The Fitzwilliam Museum has been thinking about tactile access to collections for a long time.

From touch tours for the blind and partially sighted to education seminars for students, the Museum understands that touch can offer a fantastic opportunity to learn from and enjoy the collections.

Working in Collections Care, I am approaching this topic from a slightly different angle; I am interested in how we can ensure the Museum’s collections are not at risk of damage (think: ‘Please Do Not Touch’ signs), while still keeping a large amount of the pieces on open display and continuing to offer tactile experiences.

The Cambridge Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Doctoral Training Partnership provided an opportunity that seemed too good to miss, called ThinkLab. The Museum was given access to the research skills and time of thirteen PhD students to focus on one particular question. Here, one of the students, Katherine Dixon, explains how the project panned out.

Introducing ThinkLab

“In recent months, the Fitzwilliam Museum has been collaborating with PhD students from the University of Cambridge in a project called ThinkLab. ThinkLab provides organisations with a research model that gives them the chance to reflect on a burning question outside of the usual constraints of day-to-day operations, supported by the creativity and research expertise of PhD students in the Arts and Humanities. The issue at hand this time: What provision can the Museum offer to its visitors by way of alternative tactile experiences that also maintain its preservation principles?

The project

“Over an intensive period of two months between October-November 2018, a diverse group of PhD students – with research backgrounds varying from Art History to Archaeology, French Literature to Education – worked with the Fitzwilliam Museum to develop answers to its questions about touch.

“For the PhD researchers like me, ThinkLab started with an application. We were presented with the Fitzwilliam’s question and asked to explain our personal and professional interests in the project and the specialist skills we could contribute to the investigation. For me, I had two main motivations for working with the Museum. These were, firstly, the chance to gain experience in outward-facing academic research and, secondly, the opportunity to consider the role that digitisation and the digital humanities, topics about which I am deeply enthused, could play within the Fitzwilliam’s curatorial practice.

“To start, we were briefed by staff at the Fitzwilliam to research evidence-driven alternatives and analogues to the Museum’s ‘Do Not Touch’ policy for the artefacts it has on exhibit. This is part of a larger enquiry that is currently underway at the Museum that seeks to understand the efficacy of different display methods to discourage visitors to touch vulnerable artefacts in the Fitzwilliam collection.

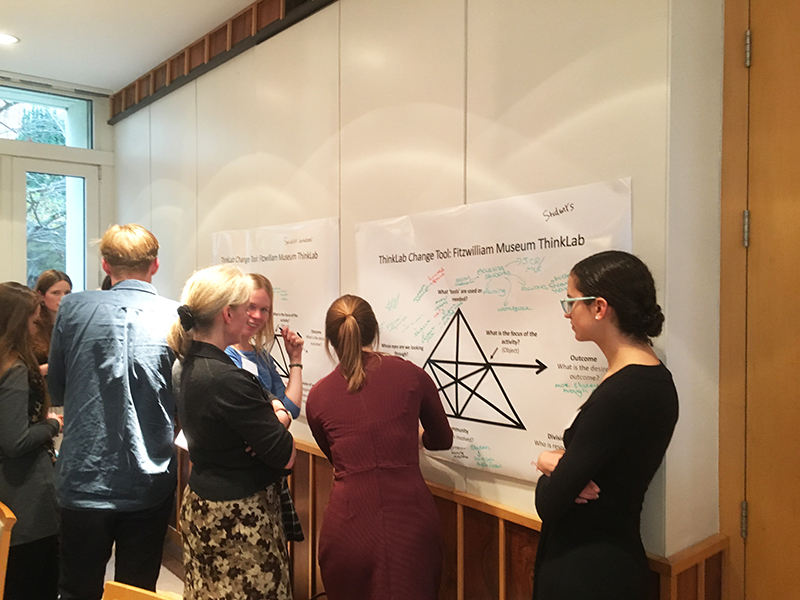

“By applying the ThinkLab model in a research programme devised by the University of Cambridge, students and museum staff members sought to investigate the role of touch in the museum environment as well as how it might contribute to visitor engagement and enjoyment. Upon meeting with museum representatives from its conservation, curatorial, education and management teams, it was immediately apparent to us that the outcomes of this research would resonate with an array of departments at the Fitzwilliam. So too, it was clear that any changes to museum practice that the ThinkLab team could propose would, crucially, have to be sure to take its preservation principles into account.

