We have always known that Anna Maria, the eldest daughter of Black British abolitionist Olaudah Equiano, died on 31 July 1797 and was buried in Chesterton. However, the exact site of her grave had long been forgotten. This Black History Month blog is the story of our rediscovery of Anna Maria’s grave.

This discovery builds on research initially conducted by Dawnanna Kreeger, an independent Cambridge-based historian, and me for the Fitzwilliam Museum’s 2023 Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance exhibition and its follow-on 2025 show, Rise Up: Resistance, Revolution and Abolition.

Anna Maria Vassa’s short life in Soham

Following their marriage in April 1792, leading Black abolitionist Olaudah Equiano (aka Gustavus Vassa, The African) and his new bride Susannah Cullen decided to remain living in Soham, rather than move to London. Susannah had moved from her native Ely to this thriving Fenland town in the late 1780s or early 1790s, together with her widowed mother and unmarried siblings.

We do not know where ‘Mr and Mrs Vassa’ resided in Soham but it must have been within the parish bounds of St Andrew’s parish church. Thanks to the church’s baptismal register, we know that Anna Maria was born on 16 October 1793, and christened ‘Ann Mary’ (only later was her name Italianised) on 30 January 1794, presumably after her maternal grandmother and maternal aunts.

Image credit: Sue Martin / Cambridgeshire Archives, Ely.

Anna Maria lived in Soham for much of her short life. This is where her sister, Joanna, was born on 11 April 1795 and where her mother sadly died on 16 February 1796, aged 34. Susannah Cullen-Vassa was buried five days later in St Andrew’s Soham churchyard. This hand-tinted etching and aquatint shows the church in 1797, exactly as it was when the Vassa family lived in Soham:

Sadly, for Anna Maria, her father died just over a year later, in London, on 31 March 1797, leaving her and her baby sister orphans. Anna Maria herself died less than four months later on 21 July 1797.

Explaining Anna Maria’s burial place

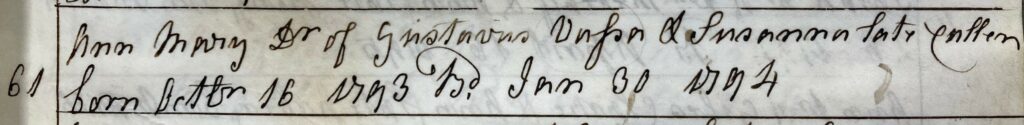

Anna Maria was buried in the churchyard of St Andrew’s, Chesterton, a quiet village north-east of Cambridge. Rather inexplicably, Anna Maria’s burial is not recorded in the relevant burial register of this church:

Image credit: Victoria Avery / Cambridgeshire Archives, Ely.

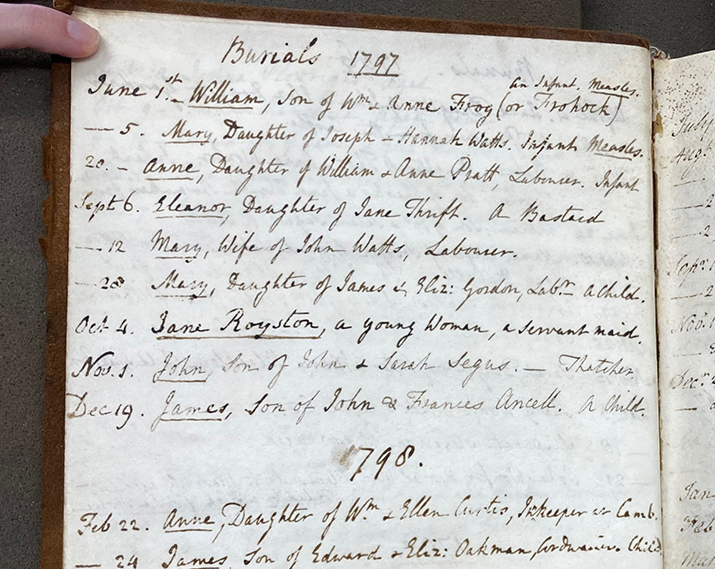

Yet, we know that Anna Maria was definitely buried in the churchyard of St Andrew’s, Chesterton. There is an inscription on a large stone plaque affixed to the church’s exterior north wall:

St Andrew’s Church, Chesterton, exterior north wall.

