Working in Collections Care at the Fitzwilliam Museum, the thought of people handling the collections can sometimes seem counter-intuitive.

Nevertheless, I attended a workshop on tactile access to collections ran by Touring Exhibitions Company (TEG) at thinktank in Birmingham. I found it invaluable for the information and tools it provided.

Why do some museums ask visitors not to touch the collections on display?

Collections care primarily focuses on the preservation of the collections. This is done by putting procedures in place to prevent damage and slow down the rate of deterioration of materials. One of the common ways that can cause damage to collections is through people (staff and visitors).

What kind of damage can occur?

Sometimes museum collections can appear more robust than reality. Here are some of the ways that collections can be affected by handling and touching:

- Poor handling can result in breakages where there may have been pre-existing weaknesses, e.g. old repairs or inherently small joints (which is why you never see a conservator carry a teapot by the handle!).

- The effect of moving and handling collections can be cumulative. For example, joints in a piece of furniture can become weaker each time it is moved.

- Pieces can easily get scratched, knocked, damaged whenever they are handled or moved. Museums have guidelines and procedures in place to minimise the risk whenever staff move collections inside the building and if something gets sent out on loan.

- The natural oils and excretions from our skin can cause damage. If you place your hand on a copper saucepan it won’t be long before you can see the damage!

- Abrasion of surfaces on a lot of materials won’t always show up straight away but after numerous touches it will become apparent. This kind of effect is often seen on old stone steps where the centre of the step has been partially worn away.

Despite all of the above, collections do need to be handled, whether for practical reasons (moving them around the museum) or for learning. For example, archive and libraries contain functional collections and to access the information they need to be handled. To find out more about how the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Manuscripts and Printed Books conservators deal with this particular challenge, you can read this blog.

Why handle collections?

The workshop had practical and theoretical activities to get participants thinking about the benefits of handling and how museums can deliver tactile access to collections safely.

