The Green Museums project explores environmental themes across the University of Cambridge Museums (UCM). Our objects hide a history of how we have understood the environment and the problems it now faces, deep in their archives and in the objects in plain sight.

In this first instalment in the Green Museums blog series, Rosie Amos explores Earth Stories. Mythologies, fairy tales, fables, often have rather gruesome content, but what they also have in common is a means to pass down stories of morality in our actions to others and our treatment of the Earth.

Once upon a time…

…there was a Greek Titan who decided to embark on a craft project and made mankind out of earth and water (no sticky-back plastic needed). As the final touch for his creation he decided to give them a present, fire. Not a bad present, as according to the mythology, this is what allowed human civilisation to develop and eventually humans could make their own craft projects! Unfortunately our Greek Titan had stolen the fire from the gods and his dad decided the only fit punishment was to be attached to a rock and have his liver eaten by an eagle every day (it regrew at night).

This is the story of Prometheus, who has become associated with the striving of the human race for greatness, but also the unintended consequences of ambition. Mythologies, fairy tales, fables, often have rather gruesome content, but what they also have in common is a means to pass down stories of morality in our actions to others and the world around us. Nature is part of the environment we can all understand. The way in which society’s relationship with nature has changed over time is represented in these stories passed down through the generations. These can be seen most prominently in the creation myths of ancient cultures.

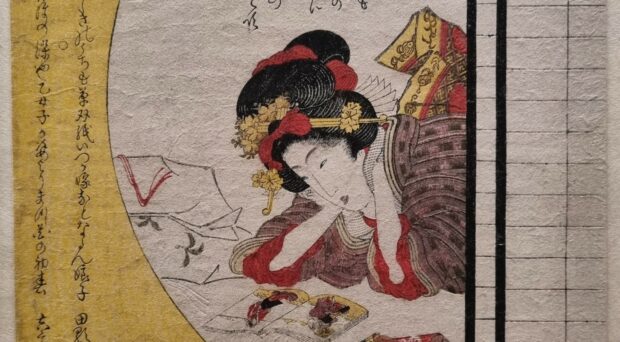

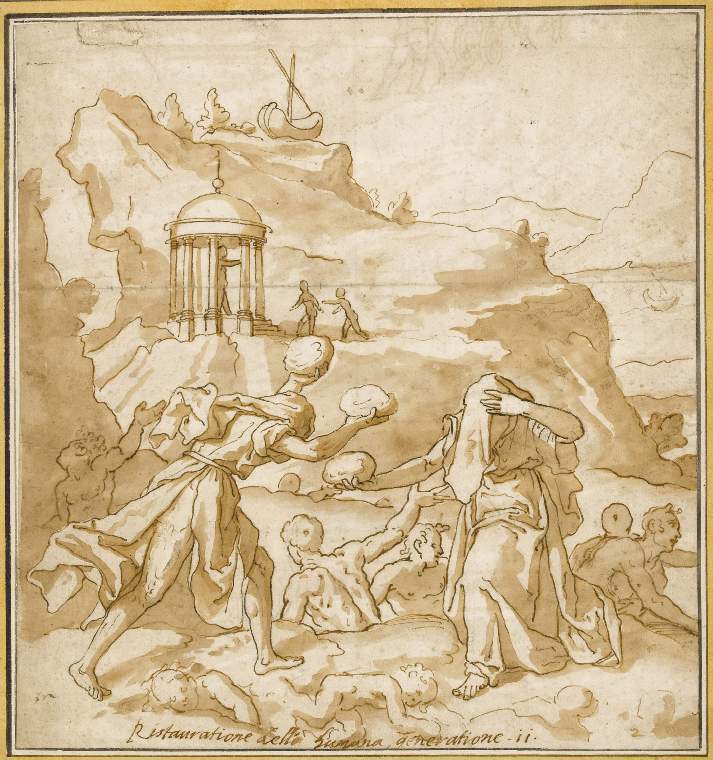

Maker/s: BASSETTI, Marcantonio, attributed to (Verona 1586-1630)

Technique Description: recto: pen and brown ink, brown wash

Dimensions: height: 289 mm, width: 270 mm. Fitzwilliam Museum

There are stories in many cultures of a Great Flood which is caused by human over-ambition and their destruction of nature; myths shown as a warning to those who do not respect the Earth. In the Greek legend of Deucalion (Prometheus’ son by the way), the god Zeus, maddened by the disrespect of men for the world decided that they must be punished by flood. Under Prometheus’ suggestion, Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha escape and float in a chest for nine days and nights and when the rain stopped, Deucalion sacrificed to Zeus to bring new people to the world to start again.

But these stories go back to even the ancient Egyptians. When you wander through the maze of galleries of the Fitzwilliam Museum and you find yourself in the Ancient Egyptian gallery, walk past the mysterious text covered slabs, shimmy past the eye-drawing tombs and on the top shelf in a darkened room, you will find a statue of Shu. It is only about 10cm tall and you might just miss it, but hidden in that little statue is a story of creation.

Creation stories are formed to try to explain the world we see around us using our observations of nature. The river Nile was such a prominent part of everyday life for the Egyptians, it follows that their creation story begins with water, or ‘Nu’. Out of the turbulent water came land. Shu was one of the first to be created by the self-created god Atum who created him from his own spit. He was the husband and brother of Tefnut (moisture), and father of Nut (the sky) and Geb (the earth). It was thought that his children were obsessed with each other, and were permanently locked in embrace. Shu intervened and held Nut (the sky) above him separating her from his son Geb (the earth). And so our little statue, Shu created the atmosphere which allowed life to exist.

These myths hold meaning even today. It is very fitting that we explore Prometheus here as it is 200 years since the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, also known as ‘The Modern Prometheus’, a tale of a man who went against the laws of nature and had to deal with the consequences.

If this has just whetted your appetite, you can find out more about Ancient Greece at the Museum of Classical Archaeology and Ancient Greece and Ancient Egypt at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

—

The featured image on this post shows a globe in the collection of the Whipple Museum of the History of Science.