Image Credit: St Andrew’s, Chesterton / Rev’d Dr Philip Lockley.

Near this Place lies Interred

ANNA MARIA VASSA

Daughter of GUSTAVUS VASSA the AFRICAN.

She died July 21, 1797.

Aged 4 Years [sic].

Should simple village rhymes attract thine eye,

Stranger, as thoughtfully thou passest by,

Know that there lies beside this humble stone,

A child of colour haply not thine own.

Her father born of Afric’s Sun-burnt race,

Torn from his native fields, ah, foul disgrace:

Through various toils, at length to Britain came,

Espous’d, so Heaven ordain’d, an English dame.

And follow’d Christ: their hope two infants dear,

But one, a hapless Orphan, slumbers here.

To bury her the village children came,

And dropp’d choice flowers, and lisp’d her early fame:

And some that lov’d her most, as if unblest,

Bedew’d with tears the white wreath on their breast;

But she is gone and dwells in that abode,

Where some of every clime shall joy in God.

Significantly, the church’s building was previously Grade II* listed, but this was amended to Grade I in 2007 – the bicentenary year of the 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. This was entirely due to the significance recognised in the plaque commemorating Anna Maria, the campaigning achievement of her father Olaudah Equiano, and the church’s consequent links to Black British history.

Why was Anna Maria not buried with her mother in the churchyard of St Andrew’s, Soham; or, indeed, with her father in the churchyard of Whitefield Tabernacle on Tottenham Court Road, London?

Links to Chesterton

Thanks to a 2021 online blog by the Rev’d Nick Moir, a 2022 article by Matthew Abel on ‘Edward Ind (1751–1808): Brewer, Poet, Abolitionist’ (published in Brewery History, vol. 190, pp. 44-61), and contemporaneous research conducted by Dawnanna Kreeger and me for the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Rise Up exhibition, we now know that the author of this unprecedented epitaph was wealthy Cambridge Alderman and brewer Edward Ind, one of the co-executors of Equiano’s will. It also seems likely that Ind funded the commission of the stone memorial from his own pocket.

The plaque proves that, at the time of her death, Anna Maria must have been living within the parish bounds of St Andrew’s, Chesterton, or else she would not have been buried there. Although uncertain, it seems likely that her baby sister, Joanna, was living with her in Chesterton. So why did their guardians choose a foster family in Chesterton, and which family was chosen?

We have concluded, along with Moir and Abel, that the most likely candidate is Thomas Ind, a younger brother of Edward Ind. Thomas is documented as having lived in the parish of St Andrew’s, Chesterton, with his wife, Mary, and their two small sons. Perhaps these boys were the village children referred to in the epitaph, who laid flowers on Anna Maria’s grave?

Although the epitaph clearly stated that Anna Maria had been interred ‘near this place’ and ‘beside this humble stone’, the precise location of her grave had been lost in the mists of time.

The rediscovery of Anna Maria Vassa’s grave

The rediscovery of Anna Maria’s grave on 30 September 2025 was entirely serendipitous and extremely timely. It was the day before Dawnanna and I had planned to submit the final version of our forthcoming article on ‘Equiano’s Cambridgeshire family’ and the start of Black History Month 2025; a week before our talk on ‘Olaudah Equiano’s Cambridgeshire Family’ (the St Andrew’s Soham Black History Month Annual Lecture 2025); a fortnight before Anna Maria’s 232nd birthday; and three weeks before a planned community event at St Andrew’s Chesterton, to update everyone on The Equiano Family Project. For further details, see my related blog: Celebrating Equiano’s Cambridge connections.

For a few days before the intended submission date, I had what can only be described as a light-bulb moment. I remembered consulting and photographing in 2021 the typed manuscript of an A-Level essay written nearly 50 years ago in 1977, in the Peter Peckard papers at Magdalene College Archive, when I was there in search of Equiano material to include in the Black Atlantic and Rise Up exhibitions.

