for many years now worked in partnership with service providers and local organisations supporting, amongst others, people with a dementia diagnosis and their caregivers, people experiencing mental ill-health, children with life-limiting conditions and their families, and older isolated adults.

The New Economic Foundations Five Ways to Wellbeing i.e. to learn, connect, be active, take notice and give provide a helpful frame to our understanding of why museums are so very effective in supporting ‘wellbeing’ and subsequently our health. During a museum visit or experience we can become immersed in finding out new things together, exchanging ideas, experiences and opinions whilst being in and exploring new, public orientated spaces and environments.

For the Curiosities programme, the headline outcomes that can be understood through the Five Ways to Wellbeing are: enjoyment or happiness through learning, personal connection and curiosity and taking notice through being immersed in the experience.

Evaluation is ongoing with the ambition of understanding impact and outcomes. The approach to evaluation has been threefold: plenary sessions with participants, post visit surveys by museums teams and focused debrief sessions with the Unit staff.

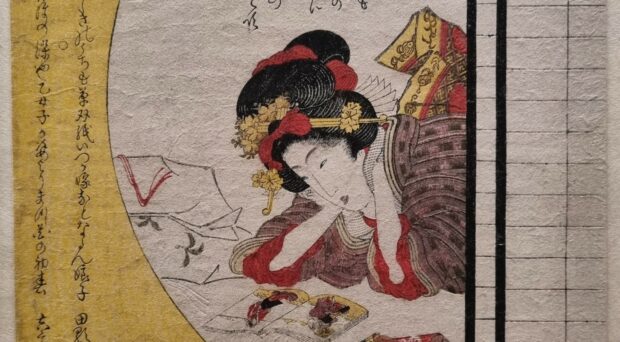

‘Interesting’ was the most frequent descriptor used by participants and Unit staff in response to the ‘conversations’ and people were frequently surprised by the feel of the objects when held. The stories behind objects and artworks were also key, with the facilitators personal take on these opening-up shared thinking about the related whys, hows and whats. Both are great examples of what is possible when working in a more intimate dynamic – be that for a limited period.

“We used to go around places looking at all the art … now we can’t, this is wonderful … it’s also been surprising what art you’ve brought. When you say Turner, well you expect seascapes – you showed us trees!” – Participant

‘Enjoyed’ was the second most frequently used word to describe the experience by participants and the Unit – the rating given to this by the museums was the joint highest. What appears to be effective is the combination of the artefact with the opportunity to have an enjoyable conversation. Understanding / defining this pivotal aspect of the practice will be a key objective as the work moves forward.

“We tell our daughter about the sessions, what we’ve seen, what we like, found out about, she likes art, we tell her about what surprised us, new things that we’ve learned – it’s a great shared thing.” – Participant

Having the space and opportunity to make personal connections, draw on individual knowledge and experiences, explore ideas and emotional responses are factors that we believe, when they come together, create ‘great conversations’. In a sense, these principles are very much about engagement and exchange rather than a more didactic, one-sided modality that museums can be perceived as being guilty of. The evaluation provides evidence that personal relevance and connection is abundant in the conversations that have been taking place – ideas of being seen, using and building on what is already known have been particularly strong.

“(It) involves ME as a patient with it instead of other things that you must put up with.” – Participant

“Good if you’ve got a bit of knowledge, know something about things, like the Shackleton story, you know bits of it and then ‘she’ tells you new stuff, stuff you didn’t know.” – Participant

What’s next?

In February 2018, the Unit and Museum teams will review the achievements to date and plan the next stages. It is likely that the structure will remain similar, however we will have the opportunity to use the evaluation and our experiences to date to refine and develop practice, especially around the ingredients of a ‘great conversation’.

One idea to help us reach more people in the Unit during visits, is, where there is capacity, to train and work with a wider team of staff and volunteers. Developing resources to support visits will be key to the success of this, whether they be replica objects or indeed originals that are suitable for handling.

In doing both these things the museums will not only be able to be an effective part of life at the Unit, but also be able to extend our work in the community, supporting people on a one to one basis, taking the museum ‘out of the building’ and into people’s lives, reaching specifically those who are unable to access these treasure troves of enjoyment, curiosity and learning.

A final note from Claire Joyce, Renal Social Care Practitioner

We have really enjoyed the whole experience of having ‘Curiosities at the Bedside’ come to the Cambridge Dialysis Unit and it really has exceeded our expectations. Patients are engaged and enthused about what they are shown and really look forward to speaking with the team about the curiosities they bring.

This project is a first in the history of the renal service at Addenbrooke’s and I do believe that there has not been anything like this in any other dialysis unit in the country. I would love to see this develop into reaching more patients at the unit and perhaps holding regular activity sessions through the year for patients who are not regulars – for example, an biannual organised talk/discussion held in the reception area.

I would also like to get to the point where we can start to think about offering this service to our other renal units which are based at Hinchingbrooke Hospital, West Suffolk Hospital and QE2 in Kings Lynn.

Finally, I would like to be able to showcase the excellent and innovative work that has been done here at Cambridge Dialysis Unit at a national level, by submitting an abstract to the British Renal Society and designing a poster for their annual conference.

Curiosities at the Bedside has been facilitated to date by the following museums: Museum of Classical Archaeology, Fitzwilliam Museum, Polar Museum, Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, Museum of Zoology and Kettle’s Yard.