David Farrell-Banks, the Participatory Research and Impact Coordinator at the Fitzwilliam, chats with Sara Hany Abed, a museum and heritage content researcher based in Alexandria Egypt.

Since 2019 Sara has worked with Helen Strudwick, Senior Curator, Ancient Nile Valley at the Fitzwilliam Museum, on the Egyptian Coffins project, pop-up museums, and more. David lets us listen in on their chat…

David: Hi Sara, can you tell us a little bit more about the pop-up museum project and how this ended up in Egypt?

Sara: Working with the Fitzwilliam Museum on the Ancient Coffins project has led to new opportunities for collaboration here in Egypt, including with the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, the National Museum in Alexandria and the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir. The main development was to explore using pop-up museums.

These pop-up museums are about taking museum researchers, objects, replicas, and activities out to communities who might not otherwise have access to the work. A mini-museum can then ‘pop-up’ in unexpected locations. In the work that Helen Strudwick had led in places like Wisbech in 2019 this included pubs, supermarkets, and food banks.

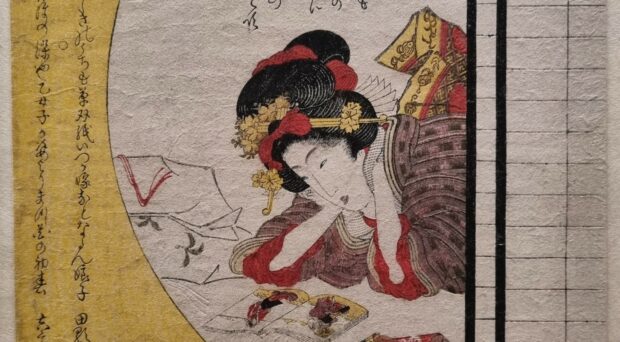

Using the same model, we’ve been taking research, including the work on the Nespawershefyt coffin set that’s displayed at the Fitzwilliam Museum, to the general public in Egypt in new ways. It’s been about exploring different ways of engaging with communities and creating a connection between people and museums. The goal is that museums are not just dry, academic institutions, but something that can go out to people beyond the museum walls.

David: Sounds interesting! What kind of things have you been getting up to in your sessions? Any unusual venues?

Sara: Well, we have been working with furniture and woodwork designers in the city of Damietta in northern Egypt. Damietta is the hub of woodwork in Egypt; Egyptologists and conservators from the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir were able to go to a furniture factory here and run a pop-up museum.

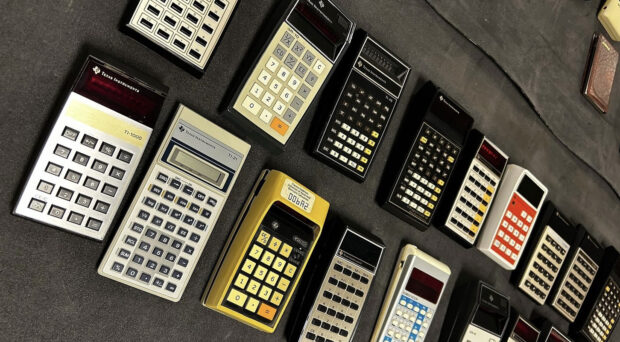

We demonstrated some replicas of ancient Egyptian carpentry tools and had hands-on experiences and discussion about the comparison between the tools that are used now and the tools that were used back then. It was very surprising to know that there are a lot of similarities, that some tools never died out. It’s a living heritage.

In the end, we were having difficulty finishing the pop-ups because more people kept arriving. Someone stayed for almost 8 hours and one of the children who came along told us that:

“this looks like national geographic, but it’s live!”

Hearing something like that is really rewarding.

The pop-up museums let people see the relevance that things have to their own history. And it’s fun, as well. If someone is curious, it’s fun. If people don’t really have fun and enjoy it, then why would we do it?

David: What have you learned from the sessions?

Sara: Highlighting the connections between our museum collections and the practices and way of life which still exist in today’s modern Egypt, humanises the whole experience. It makes it closer on a human level.

The pop-up museums provide us with new forms of knowledge. For example, we can learn more about woodworking practices and incorporate those findings into the galleries in our museums.

It’s how we want people to feel. You can experience objects in a pop-up museum, then, when you go back to the museum you see it in a completely different way. It’s no longer just an object, and I think that’s what we really want.

What’s really great about all of this is that it’s quite endless; one door leads to another, then another, then another… It means it’s been a success because it’s opening doors to other possibilities and ideas, which is really interesting.

David: And what are the next steps for this?

Sara: At the moment, we are running a new series of pop-up museums in Egypt. We would like to extend this and recreate an ancient Egyptian carpentry workshop in Damietta, because although it’s the hub of Egyptian furniture and woodwork, there is no museum related to ancient Egypt in the city.

Then, we will be continuing our work in Cambridge over the coming months. We have already shared data with the education team at the Fitzwilliam and started creating a short film for school visits. All the possibilities that are available when you think about collections differently is really interesting. You can connect the collections to what you have today. It’s not just a dead history, it’s very much alive.

This work was funded through generous grants from the University of Cambridge’s Arts and Humanities Impact Fund and the Global Challenges Research Fund.

For further information about the pop-up museum concept, please see the article by Melanie Pitkin et al. “Engaging audiences in areas of low cultural provision: the concept of the ‘pop-up’ museum experience”, CIPEG Journal no. 4 (2020), 37-53, https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/cipeg/article/view/83936

Find out more about the Fitzwilliam Egyptian Coffin Project and pop-up museum here.