In my mind’s eye was the very clear image of a photograph of a grave at the end of that essay that had some connection to Anna Maria Vassa. So strong was this image that I was compelled to go back through several thousand photos to relocate those taken during my visit. Amongst them, I found my snaps of this A-Level essay: ‘The Early Cambridge Campaign against Slavery (1780–1790)’ by Catherine O’Neill of St Mary’s School, Cambridge.

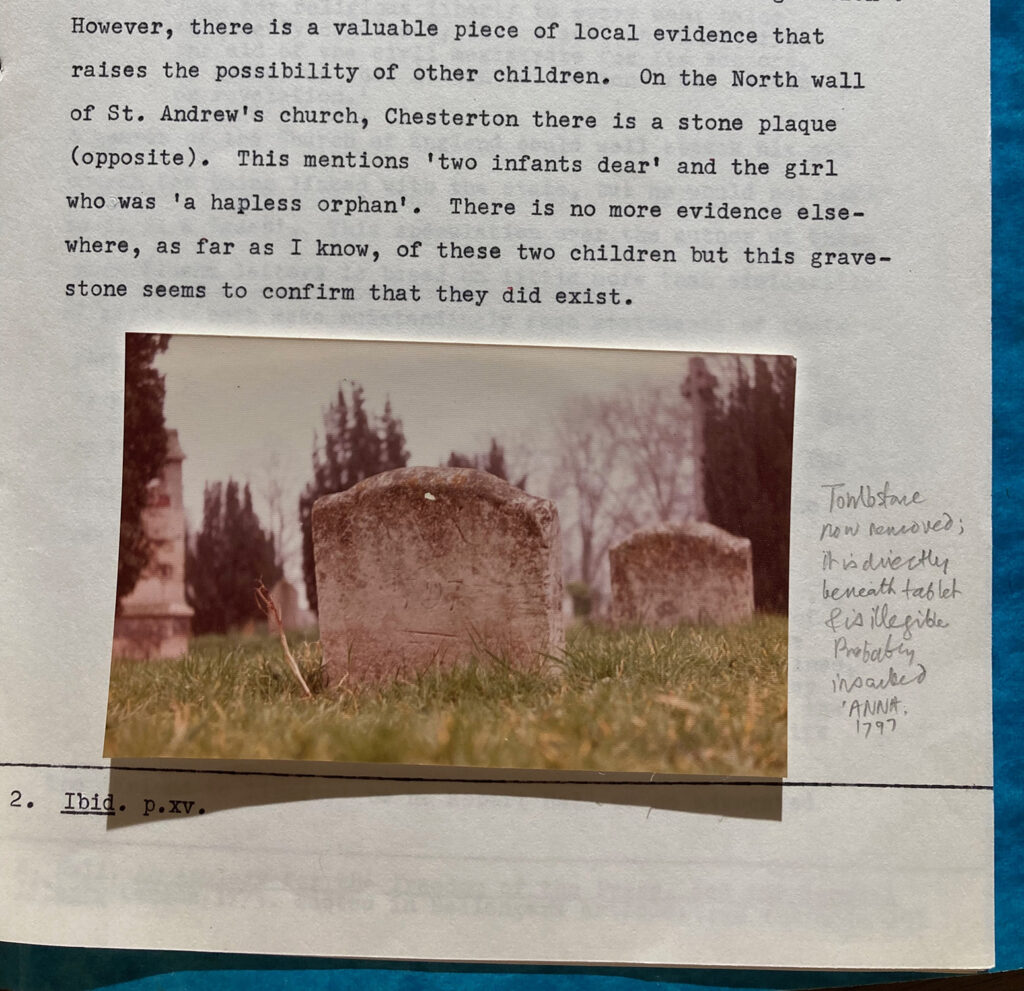

O’Neill’s essay concluded with a two page appendix dedicated to ‘Equiano’s Children’. After two sentences referring to the large stone epitaph on the church’s north wall commemorating Anna Maria’s life, the final sentence states, ‘There is no more evidence elsewhere, as far as I know, of these two children but this gravestone seems to confirm that they did exist’. Underneath this was a photo of a gravestone with an illegible inscription.

