Are there fakes scientific instruments hiding in our collections, and if so, how do we identify them?

Dr Joshua Nall, Curator of Modern Sciences at the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, introduces a research collaboration between the Whipple Museum and James Hyslop, Head of Department, Science & Natural History, Christie’s, London. The Whipple team included Nall, Professor Liba Taub and Dr Boris Jardine.

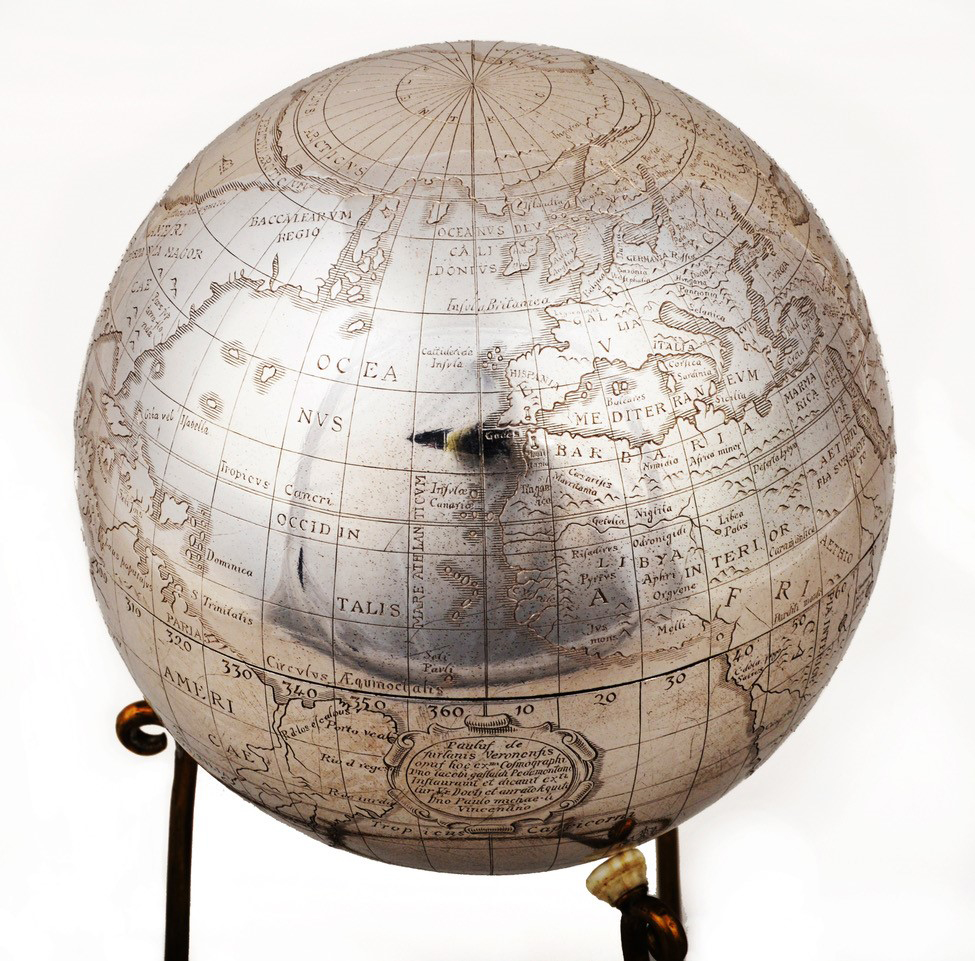

Since its foundation in 1951 the Whipple Museum has pioneered research into fake scientific instruments. The Museum’s second curator, Derek de Solla Price, effectively established this research area when, in 1956, he announced his discovery of the now notorious ‘Mensing fakes’. Working out from five fake instruments identified in the Whipple, Price unearthed a large haul of deliberately forged instruments in collections across Europe and North America, all traceable to a single source: the Amsterdam dealership Frederik Muller & Co., under the direction of Anton Mensing (1866–1936).

Since Price’s pioneering work the Mensing name has loomed large over scientific instrument collections, with dealers and curators particularly attuned to the problem of identifying suspect objects with an Amsterdam connection. This research project, established in 2014 as a collaboration between an instrument historian, a Whipple Museum curator, and a leading specialist in the instrument trade, seeks to further Price’s project by spreading the net wider than Mensing. By looking again critically at a range of instruments with provenances beyond Frederik Muller & Co., we argue that the question of fake scientific instruments has by no means been solved. The market for antique scientific instruments was fairly new and quite volatile in the first half of the twentieth century, and our analysis suggests that several dealers can plausibly be linked to the sale of forgeries, perhaps unwittingly, perhaps not.

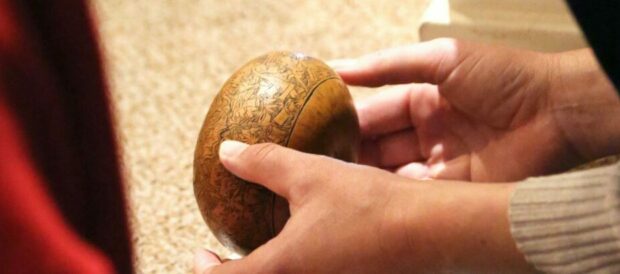

Our methodology includes both traditional techniques of curatorial analysis – exploring provenance; cross-comparison with other collections; scrutiny of engraving accuracy, palaeographic style, size, and quality of craftsmanship – and metallographic analysis conducted using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis.

Initial results have recently been published in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society, and include the identification of several new forgeries in the Whipple Museum’s collection, thereby further enhancing our understanding of our holdings and the historical context of many objects in the collection. At the same time, the antique trade’s ability to identify suspect object and expose forgeries before they come to market has been further strengthened by the involvement in the project of James Hyslop, a world-leading expert in the appraisal of antique scientific instruments.

This project has built upon many years of research into the manufacture, sale, and circulation of fake antiques. We have provided new insights into the early trade in collectable scientific instruments, including identifying at least one heretofore unexamined dealership with intriguing connections to more suspect aspects of the trade. This provides curators and collectors with one more strand of evidence for use in assessing the authenticity of objects in collections and those circulating on the open market.

How was the project supported?

The staff time of the three principle investigators was covered by their employers. The project has benefited from a great deal of pro bono work by researcher on early mathematical instruments Dr John Davis. Dr Davis conducted XRF analysis of a wide range of objects in the Whipple Museum’s collection, work that has been crucial for the project.

What next?

The project is ongoing, and we plan to develop a more systematic dataset of historic alloy compositions for use in dating and authentication scientific instruments. This will then be married to extensive existing data relating to instrument-makers and global collections of historic scientific instruments, with the ultimate aim being a web portal with a searchable database and related digital humanities resources.

Find out more

Preliminary results have been published in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society (Boris Jardine, Joshua Nall, and James Hyslop, “More than Mensing? Revisiting the Question of Fake Scientific Instruments“, Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society, No. 132 (March 2017): 22-29. Available online via open access.)

Find out more about the methods used in this blog by Nall: Finding the Fakes.