Antony Gormley is one of 7 Royal Academicians, who have connections with Cambridge, taking part in RA250 at the Fitz.

We asked each to pick a work in our collection that has inspired them and tell us why.

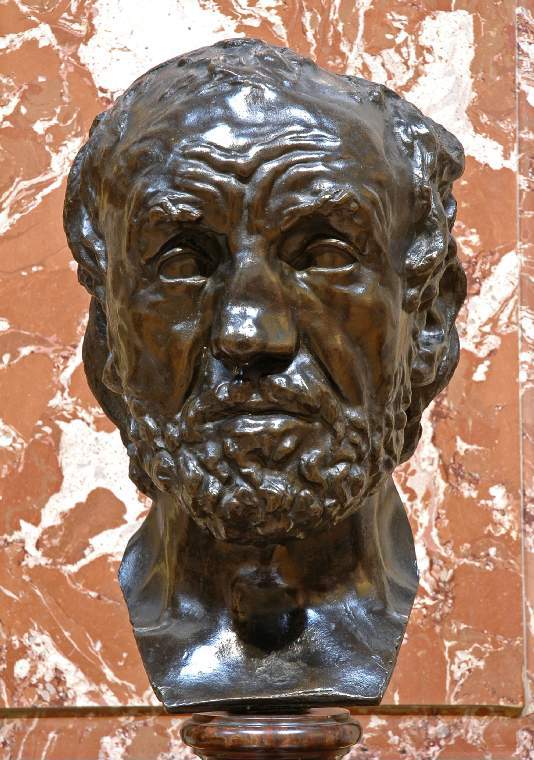

Antony chose Man with a broken nose, by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), on display in Gallery 5:

Here, Gormley explains why he chose this work:

“I remember it from my very first visit to the museum. It stands out as an awkward thing amongst the Bukhara rugs, hyacinths and the smell of furniture polish that grace the Fitzwilliam. It’s almost like this thing has been being dug up from the ground, something from any time in human history. Once you see this work, life-size and lifelike, it’s difficult to forget it. It seems classical but also very modern. It could be the head of an ancient (like the Arundel Head in the British Museum) but it’s also the portrait of modern man.

Rodin is perhaps the master of metonymy: this mask allows the face, visage, appearance to stand for a whole life. Time and experience sculpted this face before Rodin modelled it. There is something of Dickens and of Zola here. Idealisation and the heroic trope have given way to an interest in the street and a more generous idea of the value of human experience. Here is a man seen as a mask. Part of the poignancy of this work is not just that the back of the head fell off in the frost of the young Rodin’s studio but that this loss reveals the sculpture as a front, a cover, but a cover that reveals the truth about human experience. Rodin allows us to peer into the space behind the face, acknowledging that a hollow bronze is another form of illusion. Form becomes an empty vessel, inviting the projection of our empathy.

North Meadow at Trinity College

Photo: Rachel Sinfield

What is the feeling we receive or project? This man’s features: blank eyes, furrowed brows, broken nose, closed mouth offer us a potent expression of uncertainty. In spite of a life that has written its hard story across his features, this noble man is still lost, lost for words, for a place, lost for understanding.

This mask that seems to face the human predicament may well be the opening to an existential purpose for sculpture. A sculptural tradition that was designed to promote the ideal, the mythic, the heroic and the sexual now becomes engaged with questioning the nature of reality. The door is left open for Giacometti, Beckett and Artaud to deal with the human condition without the props of narrative, mythology, idealisation, or the norms of portraiture with their attendant flattery.

Rodin cannot be copied but the bodily, psychological and philosophical implications of his work are a continuing point of inspiration that asks how the body can be reanimated in the art of our time.”

Cast iron

196 x 48 x 35 cm

Installation image, Jesus College, Cambridge, U.K.

© the artist

SUBJECT at Kettle’s Yard

Why not combine a visit to see this Rodin sculpture at the Fitz with a visit to Kettle’s Yard to see the exhibition SUBJECT, which contains five of Gormley’s works, open until 27 August 2018.

Subject, 2018 at Kettle’s Yard

10 mm mild steel bar

185 x 52.3 x 40 cm

Photo: Rachel Sinfield

For SUBJECT, the artist has activated and disrupted the gallery’s new spaces. Insisting that the body is the mind’s first dwelling, Gormley has always wanted his work to interact with architecture and the earth.

The five sculptures in the exhibition interrogate the body in space and the body as space. The works use solid mass and open net structures to invite and imply our presence. All of these sculptures use front/back, left/right and up/down physical co-ordinates positioned at 90 degrees to one another to articulate both architectural space and the space of the body.

The ‘subject’ of this exhibition is as much our own bodies, their relationship to the sculptures in the gallery and to the architecture of the spaces, as the works themselves. SUBJECT might also carry us beyond these physical encounters, to consider an internalised, limitless space of the mind.

Cast iron

179 x 34.5 x 44 cm

Installation image, Sidgwick Site, Cambridge, U.K.

Photograph by Lloyd Mann

© the artist

Cast iron

195 x 57 x 42 cm

Edition 3 of 3

Installation image, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, U.K.

Photograph by Marcus J Leith

© the artist