O’Neill’s list of illustrations at the start of her essay captioned the epitaph as ‘The plaque in Chesterton churchyard of Equiano’s daughter’, and the gravestone as ‘Her gravestone nearby’. Although O’Neill’s text offered no further explanations, Dr Ronald Hyam, Emeritus Archivist at Magdalene, later added in pencil the following comment into the margin: ‘Tombstone now removed; it is directly beneath tablet & is illegible. Probably inscribed ‘ANNA 1797.’ This was too much to ignore!

Armed with these intriguing visual and textual clues, I was determined to get to the bottom of this half-century old puzzle. I contacted Rev’d Dr Philip Lockley, vicar of St Andrew’s, Chesterton, and asked him if a stone resembling that in O’Neill’s 1977 photo was still in place, close to the stone epitaph, following the visual clues in the old photo (portion of church porch, standing cross and yews, etc.).

Philip got back very quickly with a possible match. Given the illegibility of the inscription (despite several photos and a rubbing) and the absence of the second stone shown in the background of O’Neill’s photograph, he asked us to pop over to the churchyard so we could verify independently and in person.

A serendipitous sighting

The only day Dawnanna and I could visit was Tuesday 30 September, when the weather was glorious, unlike the endless run of dank and dismal days before and afterwards. Moreover, due to unforeseen circumstances, we arrived an hour later than planned, which was a blessing in disguise. By the time we located the grave, we had optimal viewing conditions. The sun shone directly onto the gravestone at the perfect intensity and ideal angle for its very worn lettering to be exceptionally legible.

This allowed us to ascertain that its brief inscription did not read ‘ANNA 1797’ as Dr Hyam’s pencil notes had suggested, but rather ‘AMV 1797’. In other words, Anna Maria Vassa’s initials and the year of her death. Given the stone’s acute downward-facing position, without this precisely angled ‘heavenly spotlight’, we would never have been able to read the inscription. This explains why it has gone unnoticed since Cathy O’Neill’s suggestion of 1977. It was very much a case of ‘being in the right place, at the right time’!

Hidden in plain sight

The particular combination of initials and date indicate that this stone was made to commemorate the final resting place of Anna Maria Vassa. No one else with those initials was buried in St Andrew’s Chesterton that year. Moreover, as Dawnanna pointed out, the small dimensions of the stone and the use of initials prove that this was the footstone of her grave, rather than its headstone.

After all, according to late eighteenth-century conventions, the latter would have been larger and inscribed with a longer inscription, likely giving at least her full name, parentage and full date of death. Whether Anna Maria’s grave was ever adorned with a headstone requires further research, but her guardians may well have felt that the large stone epitaph on the church façade nearby was sufficient.

