The Her Story project’s latest venture takes us to the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Founder’s Library. This beautiful high-ceilinged room is full of treasures – including a set of personal letters from author Charlotte Brontë to her friend and former headmistress Margaret Wooler.

Brontë, the author of Jane Eyre, is one of the giants of nineteenth-century literature. The Fitzwilliam’s letters unlock a network of women, all of them – in different ways – wrestling with the problem of having a voice as authors and thinkers in their own right. They cover the tragic deaths of Brontë’s sisters, authors Emily and Anne, and brother Branwell; her struggles with her publishers; skirmishes with fellow writer Harriet Martineau; and her eventual, conflicted decision to marry. They have strongly influenced how we think about Charlotte Brontë, thanks to their use by Elizabeth Gaskell as a source for her biography: the first full-length biography of a female novelist written by one of her fellows.

And yet they may have been subject to censorship. The physical state of the letters reveal how contested Brontë’s legacy was. Missing pages suggest that, after her death, traces of her struggles with severe depression and mental ill-health were removed from her official biography.

We met with Suzanne Reynolds, Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts and Printed Books, to find out more…

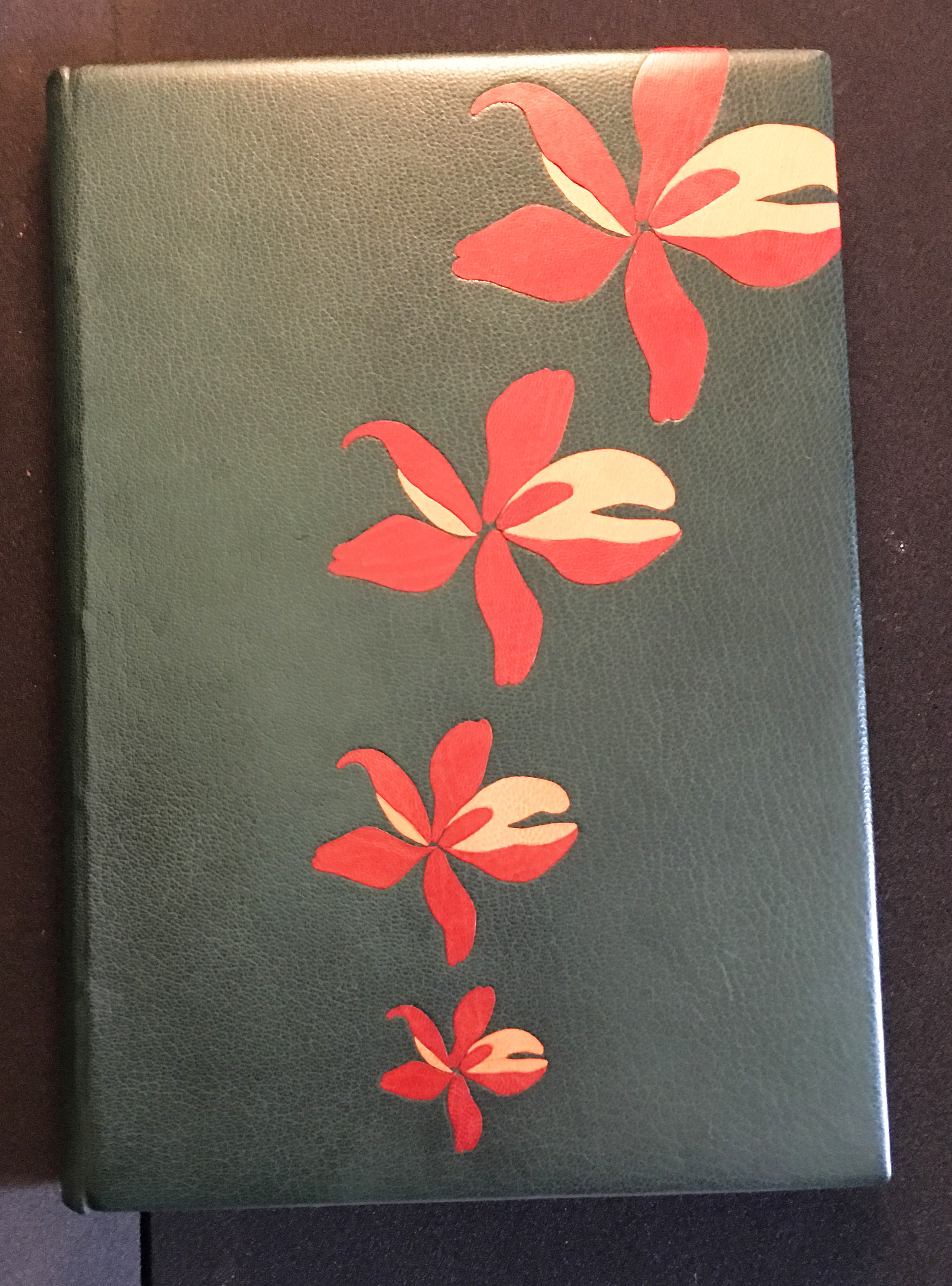

Hello Suzanne. Is it normal for letters to be bound like this?

This group of letters was only bound about ten years ago. It’s really for reasons of preservation – letters are very ephemeral, and it’s very easy for them to “escape” – and the decision to bind them comes from their museum setting. They have been bound in such a way, on Japanese paper, that they’re very easy to take one out without harming them.

It’s a very Fitzwilliam thing to do, and it’s a museum way of treating literary remains. It’s not what you would find if they were housed in archives or even the British Library; they would be preserved as separate leaves. The pattern was established here at the Fitz by Sydney Cockerell, who was Director for much of the first half of the twentieth century, when the letters came into the museum’s collection. They were given to the museum by Sir Clifford Albutt, Miss Wooler’s great nephew.

