Entirely too easily, I sit in a culture bubble wherein the atrocities of Empire (and their continuing reverberations) are widely acknowledged. So I was immensely upset to read that 59% of people in Britain are still proud of the British Empire.

By extension, I am sad that these proud people, if or when they visit a museum, might wander throughout its galleries feeling proud of British museum collections as symbols of gains made during Empire – potentially not questioning the routes by which these objects may have made their way into a collection.

Hopefully this is not the take-home message for 59% of visitors to The Past is Now, a temporary exhibition on until the 24th June 2018 (go if you can!!) at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG). This is an exhibition with a clear voice, decolonising the museum’s collection and speaking on behalf of historical and contemporary people from ex-colonised states who have been subject to such an insensitive national opinion.

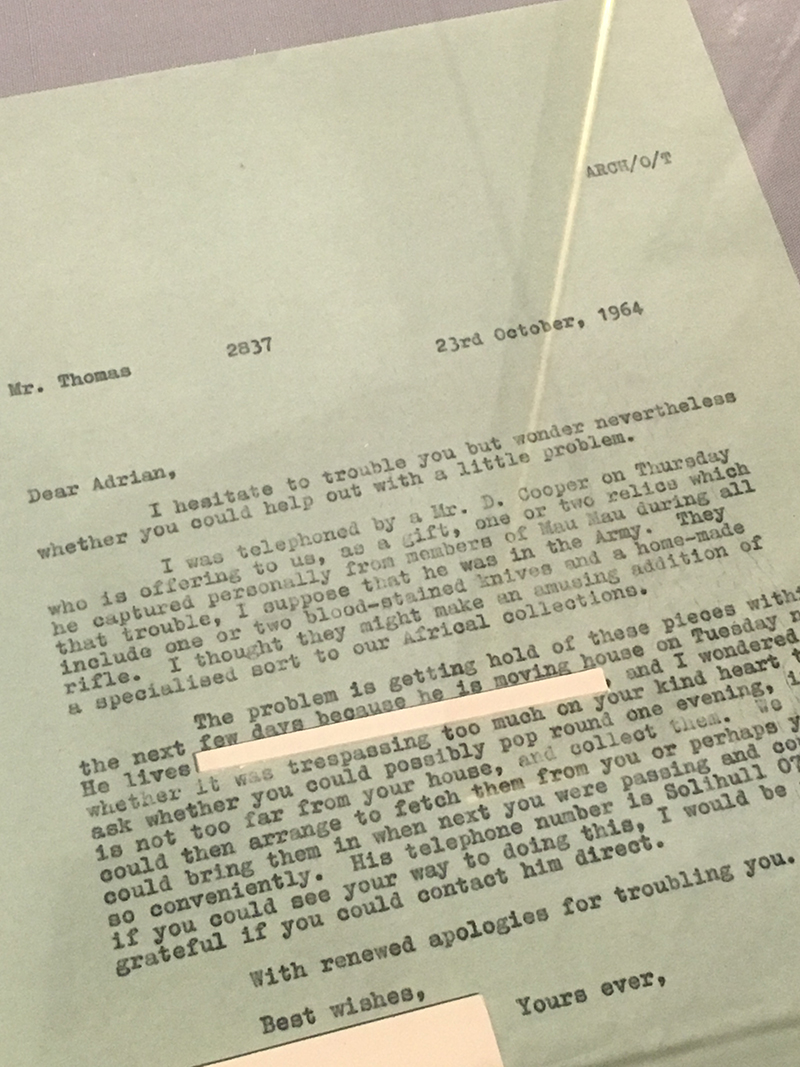

The Past is Now was co-curated by six creatives and activists. The exhibition demonstrates the continued impact of Birmingham’s involvement with the British Empire by pointing to some of the darker components of BMAG’s collection, thus narrating more holistic histories. The exhibition uses artworks to demonstrate continued responses to the realities of life for diasporic communities in the UK, and asks questions of visitors: ‘What did we learn about Empire at school?’ and ‘How is the British Empire relevant in 2018?’ (Although I can’t resist saying that I actually wish the exhibition was a bit bigger, more prominent, and that it was also clear what the legacy of their decolonising narrative will be.)

I was fortunate enough to go to BMAG with the University of Cambridge Museums’ Change Makers Action Group, and was especially thinking about how we might bring the benefits of co-curation and an open honesty to the University of Cambridge Museums (UCM) – even if the result contradicts our museums’ dominant narrative. I was also considering the incredible difficulties that would be inherent in this somewhat uncharted territory – especially at the University of Cambridge, frequently contentious for its collecting habits and utter lack of diversity. Co-curation ensures that systemic narratives are challenged by the appropriate people, whilst also offering opportunities to a range of more diverse storytellers, creatives and historians and thus ensures we are speaking justly to all types of people, including those that need fair representation the most. This is something that The Past is Now undoubtedly achieves, made even more significant by its location within Birmingham, a city where 46.9% of the population are from black or minority ethnic groups.

And yet, I was struck by concerns I’d heard at the Museums Association Conference and seminar, ‘All Inclusive: Championing Diversity in Museums’, that the process of co-curation was difficult. Co-curator Sumaya Kassim writes more about the project’s incredible successes alongside the struggles in great depth. Of course, co-curators must be involved because they have a valuable perspective to share, and one that will challenge the museum’s dominant narrative. Yet for these individuals the history is significant and personal. Therefore, situating such an exhibit within a museum – a space which the public generally assume to speak the truth, but where this history has previously been systematically mistold – means that the process of restructuring this narrative must be challenging on a personal as well as a practical level. Hence, museums must be incredibly sensitive in regards to this personal element. The risk of accidentally creating some sort of neo-colonialist museum microcosm is very present and must be mitigated – although co-curators must struggle to decolonise, this struggle must be with the history and collection rather than with the museum’s contemporary structure. So what is the solution for this? Is it as simple as managing everyone’s expectations? For, once this complicated – but incredibly worthy – process is finessed, museums can democratise opportunities to share histories and create powerful and socially just spaces from which everyone can benefit.

Rosanna is a co-chair of the Change Makers Action Group, which aims to drive a conversation about representation within the UCM’s collections and audiences.