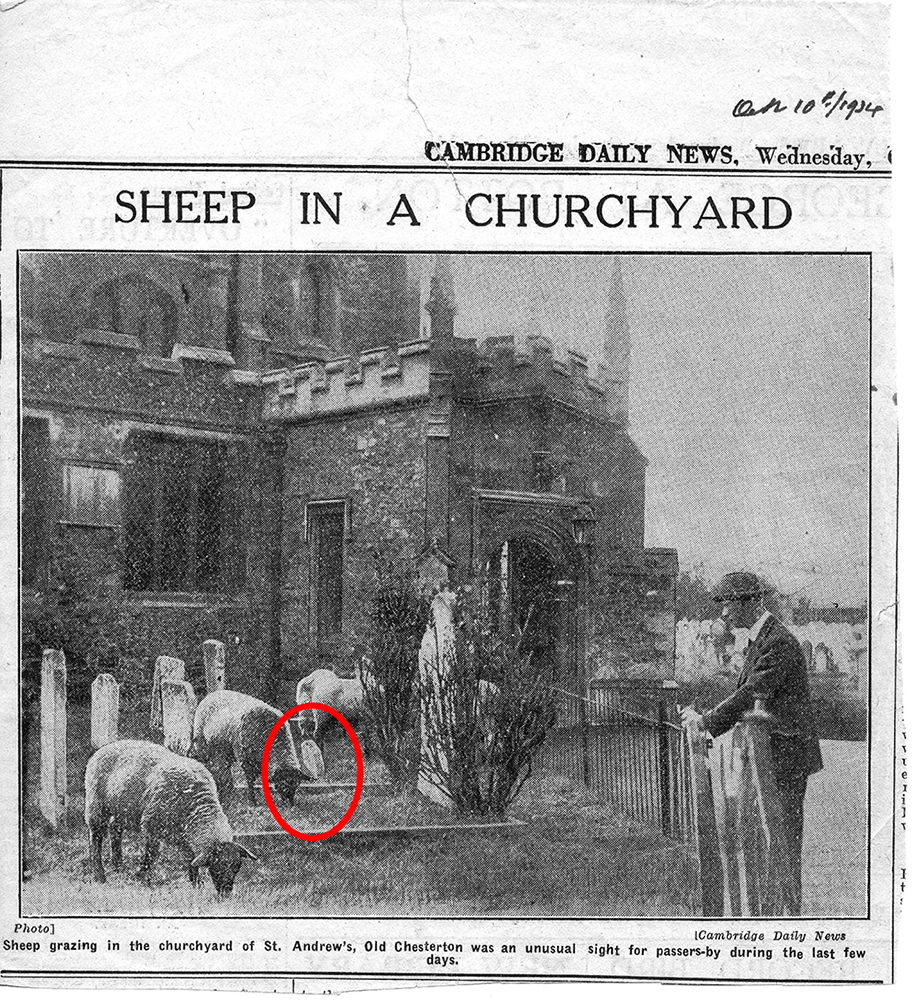

Following our rediscovery, Rev’d Lockley kindly sought out historic photographs of the churchyard. He discovered one from October 1934, which showed the footstone occupying the same location as it does today.

Image credit: Rev’d Dr Philip Lockley.

Indeed, while other nearby gravestones have clearly been moved to make way for a new path, there is no evidence to suggest that Anna Maria Vassa’s footstone has ever been moved. Assuming that it is, indeed, in its original location, we now know for certain where Anna Maria is buried, thereby solving an historic conundrum.

It also explains the precise placement of the epitaph on the church’s exterior north wall, which had previously been regarded as curious, as it was standard practice for wall-mounted funerary inscriptions to be placed inside churches.

The traditional explanation was that Anna Maria had been raised Nonconformist and, as such, a memorial inside the church would have been considered inappropriate. While this may have some truth in it, our rediscovery of Anna Maria’s grave – lying directly in front of the epitaph and only a few feet away – is surely the real reason.

We can therefore now conclude that the large and unmissable epitaph was deliberately positioned to ensure that passersby did not miss the nearby grave, which might otherwise have been overlooked, especially if marked only by a footstone.

The location of Anna Maria’s grave so close to her epitaph should not, perhaps, come as any surprise given that it records, ‘Near this Place lies Interred Anna Maria Vassa’ and also ‘Know that there lies beside this humble stone, a child of colour’. What is more surprising, perhaps, is that her grave has been hidden in plain sight for so long. Without that beam of celestial light just when we needed it, it is likely that the precise location of Anna Maria’s corporeal remains would remain unknown.

In a final act of synchronicity, I was able to establish a connection with Catherine O’Neill, author of the 1977 essay. She had been a brilliant and much-loved English teacher at St Paul’s Girls’ School, Hammersmith, when I had been a pupil there in the 1980s. Through another beloved teacher, who was still in touch with her, I have now been able to reconnect with Cathy, and thank her for her essay. Nearly 50 years after she wrote it, the essay provided the impetus for the rediscovery.

Sharing the ‘breaking news’ with local communities

The timing of our rediscovery was perfect as it meant we could squeeze it into our article and share it with local communities in both Soham and Chesterton. We were able to weave the ‘breaking news’ into our evening talk on ‘Olaudah Equiano’s Cambridgeshire Family’ that we gave with Dr Carol Brown-Leonardi (Open University; Founder and Chair of the African Caribbean Research Group, Cambridge; and Legacies of Windrush in Cambridgeshire Project Lead) at St Andrew’s, Soham, on 8 October as part of the church’s Black History Month annual lecture series.

And, the rediscovery announcement became part of the Anna Maria Vassa Commemoration event at St Andrew’s Chesterton, already scheduled for Saturday 18 October. This had been organised by Rev’d Dr Philip Lockley and Rev’d Eleanor Whalley, vicars of the sister parishes of St Andrew’s Chesterton and St Andrew’s Soham, to update the local community about the Equiano Family Project.