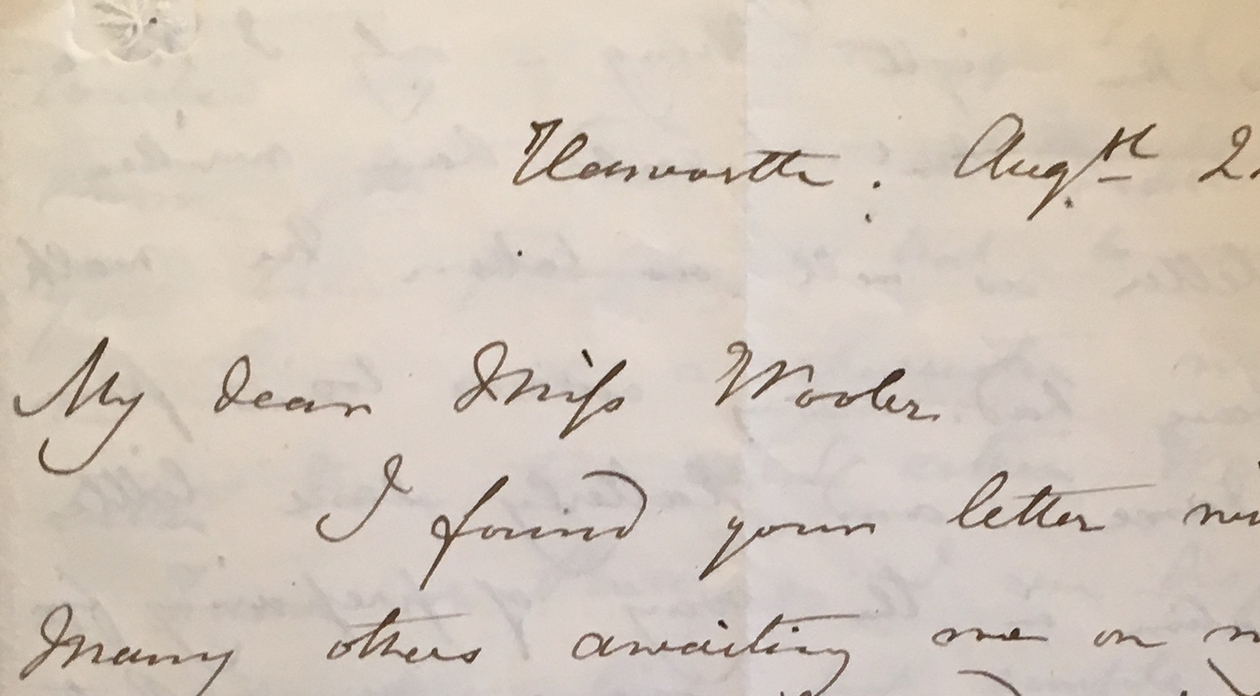

It’s a thrill to see Brontë’s own handwriting close up: it brings you so close to her.

Ah, well – it’s interesting you say that. At this period, you were taught to write in a very particular way, so there isn’t perhaps as much distinction between people’s handwriting as there is now. But she does write in this very beautiful copperplate style. It’s very neat, it’s very small. Having said that, there’s a contrast with the one letter in the collection