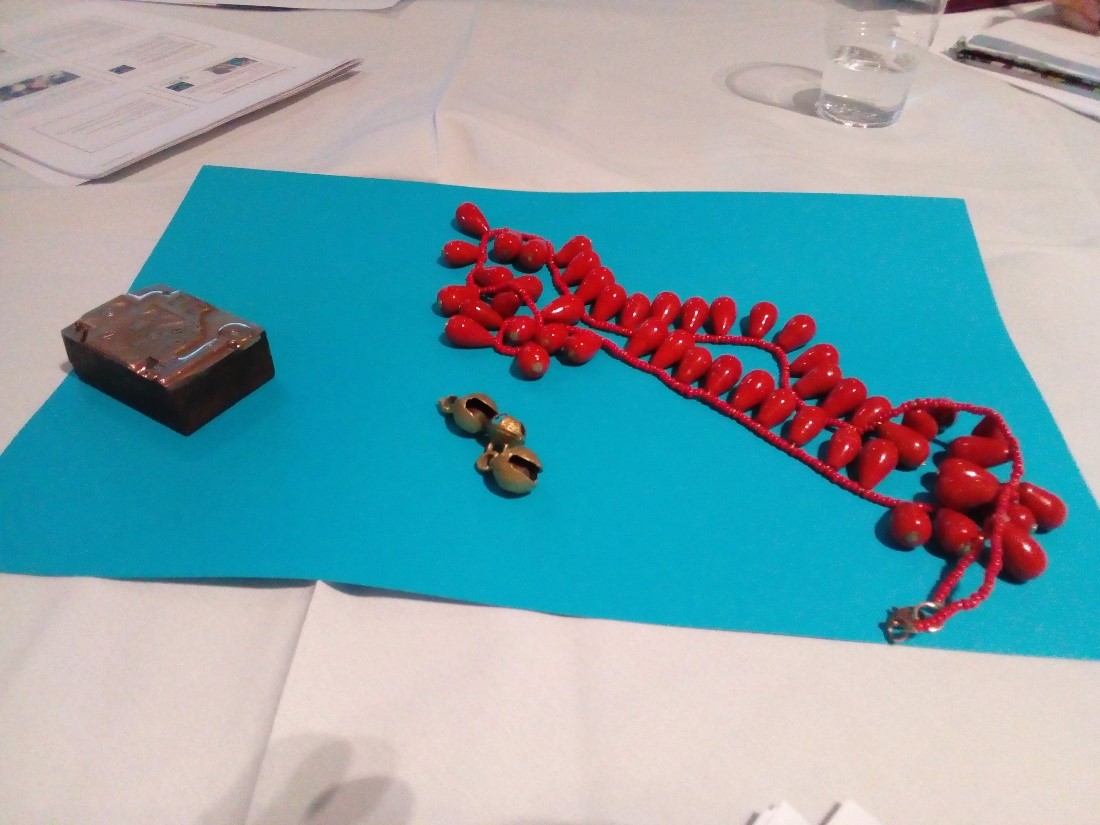

Often museums have handling collections. Sometimes these are made up of accessioned pieces (i.e. part of the collection) or they may be bought or donated items that relate to the collections.

Handling can give more information but can also raise questions – you cannot always discern the whole story by just looking nor just touching.

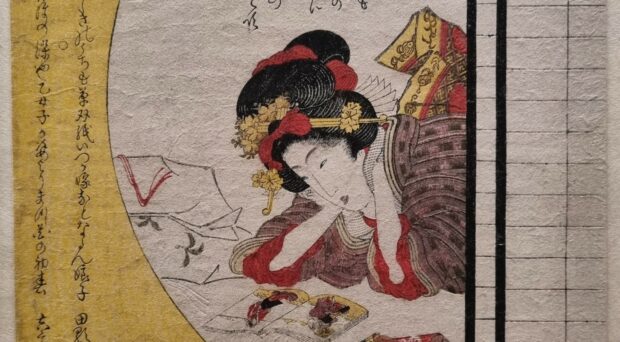

We were presented with a selection of objects and asked what we can observe from only looking. Colour is fairly straightforward, but what about materials? Weight? Function? Sound? Story?

This was a great exercise (and one I would encourage museum staff and volunteers to try!) to understand what you would be adding to the visitor experience by enabling handling or touching.

How can museums set up a tactile access programme successfully?

We were provided the tools to enable museums to set up or develop an existing handling programme safely.

Policy and procedures can outline standards and requirements for the successful management of a tactile experience programme. They can define the museum’s aims, the method for selecting objects from the collections and help identify the risks.

To enable a tactile experience, museums have several challenges including potential damage to collections and people, security, management and staffing, storage and transport (where applicable) and insurance. Therefore, risk assessments are key to a safe handling activity. From there, mitigations can be put in place to keep collections and people safe. This could be that staff or volunteers must be present or gloves must be worn. Equally though, it may be decided that the object is not suitable for handling at all.

The most powerful message I received from the course questioned how museums typically ‘think’. Often, museums have the policy that everything should not be touched and any handling should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Scary as it may sound to the museum professional, it is possible to switch the mindset of the museum – assume everything can be handled unless deemed too vulnerable or risky. However, policies, procedures and resources need to be in place in order to do this successfully.

Attending a course or conference is always a good excuse to have a nosy at what other museums are doing:

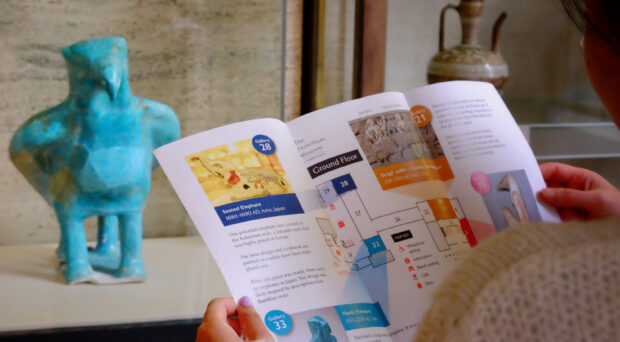

The Fitzwilliam Museum holds touch tours as way to make the collections accessible. The objects available for touching are a combination of replicas, non-collection items and collections items.