Community commemoration

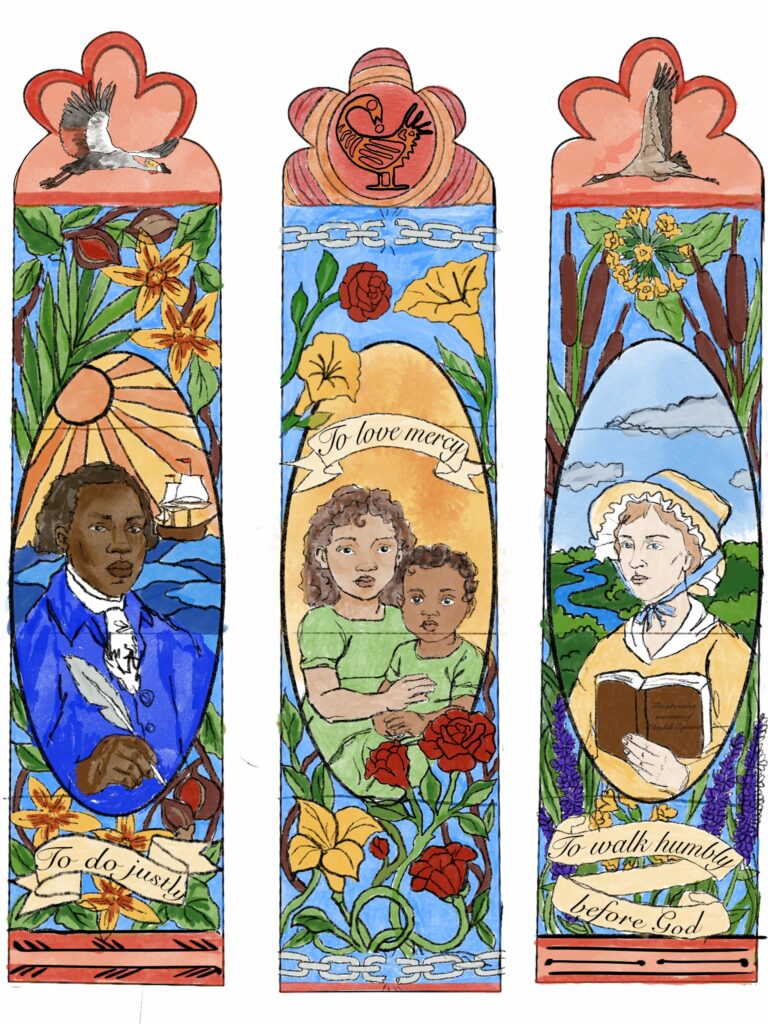

Rev’d Lockley was able to share with participants that the artist chosen to create the new stained glass window adjacent to the stone epitaph is Selena Scott, former University of Cambridge Museums Celebrating Black History in Cambridge Project intern (yet more synchronicity!). Selena explained, via a video, her design and the choices behind its iconography. I was invited to say a few words about the rediscovery of Anna Maria’s grave.

After the indoor presentation, there was an act of communal commemoration around Anna Maria’s grave with a welcome and introduction by Rev’d Lockley. Carol Brown-Leonardi read the words of Anna Maria’s epitaph, alongside some words from Equiano’s autobiography selected and read by Isaac Ayamba. Sitara Amin-Priddle read a short passage from scripture, ‘to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly before God’ (Micah 6:8). These had been quoted by Equiano at the end of his autobiography:

‘I early accustomed myself to look for the hand of God in the minutest occurrence, and to learn from it a lesson of morality and religion […] Afterall, what makes any event important, unless by its observation we become better and wiser, and learn “to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly before God?”.’

This poignant event ended with this group photograph under the stone epitaph, with Anna Maria’s grave strewn with flowers in the foreground. Subject to securing the necessary funding and permissions, Selena’s new stained glass design will be installed next year.

Read Victoria Avery and Dawnanna Kreeger’s 2025 full article in the Women’s History Review.

To find out more about the Equiano Family Project, and how you can support it, visit St Andrew’s Chesterton website.