What we did

“Following initial consultation with the Fitzwilliam, students split into three focus groups so that we could investigate three different visitor groups and the specificities of their visitor experience as concerns the issue of touch. These groups were: university undergraduates, non-native English speakers and visitors with a personal or professional connection to museum items (this category encompassing a vast spectrum of visitors, including religious visitors, migrants, artisans and academics).

“Meeting weekly, students conducted fast-paced, but nonetheless highly rigorous, research into their chosen topic areas and were able to liaise with the Fitzwilliam team throughout the process to enable access to relevant museum data and to gain additional insights into museum practice. In just four weeks, we compiled and analysed data from over 300 surveys, completed audits of museum resources and facilities, interviewed numerous community stakeholders and prepared relevant case studies of other institutions, both in the UK and internationally, which had implemented excellent initiatives to offer tactile experiences to their visitors.

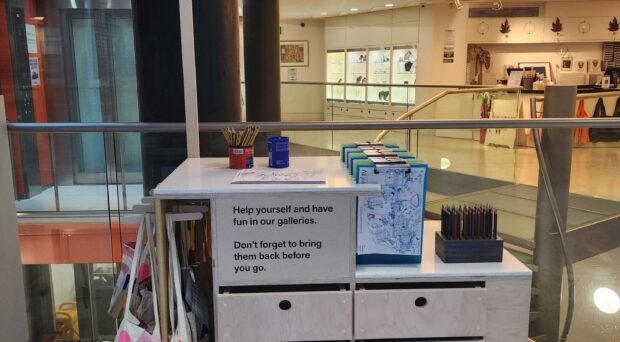

“This research culminated in an away day for both students and Fitzwilliam staff. Students presented their findings to the Fitzwilliam team and, over the course of the day, the group as a whole began to excitedly identify key areas to focus on improving and new ideas to consider implementing. These ranged from small but impactful changes, such as making alterations to museum signage, tweaking the Museum’s communications strategy for its student audience and updating and expanding its array of educational resources, to more significant shifts in museum practice, for instance working to make the conservation process visible to visitors and the option of facilitating religious engagement with certain museum objects. The event was also an excellent opportunity for the students and the Fitzwilliam team alike to showcase their skills and capacities and to share knowledge and advice on topics varying from curatorial practice and digitisation initiatives to tactics for student engagement and sociological theories of the museum space.

The outcome

“By the end of the ThinkLab process, the group had agreed on three main areas upon which to focus going forward: unveiling the conservation process, integrating the Museum more successfully into student life – both academically and socially – and designing customised trails and tours that incorporate sensory experiences. The Fitzwilliam team departed equipped with a practical, achievable plan of action to improve the Museum’s tactile provision for many different types of visitor without compromising its rare, fragile and/or valuable collections.

“Personally, I left enthused by the quality and quantity of productive solutions to a research problem that can be developed in a short space of time when inspired by a fascinating question and offered the time and space to think creatively about it. The opportunities to collaborate as a PhD student in the Arts, either with one’s peers or other professionals, are few and far between so I found it hugely rewarding to develop new connections in and beyond the university and to work towards a goal in a team. It has been an important chance for me, and I know the same is true of my fellow students, to understand the role that my skills as a postgraduate can play beyond the academic sphere and this has opened my eyes to different career options in the future. I have also forged valuable professional connections at the Museum, witnessed the dedication with which the Fitzwilliam seeks to enhance the experience of its visitors and gained insight into the many varieties of professions and expertise required to operate such an institution.”

What’s next?

For any organisation, it can be extremely beneficial to get some outside perspectives. ThinkLab not only gave the Museum a wealth of knowledge and research from the students but acted as a catalyst for further discussion about how we might be able to improve our offer to visitors. In January, we aim to hold a wider discussion forum for lots more of the Fitzwilliam Museum staff to hear about the students’ research. From there, we hope to have a better idea as to what could be feasible and what might be possible to take forward. Watch this space…