by Mrs Gaskell. Her handwriting is much bolder, and much heavier on the paper. I don’t know if you can say it’s more confident, but it’s certainly a more bold hand.

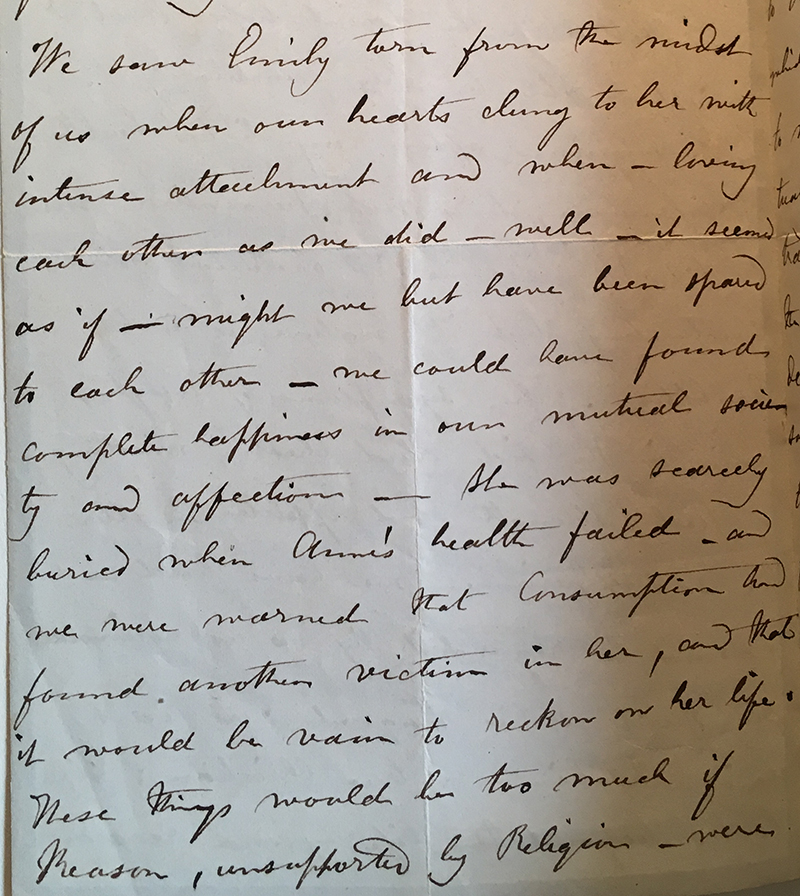

As in many different aspects of her life, Charlotte Brontë creates a surface impression that everything she does is highly considered. Her handwriting is like that: it’s very neat and controlled. But then there are moments in these letters where the control and the syntax breaks down.

