What do you do when you mount an exhibition – and then close for lockdown two days later? Pivot online, of course!

If these past months have taught us anything, it’s been the sheer power and potential of digital to reach audiences both old and new. But for small museums, without large teams to strategise or resources to draw upon, a digital turn can feel slightly daunting. Here’s the story of how we at the Museum of Classical Archaeology (MOCA) turned our current exhibition, Illustrating Ancient History: Bringing the Past to the Present, into an online version in just a week or two.

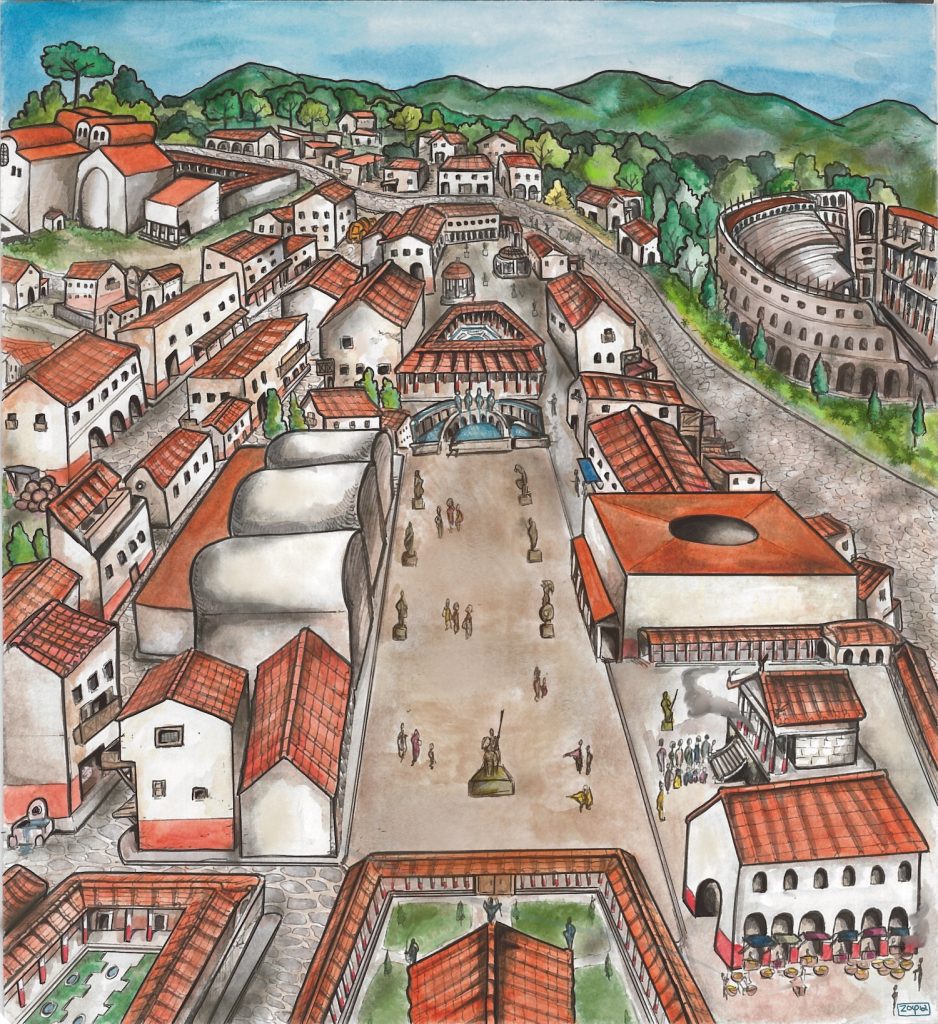

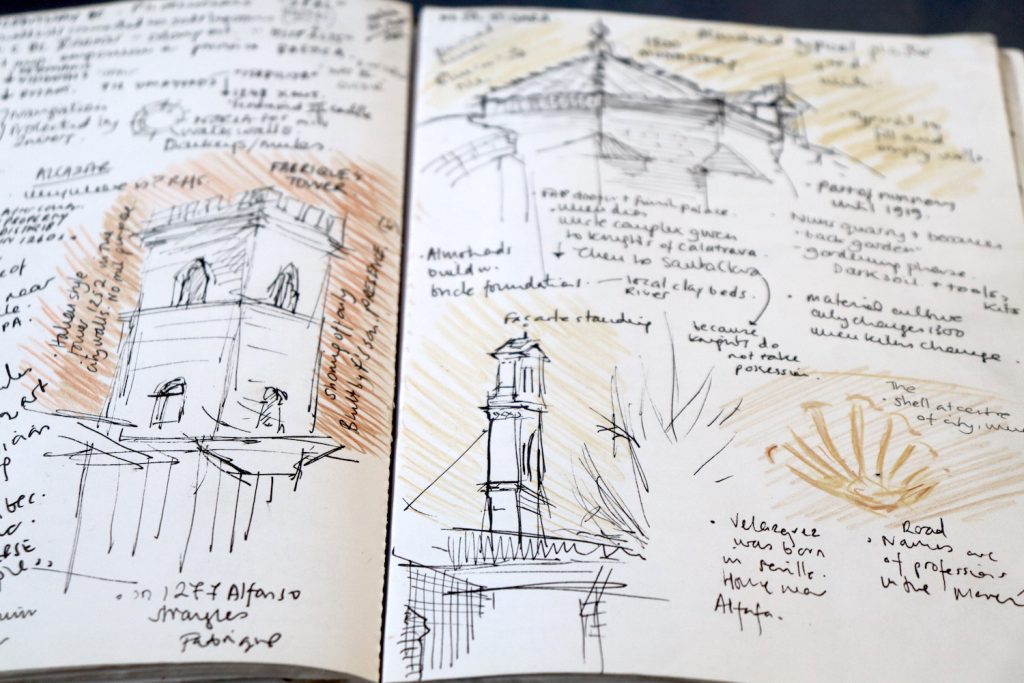

Illustrating Ancient History explores the role images (technical drawings, artist’s reconstructions and beyond) play in bringing the world of an archaeological dig to life for scholarly audiences as well as local communities. The illustrations featured in the exhibition range from pot profiles produced for publication to bright and colourful imaginings of life at Aeclanum, a Roman site in Southern Italy. The aim is to interrogate not only the role and methods of public archaeology, but how archaeological investigation can use visual images to present information to communities and other non-specialist audiences (including families and children).

Importantly, Illustrating Ancient History is research-led: exhibitions are one of the ways through which, as a small university museum embedded in a faculty, MOCA can support the activity of our academics, providing a gateway to the public for access to active research currently being undertaken in Classics and Classical Archaeology. Some of the research questions behind this exhibition do not have easy answers. How can archaeologists help people see archaeological sites and remains, especially when what comes out of the ground are often confusing and overlapping? What responsibilities does the archaeologist have when they present the past, and how can they communicate their own choices when they choose which stories to privilege over others?

The exhibition was curated by Dr Javier Martínez Jiménez, who is a postdoctoral researcher on the Impact of the Ancient City project, led by Prof Andrew Wallace-Hadrill and funded by the European Research Council. The project examines the impact of the Greco-Roman city on subsequent urban history in both Europe and the Islamic World.

If that weren’t enough, the exhibition features the city of Aeclanum and, in particular, the outreach material produced as part of the Aeclanum Project, a collaboration undertaking ongoing excavation between the University of Edinburgh and the Apolline project. The artwork featured in the exhibition was created by Zofia Guertin and Sofia Greaves, both of whom are not only artists but also Ph.D. researchers at the University of St Andrews and the University of Cambridge respectively.

There is, in other words, a lot of research knowledge sitting behind the panels we mounted on Monday 2 November – and a good deal of passion and talent for communicating archaeological discoveries to the public, too. But don’t take it from me! Let me quote the opening display panel instead:

‘Archaeologists play a very important role as intermediaries between the past and the public. They explain buried remains (which are often illegible to the untrained eye!) in a manner which is relatable and can be understood. Images are essential to this process.’

