A museum full of rocks and fossils may not be the first place you think of to promote artist development, but our collections here at the Sedgwick Museum are doing just that.

In the autumn of 2018, Arts University Bournemouth student and model-maker Emily Manning approached the Sedgwick Museum. The museum was a childhood favourite of hers and she wanted to know if we would like to collaborate with her on a module of her University course.

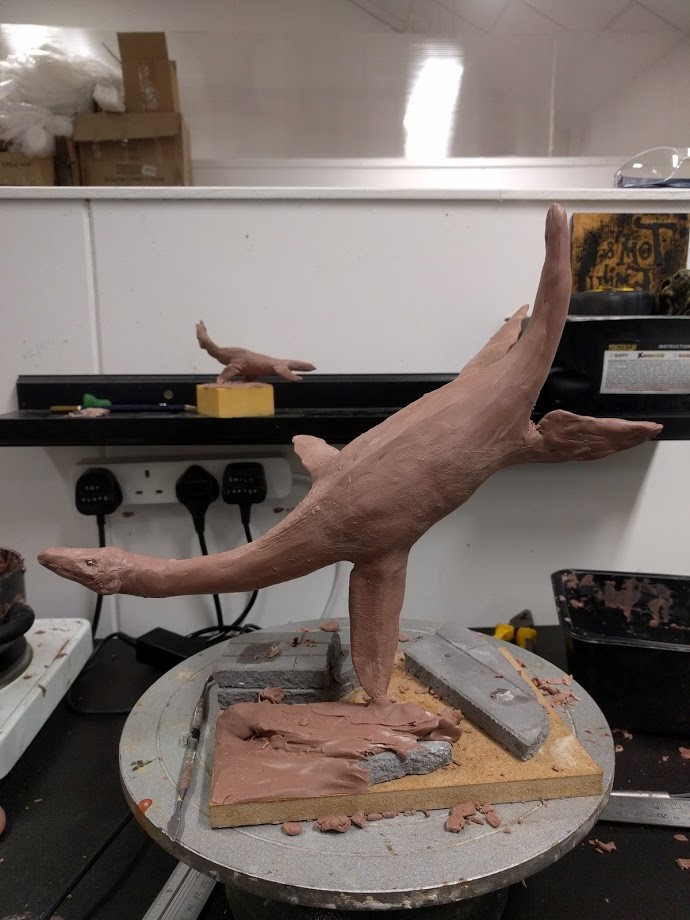

Exhibitions Coordinator at the Sedgwick, Rob Theodore, asked Emily to introduce herself and her studies, and to share her experience working with the museum on her latest model, the Jurassic plesiosaur Cryptoclidus eurymerus.

About Me

I am one-half of the model making company Creature Hut. I work as a freelance model maker and sculptor, with a dash of toy designer thrown in. My passion is for both sculpting creatures and for fabricating creatures of my own design. Alongside making physical models, props, and conceptual designs, I enjoy holding sculpting classes and demonstrations at our studio based in the south of England.

About the course

I am about to graduate from Arts University Bournemouth. I have been enrolled on their model-making course, which is really the only one like it in the UK. It is a very enriching environment, with access to high-end equipment and with students often collaborating on rewarding long-term projects. On this course there is not a project you can’t approach, resulting in a fantastic variety of work produced by students. We explore stop-motion puppets, animatronics, character design, and hard edge model making.

How did the project happen?

During my time at the University, I was able to produce this sculpture for the Sedgwick Museum, a much-loved museum from my childhood. I was interested in broadening my palaeoart portfolio, and it was a great time to seek out a new challenge based around reconstruction. Having already produced a sculpture of the Chinese feathered dinosaur Epidexipteryx for my previous module, and written about the evolution of palaeoart in my studies, it all fell into place to carry on expanding my portfolio. Having worked on projects in the past for other museums, it was a pleasure to once more be working on a piece that is not only educational for myself, but for the public as well.

Model making process and challenges

The build process for the Cryptoclidus was rewarding but hard work. There was a lot of design and studying before I could really get my teeth into the sculpture. The challenge lies with the fact there are no true and singular correct references for this animal, as it is now extinct! To combat this issue, I made certain to have an open dialogue with the staff at the Sedgwick Museum. This way I was able to get constant updates, opinions and relevant reference material straight from a very reliable source. As I was acting as the primary source of the physical model during this reconstruction, all the reference material was fed to me. I then had to translate it into something with a 3D presence.

Another method to make sure the anatomy of the animal made sense was to turn towards the concept of convergent evolution, when animals which are not closely related develop similar features because they are living in similar environment. I looked at the curves and movements of seals, and the head shape and eye placement of an anaconda. By studying living animals, it gave me an idea of how this animal would be move, and help deliver a sense of presence in the sculpture. During this time, I was playing with clay shapes, small clay maquettes and roughing out possible poses.

The physical sculpt was made from an oil-based clay called monster clay. It is a popular and user-friendly clay, which can be melted down and takes detail well at this size. I built a basic armature due to the centre of gravity in the sculpture, but most of the time this clay is self-supporting. Once the main shape and muscles were laid down, I could approach refining and smoothing out the sculpture. I inserted small ball bearings for eyes, and purposefully left the teeth out of the sculpture, as they would not survive the moulding process. I used a combination of special wrinkle tools to capture the skin texture of the animal, ensuring to leave natural feeling scars or skin imperfections for a more realistic look.

The clay sculpt was moulded with silicone and a plaster jacket was made, then it was cast in resin. Once I had the complete sculpture, it was time to assemble the head, which was produced in the same way. The sculpture was prepared for painting with acrylic paints, which used a combination of airbrush and hand painting techniques. The final step was to create the animal’s characteristic teeth. These were made from shaved down sewing needle tips, and individually insert them into the sculpture with a pin vice.

What was the most challenging part of the process?

Definitely ensuring the animal was anatomically accurate, whilst making sure its presence was visually interesting. I wanted to capture a dynamic pose and make its paintwork simple and natural, without looking washed out. It had an additional paint-job after its first completion date to help break up its silhouette and add a more mottled skin tone.

How did working with the museum help your development as an artist?

I learnt a great deal about reconstruction, far more than I did with my previous sculpture of Epidexipteryx, when I was working by myself. I met some very valuable contacts and was exposed to some fantastic palaeoartists, whose work is of great inspiration now. It was key to gain a deeper understanding on how to execute a good anatomical sculpt so I can launch myself into the next one with more knowledge and confidence.

You can see more of Emily’s work on her website, and on social media:

Twitter: @hiddenbeasts

Instagram: @creature.creature

Facebook: CreatureHut

We at the Sedgwick are always interested in exploring how we can work with artists and modelmakers to interpret our fossils. Get in touch with Rob Theodore directly on rjt60@cam.ac.uk.