“We saw Emily torn from the midst of us when our hearts clung to her with intense attachment and when – loving each other as we did – well – it seemed as if – might we but have been spared to each other – we could have found complete happiness in our mutual society and affection – she was scarcely buried when Anne’s health failed.” (Letter 6)

It’s a very powerful moment. Where normally she writes very beautiful, controlled sentences, this is just a series of desperate thoughts piled one after the other, separated with hyphens. It’s very hard to read.

Like quite a few of the letters in the collection, this one is written on mourning paper, paper edged in black. It was written in March 1849 in the aftermath of Branwell’s death, and Emily’s death, and the horrible realisation that Anne was not going to pull through.

She says we “could” have found complete happiness… Does that suggest that their relationship was quite difficult at times?

They were all incredibly close. They were brought up in a parsonage where they didn’t see any other children. They were all born one year after the other, and their relationship was incredibly intense. They created amazing fictional worlds together, but they were still very, very different people. I think Emily was an extraordinary character. There’s one letter at the beginning of the collection where she seems to have been a bit of a financial wizard, manipulating their shares in the rail companies. And this is also a girl who intervened to separate physically two dogs savagely attacking each other when others stood by in fear. Charlotte was on the surface far more conventional. She was able to operate in the world in a way Emily never could.

There are little hints in the letters – like the railroad shares – that the world is changing. Charlotte visits the Great Exhibition in London five times, taking the train down from Yorkshire. There’s a struggle with where you sit in this new world as a woman. What’s your role? I was intrigued that Charlotte says to Miss Wooler that, as a single woman she has worked hard as a teacher and now she is “free”.

Yes, there are a couple of letters that speak in really admiring terms to Miss Wooler, who had been Charlotte’s teacher and then employer when Charlotte herself taught, about how she’s a model for forging a respectable life alone in the world, and how it takes courage and fortitude and balance.

“You worked hard, you denied yourself all pleasure, almost all relaxation in your youth and the prime of your life – now you are free…” (Letter 2)

We have to proceed with caution though; what we see in the different sets of letters that Brontë writes to different correspondents are different aspects of her personality. Here, in this correspondence with her mentor, she’s the dutiful daughter, dutiful teacher. So in that sense there’s bound to be approval of Miss Wooler’s path. But what we also see in the course of the letters is that that path is changing. By the end of the collection she is married and has chosen a very different avenue.

Brontë married clergyman Arthur Bell Nichols in June 1854. Miss Wooler escorted her down the aisle, after her father refused to attend at the last minute.

It was a desperately difficult choice, and obviously one she feels very conflicted about. Partly it was done to secure her father’s future, rather than for her own happiness, although it seems to have turned out that she was happy. That’s a tension the whole way through the letters: finding my path. Is my path going to be a solitary one? Is it going to be as a writer? Money is another concern that keeps coming up: can I support myself? And then we have a turn into a different sort of life at the end.

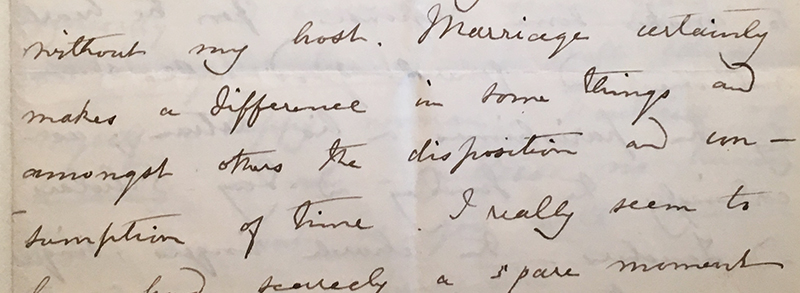

Once married, she says, ‘my time is no longer my own’…

Yes, and that’s a very interesting letter at the end, where you see that she’s throwing herself into this new very active, practical life. There’s one sentence where I think a slight fear escapes.