But who was going to see these images? By Thursday 5 November, just two days after unveiling the exhibition, we were closed to the public as England went into its second lockdown.

We knew we didn’t want the exhibition to languish unseen behind closed doors – so our Museum and Collections Assistant, Sade Ojelade, got to work. We had never made an online exhibition, but we knew it was possible: back in December last year (it feels like another world, doesn’t it?), the University of Cambridge Museums team turned our Goddesses, by Marian Maguire show into an online exhibition using the platform Shorthand. Our simplest option, this time around, would probably have been to drop the copy into a webpage on our website. The content was already written, after all: we had the images featured and permission to use them, plus the information from the interpretation panels, labels for individual labels and the text from the accompanying leaflet. But Shorthand gave us greater flexibility, with the option of adding design features that would really showcase the artwork at the heart of the exhibition and without the distraction of sidebars. We were also able to supplement with installation photographs of the works on display, to give a sense of the exhibition in situ.

Transforming an exhibition designed for the walls into something which works online wasn’t quite as straightforward as we might be making it sound, though. ‘After watching an hour-long introduction to Shorthand, an interface that at first fuelled confusion began to make a whole lot more sense,’ says Sade. ‘Once I began, I found limitations in hosting an exhibition with so much content, requiring a lot of workarounds and experimenting. However, its strengths outweigh the difficulties by a mile, producing a final product that does justice to the hard work and wonderful artwork that went into the physical offering.’

(Copyright: Zofia Guertin)

What have we learnt from this process? We’ve learnt that making an online exhibition isn’t really all that different to making an in-person one – all the groundwork had already been laid, we just needed to frame it slightly differently. We also learnt it’s not as simple as just throwing the content into a webpage and pressing publish: narrative structure matters, and it takes dedicated time and energy, so we should probably incorporate online exhibition planning into our regular exhibition planning in future.

But we also learnt that, even as a small team, online exhibitions are within our scope – and this realisation is empowering, because it means we’re opening new doors to widening our digital reach. Who knows what we might do next? Maybe we’ll turn some of our previous exhibitions into online versions, so that they can have a new lift online, long after we packed them up and sent them on our way. Maybe we’ll find ways to incorporate new audiences, or to present our permanent collection through a different lens.

But first? We’ll probably make a cup of tea and concentrate on reopening. After all, the online version of Illustrating Ancient History isn’t a replacement for experiencing the exhibition in person, in dialogue with our plaster casts (which themselves engage directly with questions of how to re-present archaeological discoveries); it’s a supplement.

We’re reopening on Tuesday 8 December, with tickets available from Tuesday 1 December. Why not come and see it for yourselves? Book here