“The fact is, my time is no longer my own now; somebody else wants a good portion of it – and says we must do so and so. We do “so and so” accordingly, and it generally seems the right thing – only I sometimes wish that I could have taken the letter as well as taken the walk.” (Letter 29).

I think there’s no doubt that actually she was happy, but she already was working on another novel at this point, which would have been called Emma. It’s very intriguing to wonder if she would ever have been able to finish that, or whether Arthur Bell Nicholls would have encouraged her to continue publishing. His actions after her death suggest that he may not have done.

The correspondence ends with Brontë’s death, the year after her marriage, in 1855. Was Bell against Gaskell writing the biography?

Bell seems to have been a very proud husband, but a very possessive one. And as happens with many writers after their death, there was a battle for her memory, her story. What I find very interesting is that the letters are all very beautifully bound and presented here, but some of them are very fragmentary. Some are one page only, some have the second page but not the first. Often those are the letters where she’s starting to talk about depression, uncertainty, ill-health. It seems as if they have been censored. We get a very different side of Charlotte Brontë in her letters to her friend Ellen Nussey than we get in this ‘dutiful daughter’ set, and Nicholls was really desperate that Nussey destroy them. He was very angry with the Gaskell biography because it quoted heavily from the Nussey letters, and he refused to let Gaskell see a lot of material, including Brontë’s juvenilia. There really was a battle after her death about how to create the legacy, and how to write her life.

It’s that tension, that questioning that we see in the letters acting out on her legacy: where is my place: am I a wife and daughter, am I a writer? Can I be both?

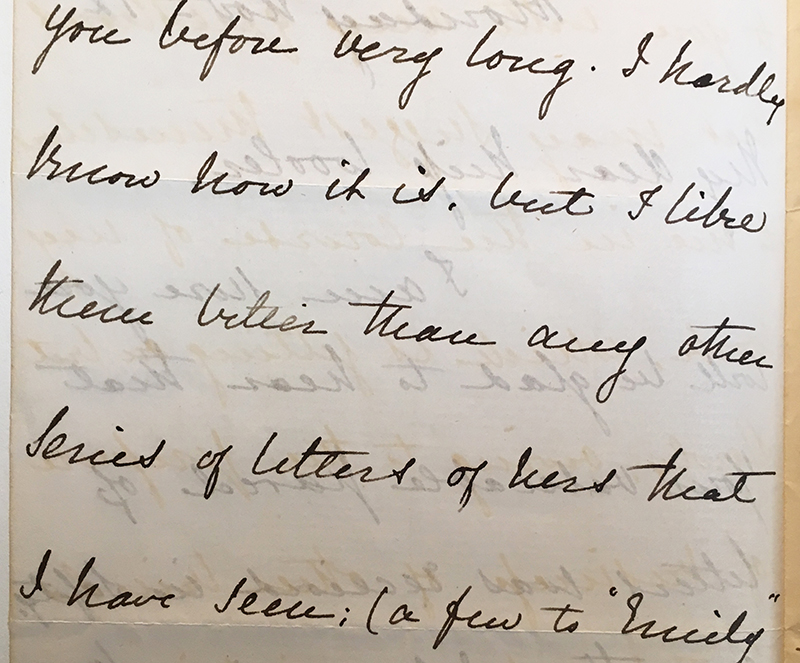

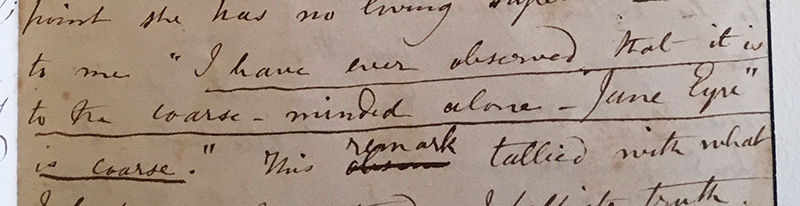

It is. In the letter included at the end, Mrs Gaskell says, “I hardly know how it is but I like these better than any other series of letters of hers that I have seen.” (Letter 34.) This material enabled Mrs Gaskell to create a Charlotte Brontë that rescued her from all the accusations of coarseness that contemporaries levelled at her. She is the daughter who survives everyone’s death, continues with fortitude, continues to put her father’s interests before her own, and she is a truly dutiful person.

But still there are moments in the collection where the writer surfaces. There’s one in particular which fascinates me, and which Mrs Gaskell didn’t quote from. She writes about waiting for a cheque from the publisher after the publication of Villette, the last novel she published. She had heard nothing, and actually planned to travel to London to find out what was happening, and how much she was going to be paid. In the end she didn’t need to, because it was published, but she received a cheque for £500, rather than the £700 she’d been expecting. Publication was delayed because Mrs Gaskell’s Ruth was coming out at that point (for the much larger payment of £2000).

But Gaskell doesn’t quote anything about money at all, because it would have been considered indelicate or coarse for a woman to be demanding a certain level of payment for her labour. Brontë does a typical “well I suppose it’s better than nothing” but clearly she knows it’s unfair.

She underlines “money transaction” at the beginning of the paragraph.

Money is something that was a constant worry for them. Her father was a totally selfmade man, who pushed himself through education and relied solely on the money from his living as a vicar, and they had to earn to survive. When their brother was alive, they had to earn to keep body and soul together. It’s just one of those moments where there’s a little eruption on the surface of anger and a sense of injustice. She’s not been fairly treated for the work that she’s done. The total she earned from her publishing was £1500 over her life, which, when you think of the work and how important it’s been in literary history, is staggering.

Women authors in the Victorian period trod a careful line between conventional, decorous femininity and asserting themselves as authors. The Brontë sisters published under male pen names (Charlotte’s was “Currer Bell”); their contemporary and Charlotte’s biographer Elizabeth Gaskell is still referred to as “Mrs” Gaskell.

Elizabeth Gaskell. 1851 portrait by George Richmond.

It’s striking how the letters feature Mrs Gaskell, and Harriet Martineau, and create a sense of Brontë in a literary network, but she always writes under her male pseudonym – she’s a step removed.

I think again she was very conflicted. She wanted to be seen as writer who spoke to other writers. She went to London and met Thackeray, whom she greatly admired, but then she would retreat. The friendship with Mrs Gaskell was different; it was constant and genuinely supportive. The friendship with Harriet Martineau, on the other hand, was very vexed; they fell out because Martineau saw Villette as extremely anti-Catholic. It’s another tension in Brontë that she wants to be seen as a writer and be part of a literary network, but actually temperamentally and socially finds that too painful, and withdraws back to the world of Howarth.

What was in her work that was viewed as “coarse”? Why did Gaskell feel she needed to reclaim her legacy?

Coarseness seems to be a kind of cover all term for passion, indecorousness, “unladylike” – so many people accused Jane Eyre of coarseness. It’s not that it’s vulgar, but that she speaks with a voice about herself. She refuses to accept a very narrow conception of what it means to be a woman. There’s a wonderful line where Jane says, ‘I’m not a bird, I will not be trapped, I have my own voice – If I marry you I will be your equal.” That’s pretty shocking, and many more conventional reviewers found that hard to deal with.

That’s why, in a sense, Mrs Gaskell felt a need to reclaim her reputation. For someone who presented herself to the world as a very conventional, dutiful person, Brontë’s work is extremely unconventional. Gaskell, as a fellow writer, she understood that, and was trying to smooth a path for Charlotte Brontë so that she wouldn’t be forgotten. It’s that complexity that makes her so compelling.

Thank you Suzanne!

Keep your eyes peeled for more Her Story posts over the coming months.

Interested in finding out more about women authors? The Fitzwilliam Museum will be exploring the world of Virginia Woolf this autumn in a upcoming exhibition.